Original stone carvings and stained-glass windows after restoration.

A raging fire can be the final blow to an aging building. The historic Oakland at 215 South 9th Street, now mostly encircled by surface parking, was ablaze on October 9, 2016, and the buildings future was never more uncertain. Demolition seemed all but inevitable.

Designed by master architect Harry Wild Jones in 1888 for builder William Burnett, the Oaklands building permit is dated June 20, 1889. The complex was scheduled to open for occupancy in September of that year. It is among Joness earliest known designs and his first multi-unit residential (apartment) commission.

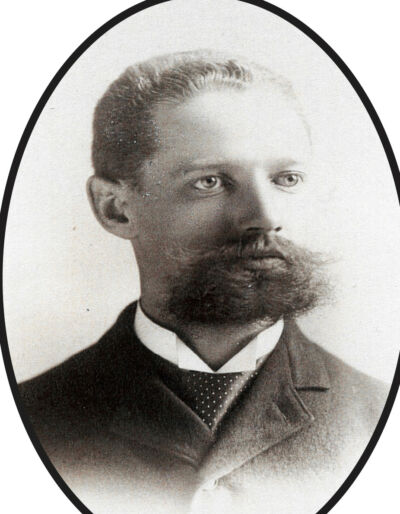

Harry Wild Jones, 1890

Jones attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, considered the countrys leading establishment of architectural instruction at the time. After graduation he began a year-long apprenticeship in Boston with architect Henry Hobson Richardson. A plum position for any new graduate, Jones said about his time at Richardsons firm, The time spent under the tutelage of this man, one of the greatest of modern architects, was of the highest value to me and his influence had much to do with molding my taste in my chosen art and profession.

In 1883 Jones moved to Minnesota. Eight years later, he was appointed the University of Minnesotas first official professor of architecture, restructuring the programs curriculum.

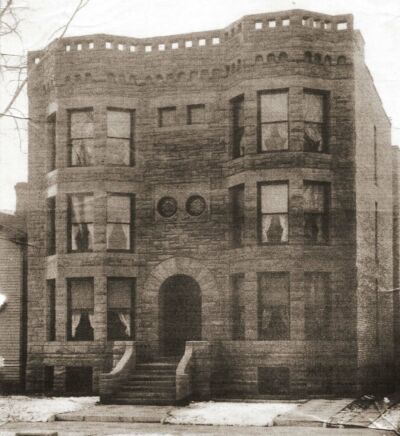

His firm was established in 1885 and was among the first occupants of the new Lumber Exchange Building in downtown Minneapolis. Joness modern apartment buildings were some of his firms earliest designs. With a nod to his first employer, he chose elements of Richardsonian Romanesque for the Oaklands faade heavy chiseled blocks of red limestone and semicircular arches framing the entrance and basement access. The structures most notable feature is above the arched doorway an inset element with circular stained glass windows and the Oaklands name, all surrounded by stone carving. Overall, the faade evokes the look and feel of a medieval castle with a drawbridge entrance, bracketed by rising towers and topped with a scalloped hem of masonry work.

When it opened, the Oakland was in an upper-middle-class neighborhood along South 9th Street toward the southeastern edge of downtown Minneapolis. A report about the Oakland in 1889 in a city newspaper stated the attention to detail, neatness, elegance and convenience has not an equal in the city. The six-luxury apartment units, two on each level, offered occupants a bounty of modern amenities of the day steam and hot air heat, an electric system independent to each unit, indoor plumbing, hardwood flooring with parquet insets, oak sideboards with beveled mirrors in the dining rooms, gas stoves, servant quarters, a rear freight elevator, and exterior covered porches. A full basement housed laundry equipment, the coal room, storage spaces for each unit, and an apartment for the person tasked with maintenance and janitorial services.

The Depression years ended the Oaklands splendid interior comforts. Its floor plan changed from six units to 24; bathrooms were shared, one for each gender per floor. Living conditions akin to a rooming house attracted less prosperous residents. By 1939, now called the Delta Hotel, advertisements read, clean, warm sleeping rooms, newly decorated, running water, maid and phone service starts at $3 week.

During the following decades, the building was renamed the Oakland and continued to be occupied. All the while, change was taking place. The residences and churches that started as the Oaklands neighbors were replaced by large hotels, then rooming houses, auto body shops, and finally surface parking shadowed by modern high rises.

The Oakland apartments, 1890. Jones is known to have designed over 200 structures in Minneapolis including Lakewood Cemetery Chapel, Lindsay Brothers Warehouse, Butler Brothers Warehouse (now Butler Square), Washburn Water Tower, and Lake Harriet’s restrooms.

A photo taken by Jones, inscribed in his hand, reads, The Oakland First Apartment Building in Minneapolis 1890. Today, the building is recognized as one of the citys first apartment complexes that has a common, central interior corridor. Its symmetri- cal faade and flat roof design were cost-effective for the day, and a central hallway was soon adopted as standard. This design was a marked transition from walk-up units, each with its own exterior entrance/exit door. In addition, the Oakland is a rare example of first-generation apartments in Minneapolis distinct for construction materials of brick and stone. Notably, three additional Jones designs of the genre exist in the city the Netacom (now called Cromwell Commons, 10 15th Street East) built in 1892; the Colonial (19th Street and Park Avenue) built in 1895; the Swinford (Hawthorne Avenue) built in 1897 and designated a Historic Landmark by the Minneapolis Heritage Preservation Commission in 1981. Joness firm is known to have designed 19 apartment buildings in Minneapolis. They earned the reputation of having been unchallenged in the Northwest for planning and building apartment houses.

Rising from the ashes The Oakland was condemned by the City of Minneapolis in December 2016, after the fire in October. Its owner since 1962 requested a demolition permit in early 2017. He was resigned that the building was unsafe, and demolition seemed the reasonable option. The permit was denied by the citys Community Planning and Economic Development department because of the Oaklands historic significance. The owner was encouraged to consider renovation or a buyer with rehab interest. In 2019, a private party who had renovation experience of historic properties and a passion for preservation negotiated the purchase of the Oakland.

The latest fire had devastated the buildings third level and roof. The buildings years of neglect were compounded by the water damage to extinguish the fire and three years of winter weather pouring in through the gaping roof hole. The seller had placed a zero dollar value on the buildings economic value. But the Oakland had retained its strong exterior features. That assessment was supported by Denis Gardner, National Register Historian for the Minnesota State Historic Preservation Office, when he toured the Oakland in May 2017. The new owner agreed with the historic significance of the building and went to work.

The interior stairway after October 2016 fire and three years of weather exposure.

Minneapolis City Council Member Lisa Goodman became aware of the Oaklands situation when the last fire occurred in October 2016, and the demolition permit request that followed. She and her staff were instrumental in the search for a new owner who could take on a preservation project, and then offered assistance at every step and through each hurdle. When asked how she became interested in preservation and why she felt the Oakland was a worthy restoration project, Goodmans answer stems from her years of experience involved with dozens of preservation projects throughout the city. Preservation is hard work she said, It requires a developer with deep pockets or an individual entrepreneur willing to put in the hard work through monumental challenges that come with an old building and meeting requirements of the current building codes. Minneapolis has lost too many historic buildings. The Oakland is one of the few remaining structures of its era and I couldnt sit by and watch another of these worthy buildings get demolished. Many structures in Minneapolis deserve to be preserved and we need more people to get that work done. People solve problems, not the government. We need more people who care. In the case of the Oakland, Minneapolis rallied around the building city officials, historians, and the public.

Protecting the Oakland with a new roof and gutting the interior were the priority. The existing roof was peeled away. Then workers removed one million tons of material, including decades of debris and some critters that had been living there rent-free. Dumpsters were filled with mold-covered walls and multiple layers of flaking paint and wallpaper (small samples were saved), broken window glass and framing, cast iron radiators, generations of wiring, plumbing and fixtures, furniture, and flooring varieties wood, linoleum, tile, carpet.

Emerging treasures were the excavators rewards. Six original tile hearths were uncovered where apartment fireplaces once stood. The tiles were cleaned, revealing a timeworn beauty. Salvaged wood flooring was reclaimed for interior walls and shelving, connecting the Oaklands past to its second life. Damaged brick and stone were repurposed for landscaping projects and interior work. Load-bearing supports in the basement remained sturdy so strong they were barely scarred by the insults of earlier fires a testament to Jones and all the craftspeople who put their hands and hearts to work in 1889.

Firmly anchored in the 21st century

The Facebook page Oaklands on 9th invited readers to the daily challenges and rewards of historic restoration. Workers posted photos of household items, coins, and long-lost toys. Visitors to the page responded with thoughtful comments, simultaneously curious and supportive of the undertaking. Stories and people from the buildings past surfaced. A gentleman who had lived at the Oakland as a boy, for example, shared his memories.

A newly remodeled room.

And donations flowed in. Eighteen chandeliers, a floor-to-ceiling mirror from the womens dressing room at Daytons, antique brass towel bars, and stained glass were donated by Facebook followers, along with framed artwork, some pieces specifically designed for the Oakland. The (Minneapolis) Grand Hotel donated their staircase and the spindles, rails, and treads were used to rebuild the Oaklands stairs. A GoFundMe account supported the restoration of original stained-glass windows that are among the buildings most notable features. Facebook postings prompted visitors to the jobsite, too. People often brought food for the work crew, which included volunteers assisting with everything from demolition through finish work of tiling and hardware installation.

The Oakland has experienced a comprehensive make-over. Surrounding business neighbors and curious passersby marvel at the transformation and pause to snap photos. The floor plan became twenty-four studio rooms, eight per floor. Hidden behind the eye-catching interior design are eco-friendly, efficient amenities. Plumbing, electrical, individual unit heating and cooling systems, walls, windows, and flooring support elegantly appointed spaces with chandelier lighting, upscale furnishings and bathroom tile designs, appliances, and quality internet service. The Oakland opened to short and long-term occupancy in 2021. The renovated environment is gracious and befitting of the Oaklands second century.

In October 2019, the State Historic Preservation Office recommended the Oakland for designation as a local landmark. The following month, the Minneapolis Heritage Preservation Commission made it official by bestowing that designation on the building. In summer 2022, the Oaklands restoration project will be celebrated by placing a historic marker at the front faade. The bronze marker is made possible with funds provided by the people of Minnesota through a grant appropriation to the Minnesota Historical Society from the Minnesota Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund and support from the Downtown Minneapolis Neighborhood Association. Bronze was specifically chosen for the marker because the metal is durable and develops a rich patina over time, much like the Oakland.

Perhaps the Oaklands most redeeming feature is its ability to survive.

Elizabeth Vandam, author of Harry Wild Jones, American Architect, The Door of Tangletown, A Reflection of Washburn Park, and co-author of Lake Minnetonka. She managed the project to secure the Oaklands marker and is a founding board member of the Lake Minnetonka Historical Society.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Oakland Apartments Designation Study Elizabeth A. Vandam, Harry Wild Jones: American Architect (Minneapolis, MN: Nodin Press, 2008). To make a reservation or for more information, visit oaklandson9th.com Visit the owners sister property in Loring Park, Minneapolis at 300clifton.com.