March 31, 2022

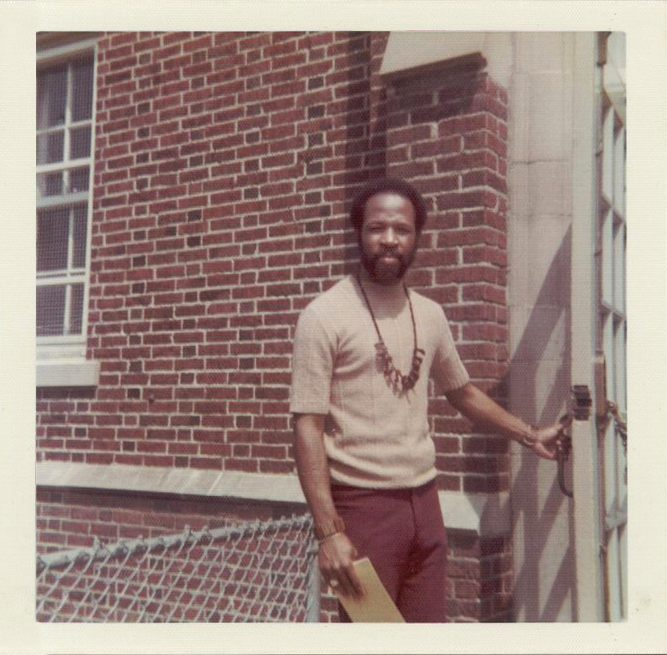

Mr. James (Mike) Andrews, Field Elementary School social science

teacher and woodshop teacher.

MOST PEOPLE CAN RECALL a teacher who made a difference in their lives, someone who treated them with respect and believed in them. For me and many others who attended Field Elementary School in South Minneapolis, that teacher was Mr. James (Mike) Andrews, a Black social science and woodshop teacher, who also coached at nearby McRae Park. He was known for his patience, high standards, and kindness. Field School continues to honor Mr. Andrews’s contributions by identifying an extraordinary eighth-grade student to receive the annual Mike Andrews Award.

Since I went to Hale Elementary School, a nearly all-white school, from kindergarten through fourth grade, “pairing” (which started when I was in fifth grade) offered me what my segregated neighborhood couldn’t — a chance to learn from teachers and students who neither looked like me nor shared the same life experience. I realize now how fortunate I was that Mr. Andrews was my teacher. As I reflect on my elementary school experience as a white student from a segregated community, I learned the value of inclusion by having teachers, school administrators, and friends who came from many different backgrounds. I enjoyed classes where we learned about diverse cultures, and I can’t imagine life today without the experiences made possible by attending Hale and Field Schools.

WHAT WAS HALE-FIELD PAIRING

Hale-Field Pairing was part of a Minneapolis Public School (MPS) pilot program that attempted to demonstrate it could desegregate Hale and ensure that Field’s students would receive the same educational resources as Hale students.

Prior to the pairing, 57% of Field students were Black and over 98% of Hale students were white.(1) Field was over-crowded, and the teacher-to-student ratio was extremely high. Hale was undercrowded and had a particularly low teacher-to-student ratio. Many Hale parents who resisted pairing claimed they were against busing and wanted a local school; however, at least 20% of Hale students were already being bused four times a day, to and from school and home for lunch and back. At the same time, no bus option was even available to Field students.

In the early 1950s, MPS invested in expanding Hale School, although enrollment plummeted shortly thereafter. Only portable classrooms were added to Field as it grew ever more overcrowded into the 1960s. (2) In effect, MPS refused to redraw school boundaries to more equitably fund and desegregate schools.

School board members and members of the community, including my mixed-race family, who supported school integration were publicly and privately threatened, harassed, and called out at school board meetings, in grocery stores, at churches, and more. The only African American school board member, Dr. Harry Davis, required police protection during the most contentious school board meeting on pairing in November 1970. (3) As noted by the Twin Cities Courier, a local African American newspaper, “perhaps we should commend the November 1970 school board meeting in its entirety including vulgarities. That date may mark the beginning of a citywide honesty, a subject we have swept under the rug too long.” (5)

The NAACP filed a lawsuit against MPS in 1972, charging that the district was in violation of the 14th Amendment in denying an equal educational opportunity to students by maintaining segregated schools. The lawsuit, Jeanette Booker v. Special School District No.1, outlined the many ways the district furthered segregated schools and challenged the district’s claims that school segregation was solely the result of discriminatory housing practices resulting from redlining and racial covenants. (4)

In fact, school boundaries reinforced segregated housing patterns, and schools were built to serve this housing pattern. For example, Field principal Brad Benson referred to Page Elementary School south of Minnehaha Parkway as “the doll house school” built to accommodate 320 children in a small segregated white enclave. Similarly, as racially mixed Central High School became undercrowded and predominantly white Washburn became over-crowded, Washburn parents resisted school boundary changes that would send their students to Central. They instead added portable classrooms to maintain Washburn as a white high school.

Although Hale and Field are separated by only 1½ miles (five minutes by car), the neighborhood parks and businesses were segregated by race. School pairing gave me an opportunity to build relationships and I began to experience what it means to live in a multicultural society and the impact racism has on it.

THE FIRST DAYS OF PAIRING

Pairing Hale and Field involved combining two communities of children, and some parents became school aides, beloved to many of us. The pairing required both communities to ride buses to school. Students from Field’s neighborhood were bused to attend Hale for kindergarten through third grade; Hale neighborhood kids were bused to attend Field for fourth through sixth grades.

Seventy percent of Hale School parents didn’t support pairing and that lack of support —and fears — peaked when fall arrived. Just before school started, some white people in our neighborhood started a rumor that the Black students at Field were going to beat me up. As I was waiting for the bus on the first day of school, a neighbor opened his front door and shouted, “You all think you can change us, you Commies!”

I was relieved to receive a warm welcome when I arrived at Field, and I enjoyed being introduced to the continuous progress curriculum. Students were divided into units; I was in the Green Unit with Mr. Andrews, Mrs. Neve, Mrs. Johnson, and Mr. Dornaden. Interviewing many of the adults involved in pairing, I learned from Karen Pratt, a Field school aide, that one Hale mother who insisted there would be “inevitable race riots” sat in the stairwell with her camera for the first few days of pairing.(6)

After a few weeks, during recess, my friends and I would sneak indoors to play Columbia and Motown 45s on the large portable turntable that looked like a suitcase. Pam Phiefer, Peter Sampson, and I got to act as news reporters speaking into the microphones in front of the entire unit. Due to federal funding for desegregating without court orders, our schools had technologically advanced equipment, which we were impressed by: reel-to-reel movie project-ors, headphones, microphones, and a 4-foot giant computer in the library also known as the Audio-Visual Center.

Our morning class schedule consisted of reading, writing, social studies, and math, along with a weekly rotation of science, art, gym, and woodshop. After lunch, for the remainder of the day we had “option classes” where students would decide which hobby, language, or skill area they wanted to experience. In woodshop, students worked with power tools, we powered light bulbs by hand, and I made a bright orange dashiki, which I enjoyed (while it fit!).

FIFTY YEARS LATER

Through the 2020 academic year, Hale-Field remained paired. Ironically, the population of both schools is now over 75% white. This is due in large part to predatory lending, to the history of the homes with racial covenants being in closer proximity to green space, leading to homes with rising property values, further exacerbating wealth inequality by race. Current community conversations aimed at reducing the number of racially isolated schools sound very similar to those from the early 1970s. I wonder today if students bused to a more racially mixed school would echo a Hale student’s response when asked what she thought of going to Field, “Well, I like it just fine, but my parents don’t want me to.” Not unlike me as a child, they might not understand why integration was needed. But as an adult, I’ve come to understand how policies, laws, and practices, including my own white privilege, promote racism and inequities. Growing up, I didn’t know the home I was raised in had a racial covenant saying only whites could buy the house. The pairing of Hale and Field was a small start to bridge the gap some pretend not to see. I hope today that white parents and students can embrace the gift of change and view integrated schools as an opportunity to move ourselves and our communities forward.

FOOTNOTES

- Greg Penny, “Field and Hale after three months, pairing of two elementary schools going smoothly. Minneapolis Tribune, December 19, 1971. p. 1B.

- Minneapolis Public Schools Rehabilitation for Field and Hale Schools: 1950 to 1959, School Building Fact Sheets for Field and Hale schools, Michigan State University, 1962, Hennepin County Library Special Collections.

- W. Harry Davis, phone interview with author, April 2, 2004.

- Booker V. Special School District No. 1, Minneapolis, et al., US District Court, District of Minnesota Fourth Division, p. 1.

- “As the editor sees it: That “School Pairing Trauma,” Twin Cities Courier, December 5, 1970, p. 6.

- Karen Pratt, phone interview with author, March 5, 2004.

Heidi Lynn Adelsman is a community historian writing on education, housing, and public health. She was on the committee that created the exhibit Separate Not Equal: The Hale-Field Pairing. She is a graduate of the University of Minnesota and Dunwoody College of Technology.

Separate Not Equal: The Hale-Field Pairing

On exhibit at Hennepin History Museum from April 28, 2022 through end of the year

This exhibit commemorates the 50th anniversary of the pairing of Hale and Field elementary schools in South Minneapolis. Yard signs announcing the exhibit and displaying a QR code linked to a special page on the Museum’s website were placed around South Minneapolis. Listen to audio segments exploring community efforts for desegregation, an important lawsuit against the district, the first day of school, and the innovative educational program introduced at the time of the Hale-Field pairing.