October 6, 2021

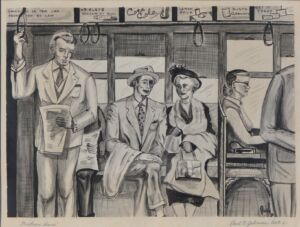

Street Car Scene by Paul Johnson

Public transportation is a vital part of many people’s lives. It creates less pollution, and the average cost for a year of public transport is cheaper than the cost of a car’s gas for a year. Many Minnesotans use the Light Rail or buses to commute to work in the cities. I bused from Blaine to St. Paul for three years because it was so cost-efficient. So how did public transit in Minnesota develop? How did it shape our cities and neighborhoods? And why is it not more extensive?

Let us start with a brief history of public transportation in Minnesota. The Twin City Rapid Transit Company, or TCRT, was created by Thomas Lowry in 1890. TCRT was a merging of the St. Paul City Railway Co. and the Minneapolis Street Railway, running a renowned intercity streetcar system from the 1890s to 1970. TCRT had a route system with hundreds of buses and electric streetcars, replacing horse-drawn cars. Streetcars became popular for their smooth ride on laid-down tracks, unlike buses or horsecars which bounced atop of what were often dirt or cobblestone roads. Streetcars were also helpful in the rough Minnesota winters, when snow buildup and icy streets could make riding in carriages or buggies even more uncomfortable.

This system of rails and scheduled rides changed the structure of cities and neighborhoods. In 1922, TCRT boasted 523 miles of track. People were no longer restricted to travelling within walking distance. Primarily white neighborhoods formed on the outskirts of the city, with residents taking the streetcar into the city for work. The streets once filled with pedestrians, playing children, and bicyclists, now included streetcar tracks and the occasional bus.

Automobiles were too new and expensive for most, and many residents actively protested the introduction of a fast machine that could cause injury to any walker in its way. While streetcars had a set path and speed, automobile drivers had no such restrictions. This resulted in many injuries and deaths to walkers, the majority of whom were elderly or children. The uproar regarding pedestrian safety was strong, and automobile manufacturers felt a loss of business. It was then that car manufacturers launched a campaign to switch the blame for auto accidents from drivers to walkers. This campaign popularized the word “jaywalker”, a derogatory term for someone who lived in the countryside or didn’t know how to behave in the city. The campaign was successful. It coincided with the introduction of the Model-T, a more affordable vehicle for the middle class, and was supported by new road laws that prevented people from walking in the streets as they once did.

Following the Great Depression and WWII, more people moved to the suburbs and bought private vehicles. The roads changed to provide more efficiency for personal vehicles rather than streetcars. Highways like 35W were constructed, displacing thousands of people. Highway 35W’s construction removed nearly 1,000 properties in South Minneapolis, which had been home to a thriving Black middle-class community. The highway wasn’t intended for their benefit, but for the benefit of drivers and the automobile industry that profited from them.

The end of streetcars in MN came soon after WWII. Streetcar lines became too expensive to operate for the low number of riders and TCRT focused on buses instead. Buses aren’t tied down to a rail and their routes can be altered to suit both the riders’ and company’s needs. On June 19, 1954, the last electric streetcar made a ceremonial trip through Minneapolis.

The Metropolitan Transit Commission, now known as the Metro Transit, was founded in 1967, and acquired TCRT three years later. Since then, Metro Transit has continued to put the emphasis on buses, with the addition of two light rail lines. However, its ridership has declined. In 2019, Metro Transit there were 77.9 million rides, as opposed to TCRT’s 226 million in 1922.

Aside from the increase in private vehicles, one reason public transit isn’t more extensive is a lack of funding. Many cities see public transit as a welfare program, not a public service that would benefit everyone. This means private companies that run bus lines rely on revenue for their growth and operation. While Metro Transit receives most of its funding from the Motor Vehicle State Tax and federal grants, its expenses are greater than its budget. This prevents the company from making upgrades to bus shelters, investing in green vehicles, and expanding its route system.

From the emergence of electric streetcars to the construction of the light rail, the Twin Cities have always relied on public transportation to get around. While we may not be taking full advantage of it now, hopefully the systems we have in place will grow to serve more communities.

Author Bio: Written by Summer Erickson, Visitor Services Manager and Collections Assistant at Hennepin History Museum. She graduated with a B.A. in Art History and Museum Studies from the University of St. Thomas in 2020. She is currently cataloguing and creating a digital exhibit of Hennepin History Museum’s art collection.

Bibliography

Burrows, Michael, Charlynn Burd, and Brian McKenzie. “Commuting by Public Transportation in the United States: 2019.” American Community Survey Reports. U.S. Census Bureau: April 2021. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2021/acs/acs-48.pdf

Carter, Jessica. “35W: Tracing Displacement and Data Collection.” University of Minnesota Heritage

Studies and Public History. January 5, 2021. https://umnhsph.home.blog/2021/01/05/35w-tracing-displacement-and-data-collection/#:~:text=Residents%20who%20lived%20along%20the%20path%20of%2035W,neighborhoods%2C%20and%20had%20their%20lives%20interrupted%2C%20or%20worse.

DeWitt, John. “The demise of the Twin Cities’ streetcar system.” Twin City’s Daily Planet. Jun 23, 2009. https://www.tcdailyplanet.net/demise-twin-cities-streetcar-system/

Ecklund, Eric. “65 Years Later: Twin Cities Streetcars.” Streets MN. June 19, 2019.

https://streets.mn/2019/06/19/65-years-later-twin-cities- streetcars/#:~:text=Burning%20a%20symbolic%20streetcar%20in%201954%2C%20preparing%20to,system%20in%20the%20Twin%20Cities%20shut%20down%20permanently

“Hennepin County Transit Improvements.” Hennepin.us. 2021. https://www.hennepin.us/transit

Kieffer, Stephen A. “Transit and the Twins.” Twin Cities Rapid Transit Company. 1958. p. 20.

Huynh, Kathleen. “Twin Cities Streetcars – The Rise and Fall.” Minnesota Digital Library. Accessed: August 28, 2021. https://www.mndigital.org/projects/primary-source-sets/twin-cities-streetcars-rise- and-fall

“Journey to work: Key results from the 2016 census.” The Daily. PDF. November 29, 2017.

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/171129/dq171129c-eng.htm

MacKechnie, Christopher. “Drive a Car?” Liveaboutdotcom. Updated January 7, 2019.

https://www.liveabout.com/public-transit-or-drive-cost-2798677

Melosi, Martin V. “The Automobile Shapes the City.” Automobile in American Life and Society.

http://www.autolife.umd.umich.edu/Environment/E_Casestudy/E_casestudy3.htm

“Metro Transit Facts.” MetroTransit.org. Metropolitan Council, 2021.

https://www.metrotransit.org/metro-transit-facts

Stromberg, Joseph. “The Forgotten history of how automakers invented the crime of “jaywalking”.” Vox.

Updated November 4, 2015. https://www.vox.com/2015/1/15/7551873/jaywalking-history

Stromberg, Joseph. “The real reason American public transportation is such as disaster.” Vox. Updated August 10, 2015. https://www.vox.com/2015/8/10/9118199/public-transportation-subway- buses

Thompson, Clive. “When Pedestrians Ruled the Streets.” Smithsonian Magazine. December 2014.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/when-pedestrians-ruled-streets-180953396/