Steamboat on Lake Minnetonka.

Whether above the waves or below, the charm of the Minnehaha stays afloat.

By Elizabeth Vandam

Gordy Pederson, born in 1916, recalled “his small hand fit perfectly into his mother’s” while waiting at a dock on Lake Minnetonka to board the streetcar boat named Minnehaha. That was in the early 1920s and his memory of the experience was still vivid when he told the story to a local paper in 1994 nearly 70 years later.

“On summer days, the lake waters sparkled and it was a thrill to watch the bright yellow boat approaching and docking,” Pederson said. “A uniformed purser hopped onto the dock and secured the lines, then turned his attention to assisting passengers, collecting 10-cent fares and offering destination information. When Minnehaha sailed away, her shrill horn blew for all to hear.” He also remembered, in 1926, watching helplessly as the Minnehaha was scuttled. So when he found out that the streetcar boat had been salvaged in 1980 and was being restored, he “vowed to become involved.”

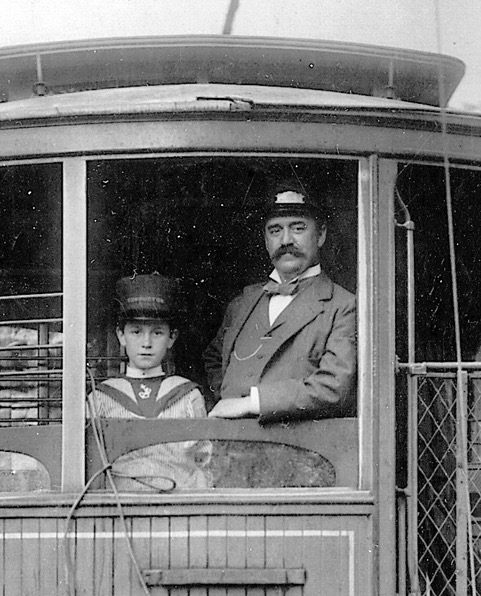

Calvin Goodrich, TCRT Vice President, and

son Donald, c. 1898. Photo credit Minnesota

Streetcar Museum.

BUILDING STREETCAR BOATS

Minnehaha‘s story began in 1905 with Calvin Goodrich, who was then the vice president of the Twin City Rapid Transit Co. (TCRT). Goodrich’s idea was a grand one: Streetcars from Minneapolis would bring passengers to Deephaven and Excelsior stations aboard bigger and faster cars on new tracks. Then, a fleet of steamboats would meet the streetcars for a transfer to service Lake Minnetonka. The Minneapolis Journal headline said it all: “Fast Ferries to Traverse Tonka For Trolley Co.” After traveling the country investigating passenger boat service on inland waters, Goodrich told the Minneapolis Tribune on September 30, 1905, “It did not take me long to find out that the boats now plying on Lake Minnetonka are among the best [built] in the country.”

So, not needing to cast a wide net for boat builders, the TCRT quickly chose Wayzata’s master boat builder Royal Moore and his Moore Boat Works to design and build a fleet of identical Express Boats. With a respected reputation, Moore had an enviable market share of boats on the lake already, including Goodrich’s Shawandasee. The Minnetonka Record announced the project to its readers in much detail on Nov 24, 1905: R. C. Moore… to draw plans for the new boats moulds and designs will then be taken to the company’s construction shops in Minneapolis… the work will be performed under Mr. Moore’s personal superintendence… Each of these [6] boats will be 70 feet long and 13 feet wide. They will have an average speed of 15 miles an hour… built with torpedo stern and will have two decks. The lower deck will be fitted with rows of wicker seats, very much like the standard streetcars, and the windows will be the same as those on the cars… The boats will seat from 125 to 50 passengers each each one will be able to carry the passengers of three cars. Stairs will lead aloft… the upper deck will be open on the sides and ends a canopy to protect passengers from weather. The finishing of the boats will be similar to that of the standard cars of the trolley company.” The boats were Minnesota-made, from design to construction materials to assembly. Surrounding forests supplied the white oak timber brought to Moore Boat Works. Craftsmen turned the timbers into curved, three-inch- thick ribs 68 for each hull’s framework. Materials then traveled for assembly to the TCRT’s Minneapolis streetcar barn complex. Boat builders assembled the hull; streetcar craftsmen built the cabins.

By May 1906, TCRT was ready to launch the fleet onto Lake Minnetonka: Como, Harriet, Hopkins, Minnehaha, Stillwater, and White Bear Lake. Using clever marketing, the boats were named for streetcar lines, painted the company’s canary yellow signature streetcar color, and featured an interior cabin design that ensured riders would immediately associate them with reliable streetcar transportation. No surprise that the name riders quickly adopted was streetcar boats. The boats operated May through September for 20 years – 1906 through 1926 – maintaining schedules that met arriving streetcar passengers at the Deephaven and/or Excelsior stations. The service was so efficient it accommodated more than 20 docks around Lake Minnetonka. The Express Boat service was advertised in Twin Cities newspapers as the “best” and riders (and readers) agreed. On weekends, visitors flocked to Lake Minnetonka for rides; on weekdays, the streetcar boats were filled with commuters.

Estimates reveal that by 1918, the Express Boats were serving about 200,000 passengers, but that’s when ridership began to decrease. World events such as World War I and the Spanish Influenza pandemic sent shockwaves of repercussions throughout the U.S., not to mention the increasing availability of automobiles. Car popularity influenced road improvements, which led to reduced public transportation ridership. Streetcar boats lost their riders, and eventually, so did their urban streetcar cousins. Following the lingering warmth of summer in September 1926, streetcar boat sisters Como, Minnehaha, and White Bear were towed by the tug Priscilla to deep water off Big Island. Their super-structures had been removed, their interiors auctioned. They were filled with tiles and bricks and their hatches were opened for a swift sinking. Over the next 54 years, their watery graves sat mostly undisturbed, except for curious divers on treasure-hunting adventures.

Boats on flatbed rail cradles were hauled from the Minneapolis streetcar

barn shop. Remaining upper decks and smokestacks were still to be

added. Before their trip by rail to Wayzata Bay for launching, each boat

received an inspection seal of approval from 25-year-old Everett Jones,

TCRT Operations Dept. inspector (pictured). Photo credit: Minnesota

Streetcar Museum.

DIVING FOR SUNKEN TREASURE

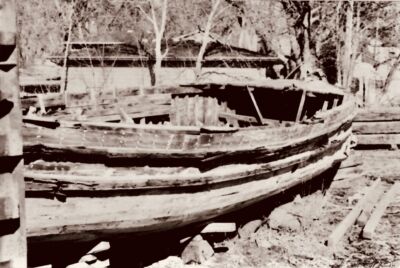

In July 1979, Jerry Provost, professional diver and Vietnam veteran, took a scheduled trip to Lake Minnetonka for equipment testing along with his dive team. Some months before, Provost had received a tip about the sighting of an outline of a sunken vessel near Big Island. Diving in the general vicinity of the tip, they discovered that their test site was directly atop what they came to believe was the Hopkins. (Following the 1926 scuttle of three streetcar boats, the Hopkins was sold, painted, and renamed Minnetonka. She remained active on Lake Minnetonka until her scuttle off Big Island in 1949.) Their suspicion was validated when Provost surfaced with a streetcar boat pilot’s wheel and a metal air scoop. Plans soon began to salvage the streetcar boat. Raising any vessel is no small feat, especially one that had been sunk for more than half a century. The project began Aug 25, 1980, with Provost managing a six-man professional dive team, supported by Bill Niccum’s Minnetonka Portable Dredge Company. Five days later, what was believed to be the Hopkins breached the surface. She was towed to Gideon’s Bay near Niccum’s shoreline office and floated on her own, appearing to show her audience that she was confident to begin her next life. Slowly, as the boat’s hull dried, her name appeared – Minnehaha. During the decade that followed, Minnehaha‘s future was the subject of multiple ownership transfers. First to lay claim was the Minnesota Attorney General’s Office. Next, the state decided ownership belonged to the Metropolitan Transit Commission (successor to the TRCT), who flatly declined the streetcar boat hull. Because the Minnehaha was deemed historically significant, the Excelsior-Lake Minnetonka Historical Society stepped in, requesting permission from the Lake Minnetonka Conservation District (LMCD) to re-sink her near the Excelsior Commons. That request was denied by the state. During this time, Provost admitted he and Bill Niccum, not having the resources to restore her, had also planned to re-sink the vessel in order to stop the deterioration she was suffering from exposure to the air. It was becoming obvious that the weather was destroying Minnehaha, doing more damage than the previous 54 years submerged. Her seams were coming apart from seasons of freezing, thawing, and plant growth.

The Minnehaha before restoration began.

SAVING THE MINNEHAHA AGAIN

The newspapers followed the story and enthusiasm increased to save Minnehaha. A bank account was opened for donations and discussions continued about locating her beside a lakeshore, but not in the water. Four years after her raising, in 1984, the Inland Marine Interpretative Center (IMIC) of Excelsior was created by Excelsior resident Darel Leipold. The center took ownership of Minnehaha with the intention of managing her restoration – the State of Minnesota said the organization would have five years to complete their project. But the IMIC was unable to support the project. Ultimately, Minnehaha‘s savior was Tonka Bay resident Leo Meloche, who convinced the MTM to take on the preservation project. Meloche knew MTM as an active preserver of Minnesota transportation history, having restored streetcars and trains. Meloche volunteered to direct restoration from beginning to end through MTM’s newly formed Steamboat Division. From 1990 to 1996, private citizens, corporations, and skilled craftspeople worked side by side, volunteering more than 85,000 hours. Fundraisers were held and donations of all kinds poured in, and original steamboat parts resurfaced – an anchor, a brass searchlight, interior seats, upper-deck benches, running lights, and more. * The Hennepin Co. Regional Railroad Authority allowed a barn (still used today) to be built on their property followed by the appearance of tools of all shapes and sizes An enormous trailer was designed to transport Minnehaha, pulled by a vintage Army tank hauler. Wood supplies came from discarded Douglas fir vats from Speas Vinegar Company, & Cypress pickle vats from Gedney Pickle Co. * All marine caulks, glues, adhesives, epoxies, s gloves, work apparel, brushes, sandpaper, paint rollers and more were donated from 3M. * O’Connor Engineering, whose owner Chadwell O’Connor built camera panners for Walt Disney, supplied Minnehaha with a “new in box,” never-used 1945 steam engine. * The Onan Corp of Minneapolis donated all power generation for Minnehaha. * Certified & licensed members of Minneapolis Steam Fitters Union & St. Paul Steam donated hours toward restoration. * Bob Dumas, who in a previous life rebuilt streetcars, recreated Minnehaha‘s superstructure & interior main cabin, right down to her rounded cabin & two- part windows mimicking the original vessel’s 1906 interior. * Viracon of Owatonna, Minn., donated all the shatter-resistant window glass. * Every person and company who volunteered and/or donated toward Minnehaha‘s restoration has earned deep gratitude. The complete list of names will fill a book, which is currently in the works. In 1995, in preparation for return to passenger service, Minnehaha completed its sea trials – also known as a watercraft testing phase – and recruited and trained crew for captain and purser roles. On May 25, 1996, 90 years after the first launching of the Express Boats on Wayzata Bay, Minnehaha celebrated her second maiden voyage. Purser Gordy Pederson – at that time the only living volunteer to have ridden and witnessed her demise as a youngster, and to have worked on her restoration – participated in her relaunch. Today, the streetcar boat Minnehaha continues to actively search for a new launch site and looks forward to returning to passenger service on Lake Minnetonka. Now owned by the newly formed Lake Minnetonka Historical Society (LMHS), the Minnehaha is well cared for by dedicated volunteers. Currently, Minnehaha is undergoing hull preservation, thanks to funding by a grant to LMHS – from the people of Minnesota through an appropriation to the Minnesota Historical Society from the Minnesota Arts & Cultural Heritage Fund. The Minnehaha exhibit at the Excelsior Museum is open to the public from May through September of 2024. For more information, contact the Lake Minnetonka Historical Society: lakeminnetonkahistory.org

The Minnehaha exhibit at the Excelsior

Museum is open to the public from

May through September of 2024.

For more information, contact the

Lake Minnetonka Historical Society:

lakeminnetonkahistory.org

Minnehaha on the lake.

ADDITIONAL READING

References in this story came from the following, which can be consulted for more information on the express boat history: Lake Minnetonka Historical Society Archives Minnesota Streetcar Museum Royal C. Moore, The Man Who Built the Streetcar Boats, Cherland-McCune Lori, 2013 Salvaged Memories, The Raising of the Minnehaha, Provost Jerry, 1996 The Little Yellow Fleet, A History of the Lake Minnetonka Streetcar Boats, Sayer Peterson, Eric, 1994. Twin Cities by Trolley, Diers, John W., Isaacs, Aaron, 2007