The Art-O-Graph story: Small, nimble firm has large, lasting legacy

By Paula M. Hirschoff

This article was originally published in Hennepin History, 2021, Vol. 80, No. 1.

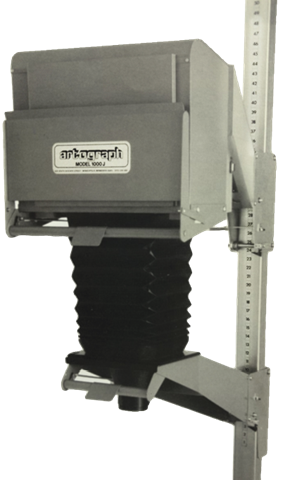

An early model of the Art-O-Graph, 1950s.

An assemblage of auto parts, a garage door track, a bellows, scrap iron and other junk yard remains: that’s how it began in the late 1940s. The entrepreneurs who pulled it together called their crude creation the Art-O-Graph. This machine, which projected an image directly onto a work surface, enlarging and reducing to scale, evolved into the first product of a Minneapolis company by that name that thrived for more than seven decades.

Small businesses are the lifeblood of the US economy, representing more than 40 percent of the gross national product in this country, but they demand tremendous effort. Small firms selling art products have faced especially challenging conditions: a fast-changing market, the digital revolution, the recession of 2008. Any one of these threats could have killed Art-O-Graph. Yet the firm endured, developing an international reputation for high-quality products and responsive customer service. How did it manage to succeed against all odds?

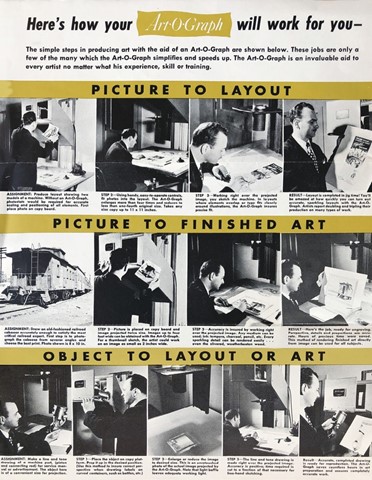

From the start, the founders, John Engel, Edwin Hirschoff, Les Kouba, and Seymour Peterson, set a goal of creating devices that save time. Several early inventions that first year were a flop. Then Kouba, a wildlife artist, articulated his need for a projector that enabled him to sketch from his photographs. With those recycled items mentioned above, the founders patched together the first Art-O-Graph (later known as Artograph), the only machine on the market then that could project an opaque image directly onto the drawing board right side up, enlarging and reducing as needed and saving the artist many tedious hours of tracing or scaling. This invention launched a long and ever-evolving line of products for artists.

Edwin Hirschoff (the father of this writer) took over as the first president and CEO and shepherded the firm through the rough early years. Born in Switzerland, Hirschoff emigrated to America in 1915 at age nine. Art photography became his passion, and cameras and darkroom technology, his expertise. He never had a chance to pursue higher education, but his creative drive carried him into a career in public relations and advertising and later contributed to the creation of Artograph. Years later, Paul Stormo, Artograph’s second CEO, described my father’s role. “[It’s] a slow tedious process [to build a business], but Ed stuck with it. In addition, he did a good job of marketing, presenting the product, and attracting customers. He was the ultimate entrepreneur — someone with great ideas that he wanted to promote,” Stormo said.

By 1953, meeting product demand meant producing up to 100 projectors at a time. Orders came from every state and many countries. Several were shipped to pre-Castro Cuba. During the 1950s and ’60s, Hirschoff devoted himself to building a network of dealers throughout the world and developing newer, sleeker models of the opaque projector. The company soon became a leader in the field of photogrammetry and graphic arts equipment with a reputation for top-of-the-line products. Customers were willing to pay a little more for Artograph projectors because they knew they would get better quality.

Art-O-Graph flyer’s step-by-step directions on how to use the projector.

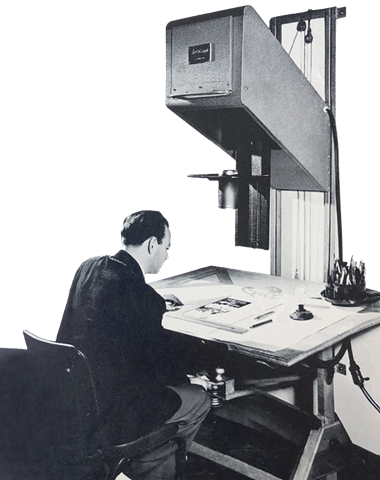

In the late 1950s, a client reported that he had adapted his Artograph for use in preparing maps, reducing his drafting time by 75 percent. Hirschoff seized on the idea. Redesigning the original projector, he came up with the Map-O-Graph. Updating old maps was a common application. An aerial photo was projected and enlarged to match the scale of a base map. New physical features, such as forests or streams, were traced from the projected images onto the base map. Thousands of Map-O-Graphs were sold in at least 60 countries. Customers included the National Geographic Society, the US Army Corps of Engineers, the National Space and Aeronautical Administration, which used its Map-O-Graph in mapping the moon, and scores of colleges and universities, which used theirs to teach mapping.

By the early ’60s, Artograph seemed like a member of our family. My mother, Marie Hirschoff, kept the company books, working from home while raising four children. I earned part of my college tuition working at Artograph headquarters in downtown Minneapolis (the Sexton Building at 529 South 7th Street) during summer vacation. The firm’s profit margins were limited in part by the need to contract the manufacture of machines to a sheet metal fabricator. In 1964, my father succeeded in procuring a loan from the Small Business Administration to establish a manufacturing plant. The firm became more profitable, enabling him to close his side business in commercial photography. Hirschoff dedicated himself wholeheartedly to building Artograph in part because he had loftier goals.

The projectors, for example, saved time so artists could be more creative. With the Map-O-Graph he aimed to join a global response to environmental challenges. In 1973 he wrote, “Environmentalists and ecologists are using the art of map making to help stem a rising tide of development and exploitation that threatens the very existence of the planet.” A booklet of case studies from 1973 described how the Resources Technology Corporation of Houston, under contract with the Environmental Protection Agency, was using its Map-O-Graph to measure US coastal zones and assess how they were changing over time. New products kept emerging in response to customer suggestions. Another innovative product was the StatMaker, which produced low-priced photostats (photocopies on special paper) for studio artists, expanding the firm’s clientele beyond the commercial art world.

Innovating continues

Edwin Hirschoff with a Map-O-Graph at an art materials convention in the late 1960s. The projector, adapted from an Art-O-Graph, was used in conservation, city planning, highway work, pollution control, and forestry.

When Hirschoff decided to retire, he launched a broad search for an appropriate candidate to purchase the firm. Paul Stormo, residing in Chicago at the time, replied to Hirschoff’s classified ad in the Minneapolis Sunday Tribune. Stormo had worked for Graco Corporation in Europe before founding an X-ray equipment manufacturing company. Though new to the art materials field, he had the qualities that my father was seeking. They hit it off and closed the deal in 1976. Hirschoff was not quite done, however. He had an idea for a revolutionary new projector that he had lacked the time to develop while managing Artograph. He stayed with the firm long enough to do so. The new smaller, less expensive tabletop projector called the DB300, could enlarge or shrink an image up to 18-fold onto the floor. It was a hit in the world of commercial art. Artograph Inc.’s sales volumes doubled in a year and tripled in two. Over the next 25 years, the firm sold 20,000 of the small opaque projector.

Affidavits affirmed the machine’s impact on commercial artists. “Before my Artograph, I was an average layout and graphic design artist. . . . I took two hours to do a drawing,” said Chuck McDougan of Missouri, “. . . but now with my Artograph I developed a competitive confidence and a craftsmanship accuracy.” Stormo hired Don Dow to manage sales and marketing, which my father had done previously. The firm moved from downtown to a suburban location on Vicksburg Lane in Plymouth, consolidating offices and manufacturing under one roof. Within a decade, Stormo emerged as a national leader in the field, serving as president of the National Art Material Trade Association in 1987–88. He foresaw that digital developments, including desktop publishing and computer graphics, would revolutionize commercial art. He urged retailers and manufacturers to take advantage of the impending technological and demographic changes.

In fact, Artograph Inc. was itself taking this advice. Over the next couple decades, the firm diversified, catering to new categories of clients, such as baby boomers seeking creative outlets upon retiring. Among its new products were light pads that illuminated film, X-rays, negatives, and artwork and “open studio” carts that amateur artists could easily carry to painting classes or plein air settings. The firm was innovative and competitive, traits necessary to the success of any small American business. Don Dow, Artograph’s third and last CEO, had a long history with the firm before he purchased Artograph when Stormo retired in the 1990s. As a boy, Dow had loved to sculpt and assemble objects. He taught art and did marketing for other art supply companies before joining Artograph, sharing office space with my father. They became good friends, and through the years, Dow honored him as “Father Artograph.”

Technologically adept and committed to the goal of helping artists be more creative, Dow steered Artograph further into the digital age. The swift spread of digitization had not been good news for the firm. But under Dow’s leadership, the company adapted, soon producing another success: the LED200, its first digital projector with which artists could reproduce digital images onto any surface with excellent image quality. The customer base grew broader, encompassing tattoo artists, scientific illustrators, forensic artists, wood carvers, metal sculptors, massage therapists, dollmakers, and designers of everything from trophies to monuments. Dow weathered the recession of 2008 with a loan. To reduce costs, he moved the firm west to the small town of Delano where he leased a building with offices for some 20 employees and a warehouse of 20,000 square feet.

“The value of being a small company is that we are nimble — we can fix it, we can change it, we can redesign it quickly. We are constantly evolving our products to meet the needs of the consumer,” Dow said in a spring 2013 interview in ShopArtMaterials. Annual sales revenue was $3.68 million in 2019, Dun and Bradstreet reported. That year, Dow retired, closing the Delano headquarters and selling the major product lines and all intellectual property rights to Studio Designs. This small Los Angeles firm anticipates that Artograph products will soon yield up to 25 percent of its revenues, featuring about 16 products, especially projectors and light pads.

Other brands of light pad are available, but the top pick in an online rating system in 2020 was the Artograph version. “The Lightpad 950 is the best lightpad you can find. This thing is the king of the hill or the Cadillac of lightpads,” remarked one online reviewer. At the time of the acquisition, Studio Designs president Scott Maynes said in a press release, “We are very excited to continue the legacy of the Artograph name.” He elaborated in a recent interview: “We knew that as far as opaque projectors were concerned, Artograph was the only game in town,” adding that its exemplary name extends to light pads as well as projectors. Sensitivity to client needs, ingenuity in adapting to challenges and changing times, and commitment to high quality — these were always integral to the Artograph reputation. They remain the greatest legacy of the small business that my father founded, as well as the hallmark of small business in the US — a vital component of the nation’s economic health.

Paula Hirschoff is a writer and editor born and raised in Minneapolis and now residing in Washington, DC. She has also written about her family’s immigration from Switzerland in two articles published in Hennepin History magazine: “An American story: Immigrant dreams deferred” and “Immigrant dreams realized: The life of Edwin C. Hirschoff.”

Down and Out: The Life and Death of Minneapolis’s Skid Row

by Edwin C. Hirschoff and Joseph Hart

In addition to founding Art-O-Graph, Edwin Hirschoff was a renowned photographer in the 1940s and ̕50s. He was a pictorialist, one who believed that photography was an art form. Hennepin History Museum holds hundreds of his photos and thousands of his negatives, many of which were used in this book on Minneapolis’s skid row, known as the Gateway District.

The Gateway District was a lively area consisting of dozens of bars, flophouses, pawnshops, burlesque houses, charity missions, and office buildings near the intersection of Hennepin, Washington, and Nicollet Avenues. The neighborhood was demolished between 1959 and 1963 as part of the first federally funded urban renewal project in America.

Edwin Hirschoff photographed the streets, buildings, parks, and rubble of the district’s demise. His photos, along with an essay by Joseph Hart, were published by University of Minnesota Press.

$26.95 paper, 2002, 116 pages, 54 b&w plates ISBN978-0-8166- 4054-6 upress.umn.edu