January 28, 2022

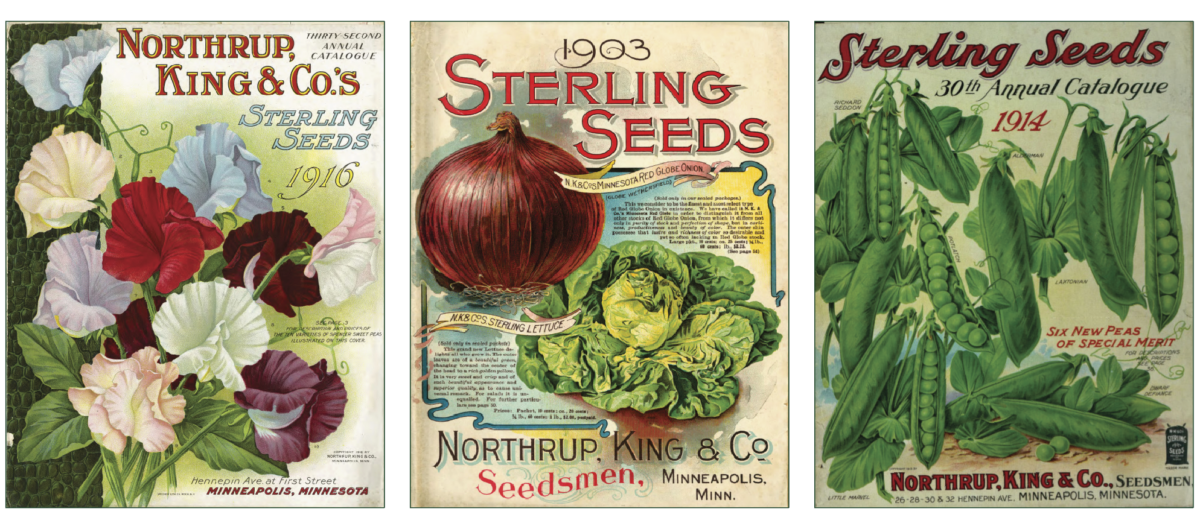

Seed Catalog. 1916. Courtesy University of Minnesota Libraries, Anderson Horticultural Library.

By William Burleson

Buildings aren’t often consigned to one purpose through their entire lives. Typically, buildings outlive their original businesses and are either replaced or repurposed. And every once in a while, a building not only survives, but it thrives in a new way, living not one but two extraordinary lives.

Nothing epitomizes this more than the Northup King Building.

Northrup, King & Company was for a time the largest seed company in the US, headquartered in an enormous building tucked away off Central Avenue just south of Broadway in Northeast Minneapolis. The vegetable and flower seeds are gone, but the 102-year-old structure now provides space to seed the creativity of over 350 artists and small businesses. It is the largest art complex in Minnesota.

The Northrup King Building didn’t survive because of its beautiful architecture – although, in some ways, the sheer muscularity and utility of the building has a certain beauty. It survived in part because of its size. But mostly, it survived because of the people with drive and a passion for the building and what it could mean for the neighborhood, for artists, and for art lovers.

Seeds for backyards and farmers alike

Thinking Minnesota would be just the place for tough plants, Jesse E. Northrup and Charles E. Braslan moved to Minneapolis from the east coast. “They believed in the hardiness, earthliness, and productivity of northern grown seed,” said Marca Woodhams in Biographies of American Seedsmen and Nurserymen. “They saw Minneapolis as a natural distributing point for a vast underdeveloped but promising agricultural region.” In 1884, they founded Northrup, Braslan and Company, located at Bridge Square on 1st Street and Hennepin Avenue. Their inaugural annual seed catalog came out in 1885.

Initially things did not go as planned. After several leadership changes and one bankruptcy, the business was reborn in 1886 as Northrup, King & Company. It continued to struggle, but by 1900, it had a reasonably booming mail order trade. Booming enough that in 1917, Northrup King built its huge new building at 1500 Jackson Street in Northeast. The building became the complex you see now, with 10 buildings along the railroad tracks with railroad spurs running to the length of the buildings’ loading docks. Nothing pretty here – this is the kind of complex that exists for one thing: getting things done. It was much like the entire neighborhood: blue-collar, gritty, and hardworking.

In 1950, the Minneapolis Tribune trumpeted Northrup King as the biggest “seed firm” in the US. “From its huge seed plant . . . seeds go out to every state in the union and to foreign countries.” Northrup King was famous for its seed packets sold to backyard farmers, boasting as many as 700 varieties of flowers and 400 of vegetables. Some machines at the factory could fill 700,000 seed packets per hour. But as late as the 1970s, seeds were also packed by hand.

Those iconic seed packs counted for only 10 percent of the company’s revenues in 1971; the other 90 percent came from farm seeds, such as hybrid corn. Northrup King was successful in fulfilling its founders’ dreams of developing hybrids that needed only short growing seasons and could withstand Minnesota weather.

But by the ‘70s, times were changing, and the clock was ticking for the hometown business leader, its workers, and the enormous building. In 1976, the business sold for roughly $194 million to Sandoz Pharmaceuticals, a conglomerate headquartered in Switzerland. Sandoz was a giant food, dye, agrichemical, and pharmaceutical concern, with 130 subsidiaries in 1984. Northrup King employed 2,800 people around the country.

Under the Swiss company’s leadership, by 1984 the company was looking to move. Sandoz wanted operations all on one floor for greater efficiency. Workers protested the closing with petitions and letter writing campaigns, to no avail. In 1986, Northrup King moved its operations and its 600 jobs from Minneapolis to Golden Valley. Jeff Farmer with the AFL-CIO, told the Minneapolis Star, “It’s not like they can claim economic hardship . . . There’s no reason this plant has to close.”

Minneapolis lost an iconic company, and Northeast had a giant abandoned building on their hands.

New growth

Painter Dean Trisko has a studio on the third floor of the Northrup King Building. Trisko is the quintessential working artist, as well as an art instructor at Minneapolis Community and Technical College. He’s had a studio in Northrup King since 2001. Before that he was nearby in the Thorp Building on Central Avenue.

“I grew up in the suburbs but started living in Minneapolis from college on. I chose Northeast . . . it was one of the cheaper areas to rent.” He and his family live about 12 blocks away from his studio.

When he first looked at a space in Northup King it was pretty rough, with the studio not even having heat. But in 2001, “It was already going quite well,” said Trisko. Now the main building has been divided into studio spaces and brought up to modern standards. Trisko credits this not only to the resiliency and tenacity of the artists the building supports, but also to Debbie Woodward.

Jim Stanton’s Shamrock Properties, a family business with properties all over the city, purchased the huge building in 1986. Stanton told the Journal in 2010, “My friend called me up and said, “Jimmy, how would you like to buy 780,000 square feet of building for $2.1 million?” Stanton snatched it up. Then he brought in his daughter, Debbie Woodward, to manage the property with a simple goal: fill the place with tenants.

“At that time, it was light industrial, office storage, that kind of thing,” said Trisko. Then, “[Debbie] got the idea of . . . renting to artists.” The main and largest building had a certain flexibility because of its vast open spaces. Woodward remodeled that building first, one section at a time, enclosing spaces to be studios, getting it up to code with heat, sprinklers, electrical, and yes, heat. “She didn’t rush the buildout.”

Woodward began to understand what artists needed, which was different from other businesses. She needed to strike that right balance between how much to improve the spaces and keeping the rents down. As a result, she kept the remodeling minimal and some of the history intact. Trisko’s studio has marks on the wood floors for seed bins and gouges for equipment being moved about. “Debbie Woodward went from trying to understand artists’ needs to becoming an advocate for artists and the arts,” according to Trisko. As a result, Northrup King has become the largest building of its kind in the state, if not the nation. “I would say Northrup King is the flagship of the Northeast Arts District,” added Trisko.

“The Northrup King Building is extremely important to the vibrancy and continued legacy of the arts in Northeast Minneapolis,” said Josh Blanc of the Northeast Minneapolis Arts District. The Arts District works with the city, businesses, nonprofits, neighborhood groups, and artists to collaborate and enhance the arts in Northeast. “There are many famous artists that have rented studios out of the Northrup King Building over the years. Steve Saks, Doug Argue, Randy Walker, to name a few. More artists are being developed every day.”

At the same time, the building never forgets its past. The entryway and stairwells are filled with historic photos of the iconic seed company, the building, and the workers who made it all happen.

The future of Northrup King

Buildings don’t have a say in how to weather change, put people do. Stanton died in 2017. And Debbie Woodward wanted to retire. She also wanted to protect what she had created in Northrup King.

According to Trisko, she had plenty of opportunity to sell the building. “She said there were people coming to her every four to six months to buy the building.” Trisko added, “I hear through the grapevine that she could have gotten more money from another developer, but she felt a certain obligation to maintain the artist nature of the building.”

Woodward decided to sell the complex to Artspace in 2019. Artspace’s mission is to create, foster, and preserve affordable and sustainable space for artists and arts organizations.

“All of us in the creative community were really worried about the future of the building complex when the owner, Jim Stanton, passed on,” said Kelley Lindquist, president of Artspace. “We are thrilled that now Artspace owns the Northup King complex,” he said. “We are not only maintaining the original space for working artists’ studios ‘as is,’ but also developing additional vacant buildings on the campus for future creative industries as well as for affordable artist housing.”

Artspace plans to renovate the vacant six-story Building 2 and the long, narrow, vacant two-story Buildings 3 and 8. These will become 84 units of housing as well as ancillary community-serving artist space. Eventually, the complex is expected to include performance spaces as well. And as current workspaces and future affordable artist housing open up, Artspace plans to reach out to many diverse communities in Northeast Minneapolis, such as the existing Ecuadorian and Somalian communities. “I think the Northup King Building has helped attract and keep artists in our state,” said Lindquist. “In good times and bad, it has been a consistent bright star in our greater creative community.”

Great buildings are constantly being reborn. You could say Northup King to this point has had two lives, and perhaps is now beginning its third with Artspace. Whereas for seven decades the building reflected the neighborhood with its sleeves-rolled-up, hard-working blue-collar grit, it now reflects – and leads – a new and more diverse neighborhood of artists and other creative individuals. Whatever lies ahead, it’s a good bet Northrup King will be in the mix, planting seeds for the generation to come.

William Burleson is an author and lifelong Minneapolis resident. He is the founder of Flexible Press,

Minneapolis. Learn more about him at williamburleson.com