Spokesman for the Community: Cecil Newman and His Legacy of African American Journalism

by Iric Nathanson

This article was originally published in Hennepin History Magazine, Fall 2010, Vol. 69, No. 3

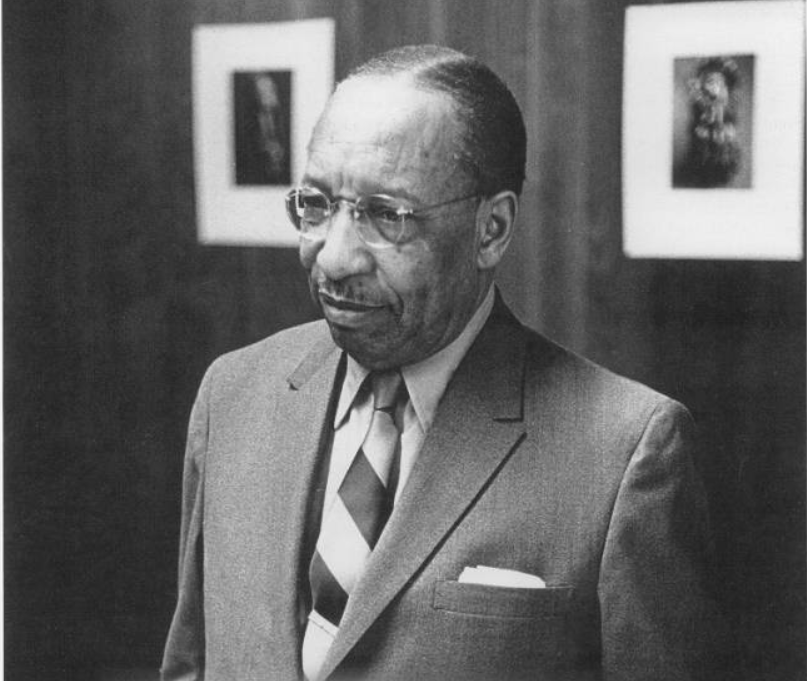

“Because we believe in Minnesota and its people and because we are convinced they will support an outspoken Negro organ, we are this week launching… the Minneapolis Spokesman, edited by Minneapolis people and devoted to the interests of the Minneapolis Negro.”¹ With that front-page declaration, a 31-year-old journalist named Cecil Newman unveiled the first edition of his weekly Minneapolis paper and its sister publication, the St. Paul Recorder, in August 1934. Known as the Minnesota Spokesman Recorder since the merger of the two community newspapers in 2000, the publication founded by Newman during the depths of the Great Depression has continued to chronicle life in local African American communities for more than 75 years. Today, Tracey Williams-Dillard, Newman’s granddaughter, is its publisher and chief executive officer.

Early years

In 1922, the Spokesman’s founder arrived in Minneapolis, fleeing a rigidly segregated Kansas City, Kansas, where he had spent his first 19 years. With only $1.57 in his pocket, the future newspaper publisher was determined to make a new life in the unfamiliar northern city where he had some family connections. The grandson of slaves, Newman had grown up in modest circumstances in a family that moved into the black middle class when his father got a job as a chef in a downtown Kansas City hotel. The young Newman may have had a relatively comfortable childhood, but even at an early age he had to endure verbal abuse from whites encountered on the street. “I do remember quite a number of times when a white adult would become abusive to me, such as ordering me to get out of his way with a rough ‘Step aside, nigger!’ I never reacted angrily on such occasions, feeling somewhat sorry for my tormenter,” Newman recalled.²

At the age of seven, he entered the local all-black segregated elementary school, only a block of away from the all-white school. The law mandated that the black schools be “separate but equal to the white,” but Newman remembers that only the “separate” was adhered to in pre-World War I Kansas City—not the “equal.” When the school board purchased new books, they went to the white school. Only when the books were out of date or in disrepair were they sent to the black school. At Newman’s elementary school, over-crowding and understaffing were persistent problems and class sizes were substantially larger than at the nearby white school. “Generally, I did not greatly resent this situation,” Newman later recalled. “It was a condition that existed, and I accepted it. I didn’t like it, of course, any more than I did the many other restrictions and impositions that were imposed on me by white people simply because I was black… I adjusted to it as child, though at times I had a great urge to change many things.”³ Newman continued in the segregated Kansas City schools through high school, becoming president of his senior class and a member of the junior Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC), while World War I was raging in Europe.

As a teenager, Newman, already an avid entrepreneur, initiated his newspaper career by taking on the distribution of three national African American publications in his hometown. At he same time, he participated in a work-study program helping to generate a small income for him as a student carpenter. “I had become a part-time carpenter, and a poor one at that,” Newman later recalled. “I had no interest in carpentry. It was boring in the extreme to me. While I was half-heartedly sawing boards in two and dejectedly hammering nails, I was thinking about working on a newspaper.”

“I would have been a very happy lad if I could have attended school part time and pursued a journalism career…Instead, my hands were busy with lumber while my thoughts were far away in a newspaper plant,” he noted.⁴ After arriving in Minneapolis, Newman worked at a variety of odd jobs while familiarizing himself with his new home and its community institutions. He soon learned that there were two African American newspapers in the Twin Cities, both of which had limited circulations. One, the Northwest Bulletin, offered him an opportunity to sell subscriptions and occasionally write copy. Those early articles were often heavily edited as he worked to polish his writing skills, but he was able to get a byline in the paper once his copy was accepted for publication. “This was a great morale booster,” he recalled. “To see my name in print, letting every reader know that I was the author of that article, really meant something to me. It gave me confidence; it was concrete evidence that I could gain entrance to the columns of the big-circulation newspapers. The pay was small in comparison to the value that the work was to me personally.”⁵

To support himself, Newman took a job as railroad porter for the Pullman Company, but he had set other career goals for himself. “By 1925, enough printers’ ink, by some strange kind of osmosis, seeped into my veins to condemn me forever after to a career in journalism. I couldn’t keep away from it, nor did I want to. That was where my thoughts were most of the time,” he noted, looking back at his early day in Minneapolis.⁶ Two years later, the aspiring newspaper man was ready for his first journalistic venture—a new paper known as the Twin City Herald, which he published in partnership with a local businessman who owned a print shop. Newman kept his job as a porter but spent as much time as he could editing the Herald: “When I wasn’t busy with portering, I was pecking out items on my typewriter.”⁷ Eventually, Newman’s partnership with the local printer raveled. He had gained valuable on-the-job experience as a newspaper editor, but his partner was running the venture into the ground as revenues declined and unpaid bills mounted up. Soon after Newman severed his connection with the Herald, it went out of business.

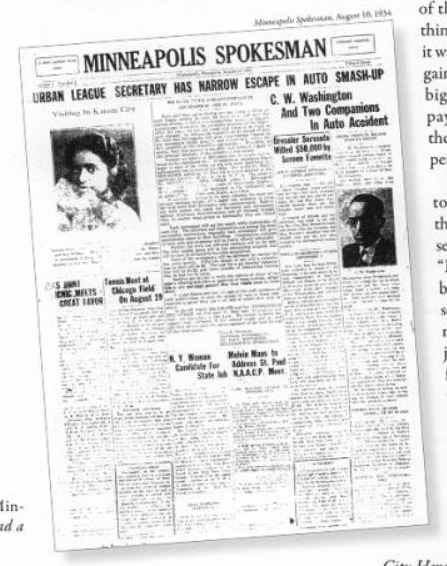

“I didn’t have enough money to begin one newspaper, so I began publishing two.” That’s how Newman explained his decision to found the Minneapolis Spokesman and the St. Paul Recorder.⁸ With an initial press run of 600, the Spokesman adopted a format that it continued to use through modern times. The front page covered the major news of the preceding week, with a lead article about a traffic accident involving an official of the Twin Cities Urban League. Newman’s editorial on page 2 commented on the dismal working conditions and low pay of blacks employed on government-funded construction projects along Mississippi River levees in the South.

The back pages of the Spokesman included one of its most popular features—the account of local social events in Twin Cities African American communities—events almost never reported in the mainstream dailies. In its first issue on page 4, under the heading “Woman’s World,” was the report of a picnic held by the Twin City Postal Alliance at Long Lake: “Despite the depression that has lessened the enjoyment of many, the attendance Sunday exceeded that of former years, and the government boys lived up fully to their established reputation as the Twin Cities’ best hosts,” read the Spokesman.⁹

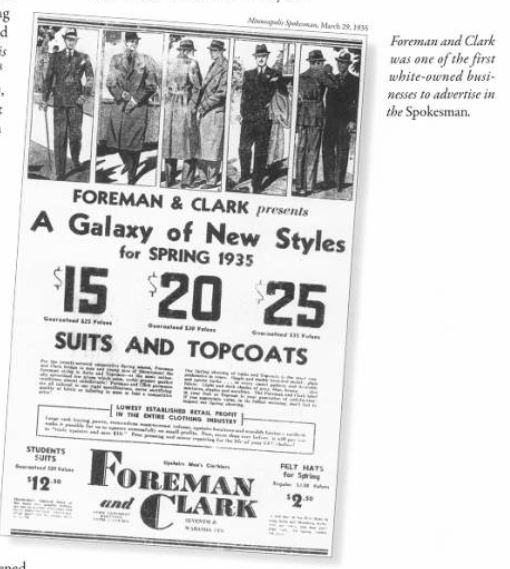

On the next page, the “Amateur Man about Two Towns” told it readers: “Mother Carver’s place on the Sixth Avenue North Road is still the gathering place for those in the know. Frank Hines tickles the ivories at the nite spot, and Tommy Lewis croons as only Tommy can.”¹⁰ The advertisers in that first issue were small African American-owned businesses—mainly tailor shops, recreation parlors, and funeral homes. Within a year, the Spokesman was attracting ads from white-owned businesses including Foreman and Clark Clothing Store, which continued its full-page ads in the paper for the next three years.

The new venture

“I didn’t have enough money to begin one newspaper, so I began publishing two.” That’s how Newman explained his decision to found the Minneapolis Spokesman and the St. Paul Recorder.⁸ With an initial press run of 600, the Spokesman adopted a format that it continued to use through modern times. The front page covered the major news of the preceding week, with a lead article about a traffic accident involving an official of the Twin Cities Urban League. Newman’s editorial on page 2 commented on the dismal working conditions and low pay of blacks employed on government-funded construction projects along Mississippi River levees in the South.

The back pages of the Spokesman included one of its most popular features—the account of local social events in Twin Cities African American communities—events almost never reported in the mainstream dailies. In its first issue on page 4, under the heading “Woman’s World,” was the report of a picnic held by the Twin City Postal Alliance at Long Lake: “Despite the depression that has lessened the enjoyment of many, the attendance Sunday exceeded that of former years, and the government boys lived up fully to their established reputation as the Twin Cities’ best hosts,” read the Spokesman.⁹

On the next page, the “Amateur Man about Two Towns” told it readers: “Mother Carver’s place on the Sixth Avenue North Road is still the gathering place for those in the know. Frank Hines tickles the ivories at the nite spot, and Tommy Lewis croons as only Tommy can.”¹⁰ The advertisers in that first issue were small African American-owned businesses—mainly tailor shops, recreation parlors, and funeral homes. Within a year, the Spokesman was attracting ads from white-owned businesses including Foreman and Clark Clothing Store, which continued its full-page ads in the paper for the next three years.

Early on, Newman made a concerted effort to market his paper to the broader community and its advertisers: “I decided in the beginning that if we were ever going to have better racial relations as a result of my newspaper efforts, I would have to reach white readers as well as black.”¹¹ When financial pressures mounted, as often they did during the Spokesman’s early years, Newman recognized that he needed support from white residents and their institutions to keep his paper afloat: “When things got too pressing, I would take time off and go soliciting subscriptions among the white people of the community. Often I would go downtown to stores that were glad to get the Negroes’ business but did little to solicit it.” “I would walk into the office of one of those leading citizens and ask him point blank what he knew about his Negro neighbors. The startled business usually replied that he had no Negro neighbors. Then I would tell him that one out every 10 Americans was a Negro and that quite a few of them lived right here in the Twin Cities. I would show him my paper very proudly, pointing out that most Negroes bought and read white papers; therefore white people should reciprocate and buy the Negro papers. It was quite an effective method. Usually, I would walk out of his office with a check for a year’s subscription.”¹² Through the 1930s, the Spokesman’s circulation grew steadily, exceeding 5,000 within a few years of its founding and reaching 7,000 by the early 1940s. In part, the burgeoning circulation was the result of yearly subscription sales in the broader white community.

Early on, Newman made a concerted effort to market his paper to the broader community and its advertisers: “I decided in the beginning that if we were ever going to have better racial relations as a result of my newspaper efforts, I would have to reach white readers as well as black.”¹¹ When financial pressures mounted, as often they did during the Spokesman’s early years, Newman recognized that he needed support from white residents and their institutions to keep his paper afloat: “When things got too pressing, I would take time off and go soliciting subscriptions among the white people of the community. Often I would go downtown to stores that were glad to get the Negroes’ business but did little to solicit it.” “I would walk into the office of one of those leading citizens and ask him point blank what he knew about his Negro neighbors. The startled business usually replied that he had no Negro neighbors. Then I would tell him that one out every 10 Americans was a Negro and that quite a few of them lived right here in the Twin Cities. I would show him my paper very proudly, pointing out that most Negroes bought and read white papers; therefore white people should reciprocate and buy the Negro papers. It was quite an effective method. Usually, I would walk out of his office with a check for a year’s subscription.”¹² Through the 1930s, the Spokesman’s circulation grew steadily, exceeding 5,000 within a few years of its founding and reaching 7,000 by the early 1940s. In part, the burgeoning circulation was the result of yearly subscription sales in the broader white community.

Battling discrimination

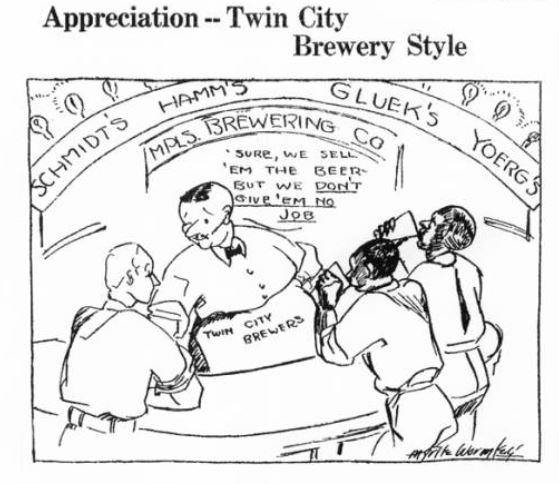

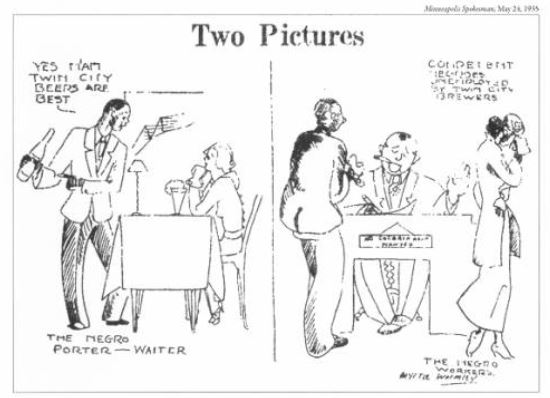

While Newman was busy soliciting subscriptions and advertising from the white establishment, he did not shy away from using the Spokesman to attack white-owned firms when he believed they were discriminating against blacks in their hiring and promotion policies. With the end of Prohibition in 1933, business was booming at the Twin Cities breweries, where hiring was underway even while unemployment locally and nationally was still in the double digits. But blacks were not benefiting from the hiring upswing.

In a May 10, 1935, front-page editorial titled “Is It Fair?” Newman criticized Twin Cities breweries for their failure to hire blacks, calling for a boycott of the local brewers until they changed their hiring practices. “When prohibition was repealed, it was thought that the reopening of employment in the brewing and distilling industry would be open in a larger measure to all American citizens, including the Negro. That this hope has not been realized in many localities may be illustrated by the fact that not a single brewery in Minneapolis or St. Paul has one of the Negro group in its employ,” the Spokesman editorialized. ¹³

Newman went on to question whether Twin Cities blacks should maintain their loyalty to locally produced beers when several out-of-town breweries did, in fact, employ blacks. “If the local brewers appreciate the patronage of our people, the least they could do [is] to give us a few jobs. There are several thousand men and women employed in these industries in the Twin Cities. There is absolutely no reason why, among that large group, there are no Negros employees.” ¹⁴

Newman urged the restaurants, bars, and nightclubs catering to blacks to prod local breweries to change their hiring practices. Should these efforts not be successful in “achieving justice for the Negro worker,” the Spokesman’s publisher urged “every beer drinker in the Twin Cities… to stop drinking beer manufactured by the offending breweries and drink those beverages brewed by firms that do not practice race discrimination in the selection of their employees.”

A month later, in June, the Newman reported on the impact of his earlier editorial. He announced that the planning committee for an Episcopal church picnic had canceled its order for six kegs of Hamm’s beer when committee members learned in the Spokesman that Hamm’s employed no Negro workers. Instead, the committee placed its beer order through a local beer distributor for out-of-town brands that agreed to put Negroes on its payroll. As local breweries began to feel the impact of the boycott, a delegation of brewery owners paid a call on Newman, offering him a $1,500 advertising contract. He turned them down flat: “If I had accepted that advertising offer, I would be admitting that I was a hypocrite of the first order. I would be advertising the boycotted products at the same time that the company manufacturing them were still denying employment to members of my race.”¹⁵

Later, the Spokesman used its news columns to crusade against racial discrimination in other areas of Twin Cities life. In January 1938, the paper’s lead story told of the University of Minnesota’s unwritten policy of excluding black students from university dormitories. By February 4, the Spokesman was able to report that the university had reversed course, due in part to the unfavorable publicity it had received. The U announced it would make dormitories available to all students, regardless of race.

That same year, the Spokesman spot-lighted the local black community’s effort to block the transfer of eight young black Minnesota members of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) to Missouri, where they were likely to face substantial racial prejudice. Again, publicity helped reverse a negative action—the Spokesman soon reported that the head of the local CCC camp had agreed not to transfer the eight men out of Minnesota. While Newman regularly used his news columns to spotlight problems and issues of concern to his community, he was always ready to relay good news when it occurred. In January 1937, the Spokesman reported on Joe Louis’s triumphant visit to Minnesota. The future heavyweight boxing champion was to met with Gov. Elmer Benson and address the state legislature. In May 1937, Newman announced that the Spokesman was prospering and that, as a result, it would increase in size. From the paper’s founding three years earlier, he had looked forward to the time when “public approval and support” would justify enlargement: “That time has come sooner that we had reason to expect.” Starting in the June issue, the paper would become full newspaper size with the addition of a seventh column on each page and a total of 114 additional inches of news copy and advertising.¹⁶

The war years and beyond

Through the early war years, as the nation geared up to fight the Axis powers, new employment opportunities in defense plants opened up for African Americans in Minnesota. In January 1943, the Spokesman relayed information from a Minneapolis Urban League report that “the number of Negroes, employed by local war plants continues to increase.” Firms hiring additional workers during the recent month included Minneapolis Honeywell, International Harvester, and D.W. Onan and Sons. ¹⁹

In late 1941, the Spokesman, like minority and mainstream publications across the country, expressed shock and dismay at the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the entrance of the United States into World War II. For Newman the war had personal impact when his son, Oscar, was inducted into the army in January 1943. In his editorial “War Gets Closer to Home,” Newman wrote: “No matter how much you ring the welkin for an all-out war effort, you never fully realize that we are at war until someone very close to you answers the country’s call…” He continued: “Now that our pride and joy is wearing a uniform, doing his best, we hope, for the greatest nation on earth, our personal approach to war and victory is no longer academic. The full personal shock of sending off a youth, who we can hardly believe is now a man, to the uncertainty of modern warfare, only comes when it touches your family.”¹⁷

Later that year, Newman again used his weekly editorial for some personal observations. On October 4, he had been lauded at a testimonial banquet in his honor: “Call it provincial if you will, but we have always said and felt that the people of the Twin Cities of Minnesota are the earth’s finest human beings,” the Spokesman’s publisher declared the next week, still basking in the glow of the interracial event attended by more than 500 of the Twin Cities’ leading citizens. “Proof of our conviction,” he continued, “was manifested for our special personal benefit at the testimonial banquet at the Nicollet Hotel. That so many busy people with so many important everyday tasks would plan, execute, and attend an affair for a humble fellow with obvious manifold shortcomings and small success is a tribute to the charity, patience, and kindness of people, black and white of all creeds, in our great state.”¹⁸

Newman played a direct role in furthering employment opportunities for his community when he became an emissary for Charles L. Horn, a Twin Cities industrialist who had built the massive Twin Cities Army Ammunitions Plant in New Brighton. Much to the chagrin of his personnel managers, Horn designated Newman to review and approve job applications from African Americans at the New Brighton plant. The two men developed a close professional and personal relationship that continued well into the postwar years. “[Horn] was the first mail subscriber to the Spokesman,” Newman noted. “His feeling of regard for the Negroes was genuine and deep-seated… his grandfather had [helped] slaves to escape from slave territory into free Iowa and hence northward to Canada, where they could live in freedom.” ²⁰

As the war was winding down in 1945, the Spokesman reported on a local political breakthrough—the election of Nellie Stone, an African American, to the Minneapolis Library Board. Stone was the first person of her race elected to public office in Minnesota’s largest city. Under the headline, “It Did Happen Here,” Newman observed: “When the voters of Minneapolis went to the polls on Monday and elected Nellie Stone to the city library board, they established a precedent unheard of in politics in a large metropolitan city. Of significance is the fact that although Mrs. Stone is of Negro ancestry, the city’s Negro voting population in only about 1 percent of the people eligible to vote. There must be hope for the unity of people when people from all walks of life here in Minneapolis…go to the polls and elect a Negro American woman to public office.”²¹

The 1945 municipal elections also brought another political milestone, the election of Hubert Humphrey as mayor of Minneapolis. Shortly after Humphrey’s election, Nell Dodson Russell, a Spokesman columnist, interviewed the mayor-elect and gave him high marks for his support of human rights: “In the matter of inter-race relations, Hubert Humphrey is sincere, frank and determined. [He] publicly expressed his opinions on the question of Negro rights long before he ever ran for public office. He is familiar with the problems Negroes face, and he is ready to help solve them, if he can get the cooperation he wants.”²²

In July, the Spokesman reported on Humphrey’s call, in his inaugural address, for the establishment of a local Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC). In January 1947, 18 months later, the Spokesman noted that Humphrey, backed by the city council, had followed through on his inaugural pledge to create on of the country’s first municipal FEPCs. Humphrey’s election as mayor marked the start of an alliance between Newman and Humphrey that continued as the most notable Minnesota politician of the era ascended to political height in Washington.

In August 1958, on the Spokesman’s 24th anniversary, Newman looked back at the paper’s early years: “Many readers of this paper remember its inauspicious beginning in 1934 with faith in the community and little else. They remember that the initial $55 investment was not enough [even to] pay the printing bill.” Newman went on to say that while his paper was dedicated to presenting the news, it also saw itself to presenting the news, it also saw itself as an advocate for “those things the Negro population needed but did not have.” He further observed: “Jobs, education, equal public accommodations, better housing, support of worthwhile community programs, end of discrimination of any type against the Negro or anyone else, was part and parcel of the paper’s early advocacy.”²³

For Newman, the 24th anniversary was particularly important because it coincided with the construction of the Spokesman’s new, modern office and publishing plant on Fourth Avenue South in Minneapolis. For some time, Newman had thought about building his own plant. Finally, in 1958, with the help of a construction fund generated by community members, he was able to achieve his long-sought goal. “There were approximately 150 Negroes newspapers being in published at this time,” he wrote later. “As far as I know, there was not a single one of them located in a new plant. Usually the publishers, lacking money, would find an old building where rent was cheap, and they would locate there. The equipment was generally meager. I determined that my plant was to be a new one, building and all. So the plans were made, and they materialized in due time. I was happy the residents of the area were pleased.”²⁴

As his building neared completion in October 1958, Newman declared in a front-page statement that “the erection of the handsome new home office and plant of the Spokesman and Recorder papers is the result of the fine support [that] this enterprise has received during the past 25 years from the Negro community of Minnesota in particular and the total community as well. This building is a small monument to the people who have faith in their fellow man and who have made Minnesota the great state that it is. We are very grateful and appreciative of the encouragement and support we have received.”²⁵

An emerging movement

Through the early 1960s, as an emerging national civil rights movement took shape, Newman and the Spokesman reported on its impact locally. In 1963, the paper sent its reporter to Washington to cover Martin Luther King’s triumphant march on Washington. On August 28, when the prolific Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. entrenched himself more deeply into immortality with his “I have a dream” speech, his words were of special significance for the committee of the Minnesota delegation: “For, as its members stood wearily in this vast sea of humanity with throats dry and eyes moistened, they were witnessing a dream come true.”²⁶

Five years later, the paper reported the assassination of King in Memphis, Tennessee: “Early in the Negro drive for the right of franchise and the end of discrimination in the south, we said the battle would cost the lives of some great and brave men,” Newman wrote. “Dr. Martin Luther King knew the perils from the day he brought leadership to the Montgomery bus boycott. He knew that any day he would be cut down by a sniper’s bullet or destroyed by a bomb.”²⁷

The Spokesman’s publisher went on to note the positive way in which many Twin Cities channeled their grief over the King assassination: “The march on Sunday of over 1,600 concerned white citizens through the Plymouth Avenue area in Minneapolis… was an exhibition of courage and brotherly love…It’s demonstrated what we have been saying in this space for years, namely that the the white people of these communities in general represent a tremendous fore for goodwill.” A year earlier, in summer 1967, the paper had reported on more troubling events in North Minneapolis. Black youths had torched neighborhood stores on Plymouth Avenue, many of which were owned by Jewish merchants.

In his editorial column, Newman expressed dismay at the disturbance: “The burning and looting that has gone on is regrettable and in our opinion will solve no problems…In fact [it] threatens the lives, property, and of more than any group, our Negro population,” he wrote. “In Minneapolis there has never been a time in the past 40 years when officials have not been approachable to those who wanted to present grievances in an orderly fashion. Until the peaceful demonstrations prove fruitless, no citizen should resort to jungle warfare tactics to gain attention to his demands. It is too costly and dangerous to our common communities.”²⁸

As the civil rights movement took on an increasingly militant tone, some in the local black community condemned Newman for what they saw as an outmoded stance and an eagerness to accommodate the white power structure. Friend and colleague Curtis Chivers later wrote: “With the growth of a new militancy among young blacks, Newman was sometimes called—to his face—an Uncle Tom. His reaction to this was neither indignation nor anger but rather a kind of compassionate amusement for critics who did not know or understand the forces [that] have brought about a climate in which Black militancy [could] function.” ²⁹

Newman acknowledged his critics’ charges but responded by noting that many whites as well as blacks face serious affronts and lack of opportunity—often because of their inferior economic position: “It was this kind of thinking things through on my part that made me a more rational human being. Many members of my own race never have been able to see my position on this point. They go only halfway, then stop and begin calling me names, ‘Uncle Tom’ being their favorite… I am definitely not an Uncle Tom. I just have my own viewpoint on the matter and a whole lot of faith in the inevitable outcome. The day is coming as surely as the sun rises tomorrow morning that, as Robert Burns wrote, ‘Man to man the world o’er shall brothers be.”³⁰

One era ends and another begins

On February 7, 1976, the Spokesman’s Cecil Newman died at the age of 72. He had been working full time at his office until he succumbed, unexpectedly, to a heart attack. At his funeral, more than 500 people crowded into St. Peters AME Church to hear Newman eulogized by his pastor, the Rev. E. Alexander Hawkins, as well as local sports figure Carl Eller and the U.S. senator from Minnesota, Hubert Humphrey. In a message to the Spokesman, Humphrey wrote, “With the passing of Cecil Newman, Minnesota has lost and outstanding and dedicated community leader, and I have lost one of my dearest friends…As publisher and editor of the Minneapolis Spokesman and the St. Paul Recorder, he demonstrated rare capability, compassion, and understanding. I don’t think there was any injustice or human need that escaped his attention.”³¹

Following his death, Newman’s family continued the work he had started 40 years earlier. In October Newman’s widow, Launa, became president of the Spokesman and Recorder newspapers.

In the early 1980s, the Spokesman chronicled the growing movements in Minnesota and elsewhere across the country to promote U.S. disinvestment from the racist white regime in South Africa. in 1984, the paper reported on bills sponsored by State Sen. Alan Spear and Rep. Randy Staten that would prevent the State Board of Investment from supporting corporations and banks doing business in South Africa. “Investment of Minnesota funds helps deprives 27 million people of their rights to free speech, vote, and personal choice, according to sponsoring groups such as the Catholic Commission on Social Development and Committee for the Liberation of Southern Africa,” the paper noted.³²

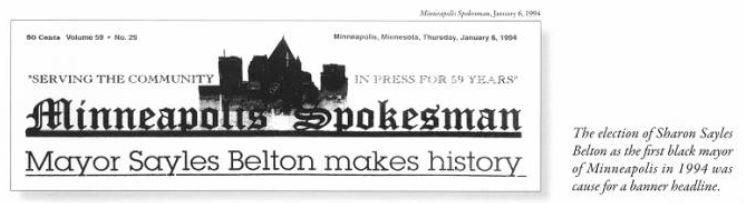

By the late 1980s, as affirmative action in employment gained momentum, help wanted ads prevailed in the Spokesman’s ad space. In January 1987, the paper advertised jobs for electronic assemblers, an accounting assistant, an insurance claims representative, and an inventory records specialists.³³ Later that year, the paper published a message from Minneapolis School Superintendent Richard Green. “The Minneapolis Public Schools have a moral and ethical commitment to desegregation/integration as a conditional for excellence in our schools,” Green maintained in a front-page editorial titled “Desegregation/Integration: The Challenge for our Community.”³⁴ Through the 1980s, the Spokesman maintained its focus on the news of concern to the local African American community while expanding its coverage of cultural affairs and entertainment in the Twin Cities area. During this period, Larry Fitzgerald became a familiar byline with his popular “Fitz Beat” column surveying the local sport scene. Later, Fitzgerald became a regular on the TV public affairs show Almanac. In 1994, the Spokesman celebrated the inauguration of Sharon Sayles Belton as Minneapolis’s first female and first African American mayor as she followed the path Nellie Stone Johnson had blazed nearly 50 years earlier. Sayles Belton’s husband, Steve, had grown up on Third Avenue South, just a block from the Spokesman office.

A new approach in the 21st century

At the start of a new millennium in January 2000, the paper unveiled its new name and new masthead—The Minnesota Spokesman Recorder. In a front-page editorial, the paper’s managing editor, Gayle Anderson, wrote, “Everything must change, nothing stays the same, the song goes. First and foremost, we have changed our name to the Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder, signifying the merger of the two papers we publish. Cecil Newman… is quoted in his biography as saying…’I didn’t have enough money to start one paper, so I started two.’ That quote could be reversed today to ‘We have too much news to report in two papers, so we have merged into one.'”³⁵ In 2006, Tracey Williams-Dillard, Cecil Newman’s granddaughter, took over management of her family’s newspaper as CEO of the Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder, just as the Internet and new media were battering the foundations of traditional print journalism. “Like papers everywhere, we are trying to adapt to new economic realities,” Williams-Dillard observed in a 2010 interview. “All of us in what some are calling the old media are having to climb a very steep hill in order to survive. The Internet is both a challenge and an opportunity for us.”³⁶

The Spokesman’s CEO explained that her paper is now online but that the print edition, with its paid advertising and its subscription fees, subsidizes the electronic version: “There are substantial costs for print that you don’t have online, but then online ‘only’ doesn’t generate the revenues needed to keep community journalism alive. It can’t be an either/or situation—either online or print—we have to use both. Our goal is to find a way that the Internet can contribute to our bottom line. The Internet can’t replace print media.” She continued, “We are not going to move away from our traditional focus on the African American community, but we need to broaden the focus to include new arrivals from other communities of color. Many of those communities face the same economic and social problems that African Americans have faced—discrimination, lack of employment opportunities, disparities in educational achievement. “We need to cover issues that affect these new communities directly. We want our new readers to say to themselves when they pick up our paper: ‘Yes, I can relate to that story, it deals with an issue that affect me, as well.'”

In the past, the Spokesman had social column reporting on community members’ parties and other social events. “We have gotten away from that now,” Williams-Dillard said. “We no longer cover Mrs. Smith’s coffee party and other personal events. That is something our readers are no longer interested in. They don’t know Mrs. Smith, so they really don’t want to read about her coffee party.” She continued: “At any earlier time, when the African American community was limited to a few specific neighborhoods in Minneapolis and St. Paul, there was a stronger network of personal relationships within the community, but that is no longer the case. Today, African Americans are widely disbursed through the Twin Cities area.”

“We can’t and we won’t move away from our focus on civil rights issues and other hard news,” Williams-Dillard added. “But we need to supplement the hard news with lighter features that can give people some relief from very difficult issues they read about on the front page every day. You have to write about the good things that are happening in the community so that you [keep] hope alive.”

References

- Minneapolis Spokesman, August 10, 1934

- L.E. Leipold, Cecil E. Newman, Newspaper Publisher (Minneapolis: T.S. Denison, 1969), 13

- Ibid., 17.

- Ibid., 32.

- Ibid., 51.

- Ibid., 55.

- Ibid., 64.

- Ibid., 71.

- Minneapolis Spokesman, August 10, 1934, p.4

- Ibid., 5.

- Leipold, 83

- Ibid., 87.

- Spokesman, May 10, 1935, p.1.

- Ibid.

- Leipold, 93

- Spokesman, May 28, 1937, p.1

- Ibid, February 5, 1943, p.2.

- Ibid, October 8, 1943, p.2.

- Ibid., January 8, 1943, p.1.

- Leipold, 93

- Spokesman, June 15, 1945, p.2.

- Ibid., July 25, 1945, p.2.

- Ibid., August 15, 1958, p.2.

- Leipold, 173.

- Spokesman, October 31, 1958, p.1.

- Ibid., September 5, 1963, p.1.

- Here and following paragraph, Spokesman, April 11, 1968, p. 2.

- Ibid., July 27, 1967, p. 2.

- Ibid., Feb 12, 1976, p.1.

- Leipold, 85.

- Spokesman, February 12, 1976, p. 1.

- Ibid., February 9, 1984, p. 1.

- Ibid., January 15, 1987, p. 7.

- Ibid., April 14, 1987, p. 1.

- Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder, January 6-12, 2000, p. 1

- Here and following, author’s interview with Tracey Williams-Dillard, February 25, 2010.

Iric Nathanson is a frequent contributor to Hennepin History and the author of Minneapolis in the Twentieth Century: The Growth of American City (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2009). He lives and works in Minneapolis.