Jumping the tracks, paying the freight

by Bill Beyer

This article was originally published in Hennepin History Magazine, 2022, Vol. 81, No. 3

Several railroads raced west from Minneapolis after the Civil War, slicing through St. Louis Park and Hopkins. In 1867, the northern route became James J. Hills Great Northern (now BNSF); two others, the Minneapolis and St. Louis (M&StL) and Milwaukee Road lines (1871 and 1881) ran side by side on a southern route.

In 1892, Thomas B. Walker envisioned an industrial suburb in St. Louis Park and built an electric streetcar line from Hennepin Avenue and Lake Street in Minneapolis between the northern and southern rail routes, along Minnetonka Boulevard and his newly platted Lake Street diagonal. He aimed streetcar traffic at the heart of his planned industrial/commercial center, located near todays Highway 7 and Louisiana Avenue interchange.

In 1887, the Interstate Commerce Act put all railroads under federal jurisdiction, making local governments powerless. Walker extended his streetcar from St. Louis Park into Hopkins in 1897 but was stymied short of downtown and the lucrative link to the resorts beyond on Lake Minnetonka: He could not get permission for a grade crossing of the M&StL freight rail line at 6th Street on Excelsior Avenue (now Main Street).

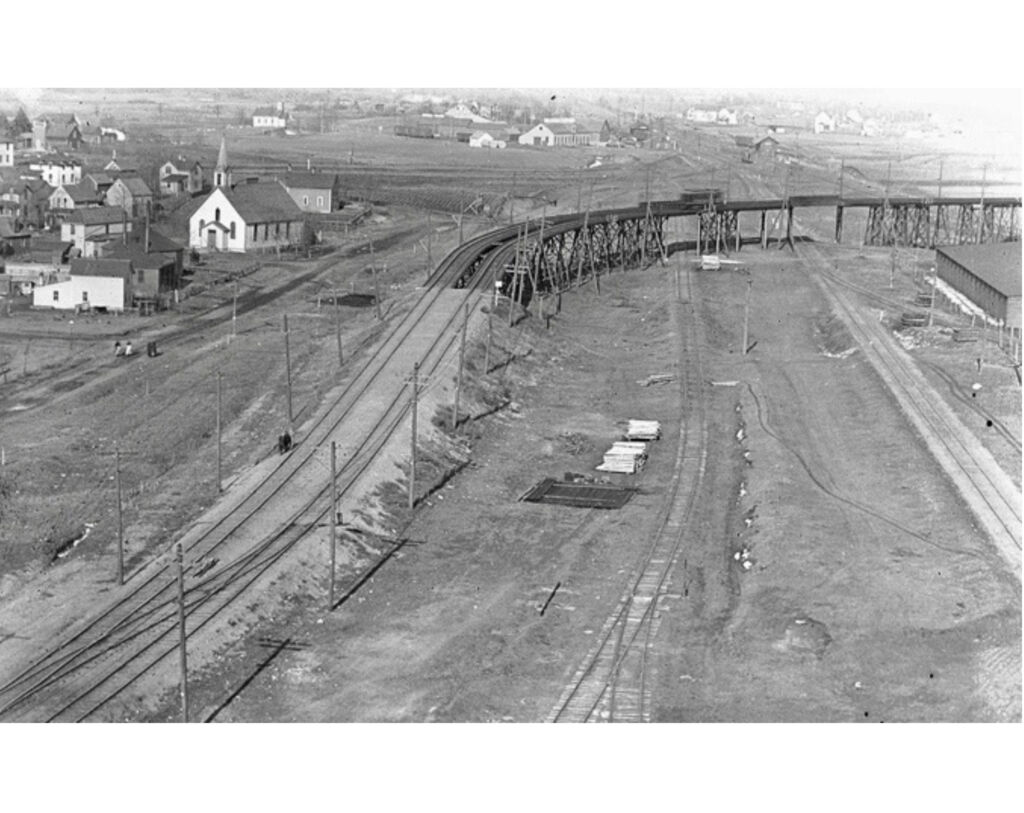

Streetcards and freight rail were grade-separated in 1905….. Courtesy of Minnesota Streetcar Museum.

Walkers streetcar line was purchased by Thomas Lowrys Twin Cities Rapid Transit Company and the stretch into Hopkins was abandoned in favor of a new southern route along the right-of-way of the defunct narrow-gauge Minneapolis Lyndale and Minnetonka Railway. This extended the Como-Harriet Streetcar Line west along 44th Street through largely undeveloped areas of Edina and Hopkins, past the Blake School. It jumped a new steel viaduct over multiple freight rail lines and rolled into downtown Hopkins and the lake resorts beyond in 1905. That elevated structure served until 1951.

Fast forward seven decades, and we have impending passenger rail service via Southwest light rail transit (SWLRT) connecting Minneapolis and St. Paul to the western suburbs once again. The old Milwaukee Road tracks are now owned by Canadian Pacific and handle a lot of freight traffic that has little incentive to play well with others at grade or at any other level. Their tracks have crossed busy Excelsior Boulevard in Hopkins for so many years that waiting for freight trains is simply a local ritual.

The steel viaduct over the tracks east of downtown. Courtesy of Minnesota Streetcar Museum.

But the SWLRT tracks run through

St. Louis Park on the wrong side of the freight lines and need to cross over to head south toward Eden Prairie. Therefore, another leap over the freight, and over Excelsior Boulevards 20,000 cars per day, is required.

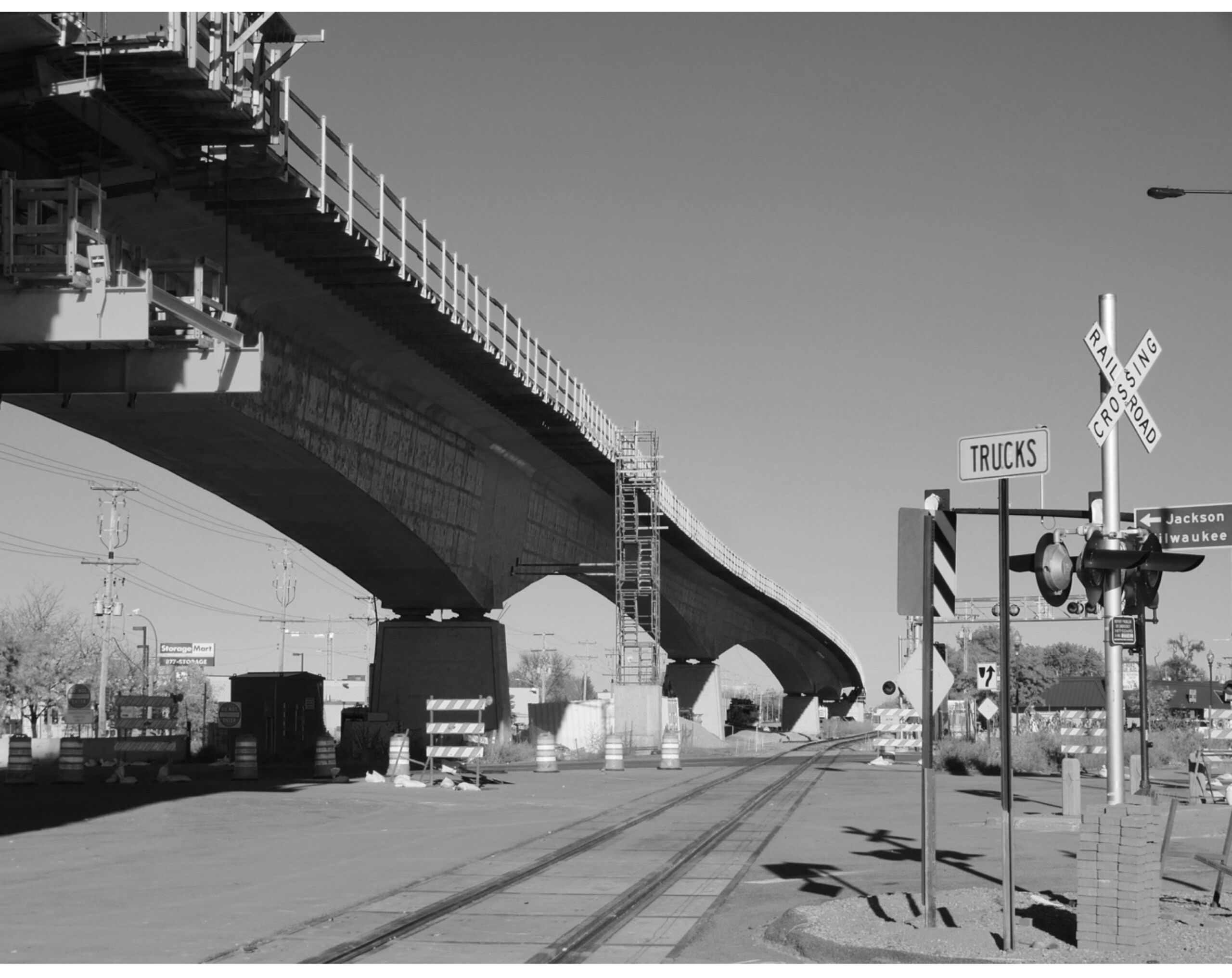

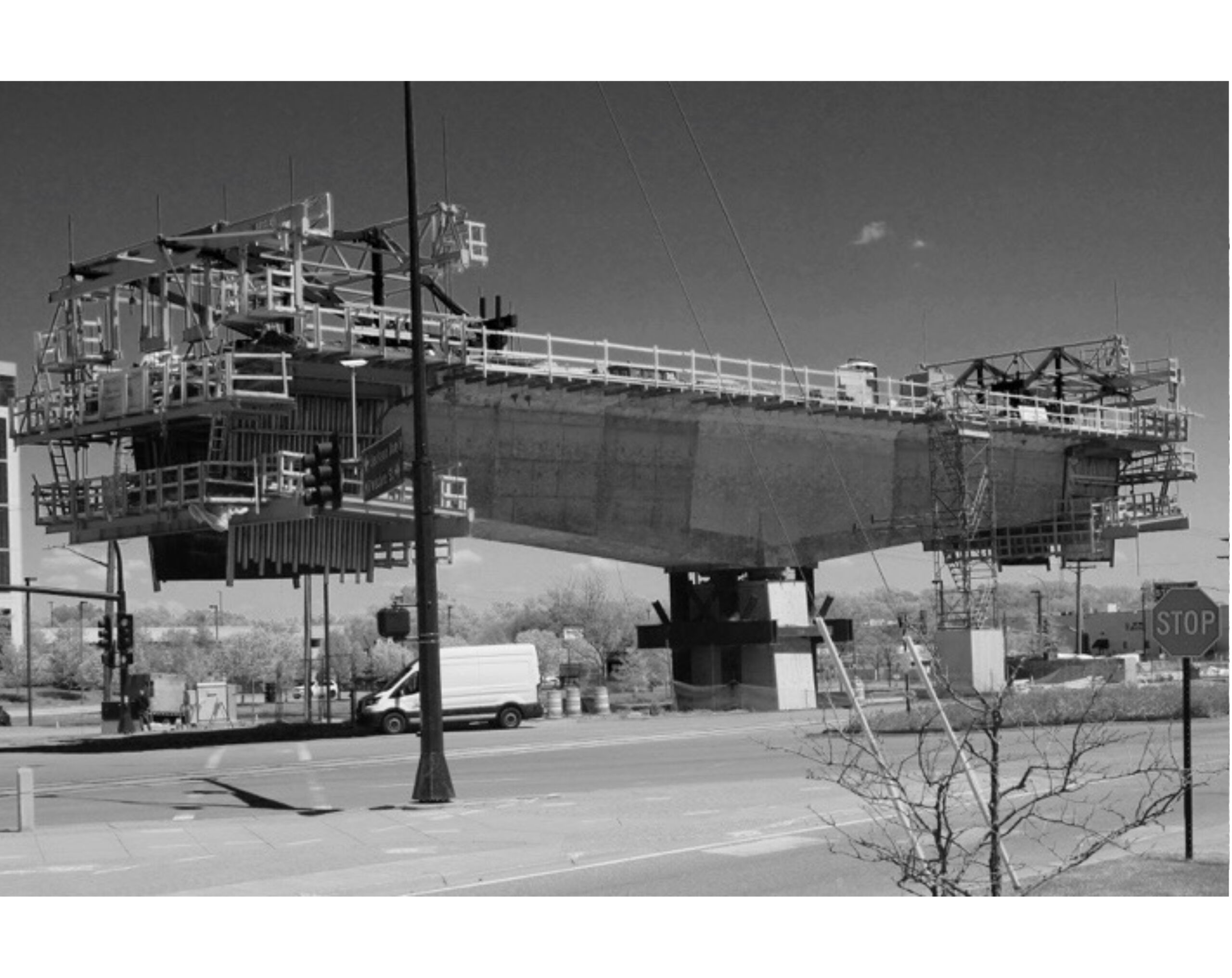

According to Metro Transits spokesperson Trevor Roy and engineering manager Jim Toulouse, the new post-tensioned, arched, segmental-concrete-box viaduct was designed to minimize impacts on both the busy county highway and the active freight line. To do that, and to accommodate the tight angle of approach parallel to the freight line, while avoiding a support pier in the middle of Excelsior, the graceful 1,620-foot-long structure needed long spans the longest at 400 feet. The difficulties of placing concrete during Minnesota winters plus the painstaking coordination required to schedule road closures and rail line outages have made progress appear glacial at times.

Glacial progress on the overall project was addressed in Minnesotas Office of the Legislative Auditor (OLA) report of September 2022, analyzing the reasons for extending the SWLRT project timeline by nine years to 2027 and doubling the original 2011 construction budget.

The OLA identified three causative factors, all related to the costs of colocation of LRT with freight rail, including a concrete barrier wall separating BNSF freight from LRT as it leaves downtown Minneapolis. Weve concluded the need for a barrier wall for safety, a BNSF spokesperson told the Star Tribune in 2017. At $82.6 million, the wall made a sizable dent in the projects contingency budget.

Oddly, Amtrak passenger trains, which run on freight company tracks, pass loaded freight trains between the Twin Cities and Chicago at differential speeds exceeding 100 miles per hour, wall-free and an arms length apart every day. Go figure.

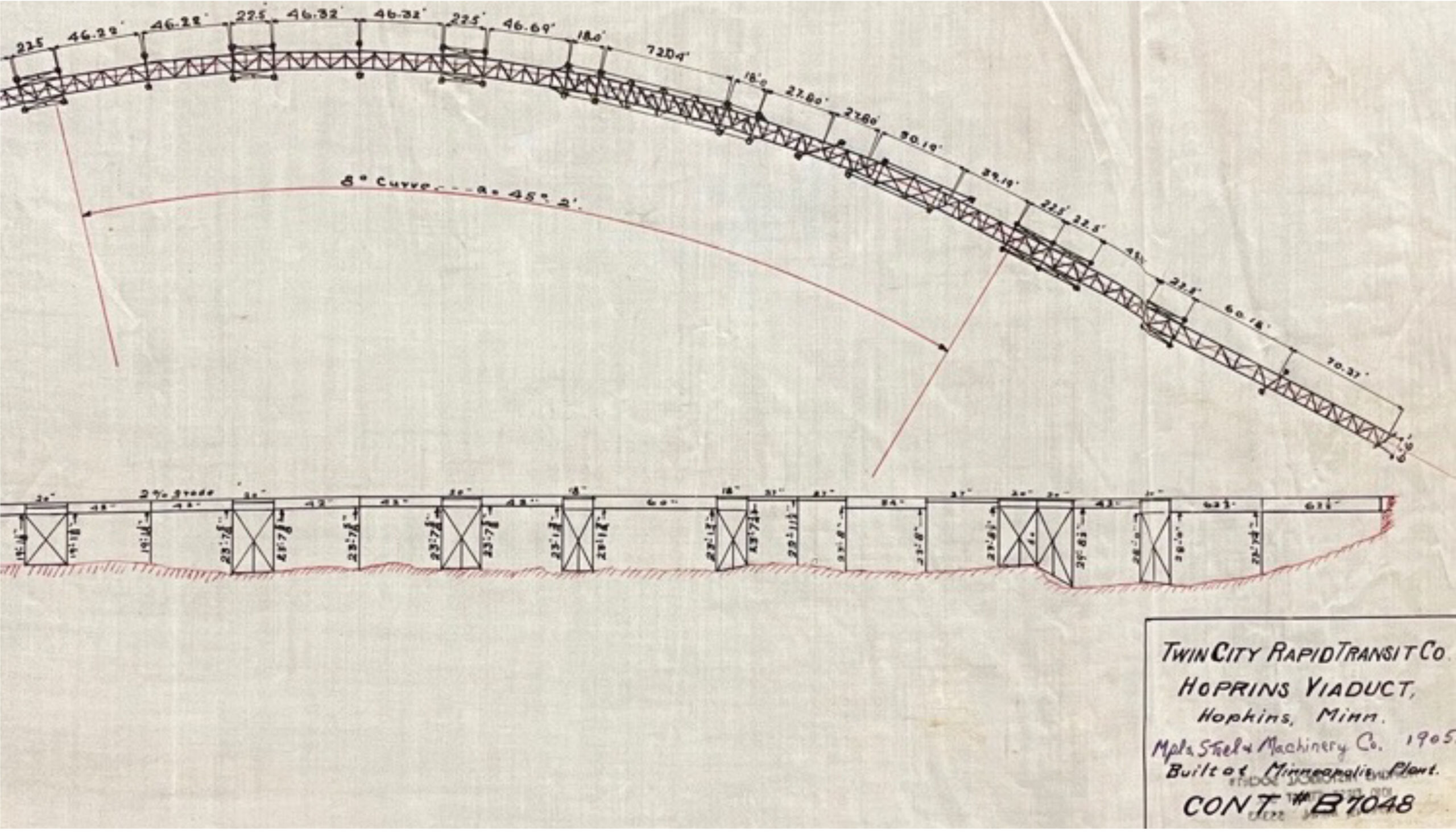

Engineer’s diagram of viaduct, 1905. Courtesy of Hopkins Historical Society.

Bill Beyer, FAIA, retired from the practice of architecture in 2019. He has served as president of AIA Minnesota, president of the Minnesota Architectural Foundation, as a regional director on the AIA national board, and has written more than 100 articles as a contributing editor for Architecture Minnesota magazine. He is a trustee of the St. Louis Park Historical Society and author of its book, Places in the Park: A Physical History of St. Louis Park, Minnesota.

At the news SWLRT viaduct over freight rail. Courtesy of author (Bill Beyer).

At the news SWLRT viaduct over freight rail. Courtesy of author (Bill Beyer).

At the news SWLRT viaduct over freight rail. Courtesy of author (Bill Beyer).