August 1, 2023

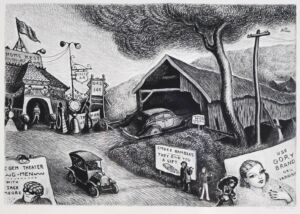

Progress, 1936. By Wanda Gág (1893-1946) Lithograph. 17.5″ x 20.5″

Wanda Gág (pronounced Gog) was born in New Ulm, Minnesota in 1893. She was the eldest of seven children born to Czech-immigrant parents. Both of her parents were artistic. Her father was a painter who decorated houses and churches, and her mother was a photographer. The Gág family home was built a year after Wanda’s birth, and it is said that her father decorated the dining room ceiling with a blue sky, white clouds, and cherubs. All the Gág children were encouraged to express themselves creatively, whether it was drawing, music, or dress-up. The family drew together around the table at dinner, and it seemed that creating art was a natural part of life.

Unfortunately, Wanda’s father died when she was fifteen. His last words were, in German, “What Papa couldn’t do, Wanda will have to finish.” Thus ended an idyllic childhood. Without his income, the Gag family went into deep financial poverty. Additionally, her mother’s health was failing. Without an adult to provide for the children, many in the community told Wanda to quit school and get a job. Wanda refused. Instead, she promised to see all her siblings through high school. She also pursued her own education and artistic career.

Wanda sold drawings to get through school. In her memoir, Growing Pains, she estimates earning more than $100 in the first eighteen months after her father died. She graduated in 1912 and taught at a country school for one year. She won a scholarship to the St. Paul School of Art, and later attended the Minneapolis School of Art. She moved to New York City in 1917, having won another scholarship to study at the Art Students League. While in NYC, Wanda painted fashion illustrations and other commercial work to send money back home. She was commissioned to illustrate her first book, “A Child’s Book of Folk-Lore-Mechanics of Written English” by Jean Sherwood Rankin.

This book was the beginning of many, but the troubles were not over for Wanda and her family. After her mother died, some community members in New Ulm wanted to divide the Gág children among foster families and an orphanage. So, Wanda sold the family house and moved the kids to Minneapolis. She gave each child a job: managing finances, getting food, obtaining clothes, and keeping the house.

Wanda became a full-time professional illustrator in 1919 and joined the Society of American Graphic Artists. In 1923, her youngest siblings finished high school, an enormous feat for a family of seven kids in the early 20th century. It was also the year of Wanda’s first solo show.

Wanda’s shows were successful, both monetarily and critically. After a few years, she made enough money to rent a three-acre farm in New Jersey called Tumble Timbers. At Tumble Timbers, Wanda began drawing on sandpaper. The rough, glittering texture of the medium suited her art style and subjects, which consisted primarily of everyday objects and landscapes. She loved drawing what was around her and the farm provided no shortage of inspiration and solace. Eventually, Wanda bought her own farm, called All Creation.

Wanda dove into her work, producing more than 100 editions of lithographs and woodprints. She also continued illustrating and writing children’s stories, publishing Millions of Cats in 1928. One year later, her work was shown at the Museum of Modern Art and the New York World’s Fair.

She created cover art and wrote articles for leftist magazines like The New Masses, The Liberator, and The Nation. Her criticisms of capitalism are demonstrated in this lithograph, “Progress.” She disliked the materialistic nature of the world around her and found commercialism distasteful, especially as the Great Depression trudged on.

In addition to her anti-capitalist beliefs, Wanda’s feminism was well-known. She shocked art school friends when saying she wouldn’t marry unless her husband ran the house while she had “drawing fits.” And while she had several long-term relationships and lovers, she didn’t marry until 1943, three years before her death.

Wanda stayed at All Creation until she passed away from lung cancer in 1946. She always supported her siblings, letting them stay with her and encouraging them to pursue their ambitions and talents. She became an internationally renowned artist for her illustrations, printmaking, and drawings. I hope she felt that she had fulfilled her father’s last words. That Wanda finished what her Papa could not.

Author Bio: Written by Summer Erickson, former Visitor Services Manager and Collections Assistant at Hennepin History Museum. Erickson graduated with a B.A. in Art History and Museum Studies from the University of St. Thomas in 2020. They cataloged HHM’s art collection in 2021. Erickson is currently working as a receptionist for MSS.

Bibliography

Abbe, Mary. “A Portrait of the Artist: illustrator Wanda Gag made her mark in a male-dominated era.” Star Tribune. March 11, 1993. Pages 1, 15.

https://startribune.newspapers.com/image/193121742/?terms=%22wanda%20gag%22&match=1

“Art in Focus: Wanda Gag.” Philadelphia Museum of Art. Accessed September 21,

Keaveny, Joan. “Life Story of Artist Wanda Gag.” Star Tribune. November 6, 1949. Page 9.

https://startribune.newspapers.com/image/181037439/?terms=%22wanda%20gag%22&match=1

L’Enfant, Julie. The Gág Family. Afton Historical Society Press, 2002, p.123

“Progress 1936.” Minneapolis Institute of Art. Accessed September 21,

Rankin, Jean Sherwood, 1856-, and Wanda Gág. Mechanics of Written English: a Drill In the Use of Caps

And Points Through the Rimes of Mother Goose. Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg Publishing House, 1917. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006536867

“Wanda Gag (1893-1946, American).” The Great Cat. Accessed September 21, 2021.

“Wanda Gag.” Smithsonian American Art Museum. Accessed September 21, 2021.

https://americanart.si.edu/artist/wanda-gag-1713

“Wanda Gag.” Wanda Gag House Historic Home and Museum. Accessed September 21, 2021.

http://www.wandagaghouse.org/gag-family-artists/wanda-gag/

Winnan, Audur H. Wanda Gág. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993, pp. 89.

This blog was made possible in part by the people of Minnesota through a grant funded by an appropriation to the Minnesota Historical Society from the Minnesota Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund. Any views, findings, opinions, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the State of Minnesota, the Minnesota Historical Society, or the Minnesota Historic Resources Advisory Committee.

This blog was made possible in part by the people of Minnesota through a grant funded by an appropriation to the Minnesota Historical Society from the Minnesota Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund. Any views, findings, opinions, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the State of Minnesota, the Minnesota Historical Society, or the Minnesota Historic Resources Advisory Committee.