This article was originally published in Hennepin History Magazine, 2022, Vol. 81, No. 3

by Ames Sheldon

by Ames Sheldon

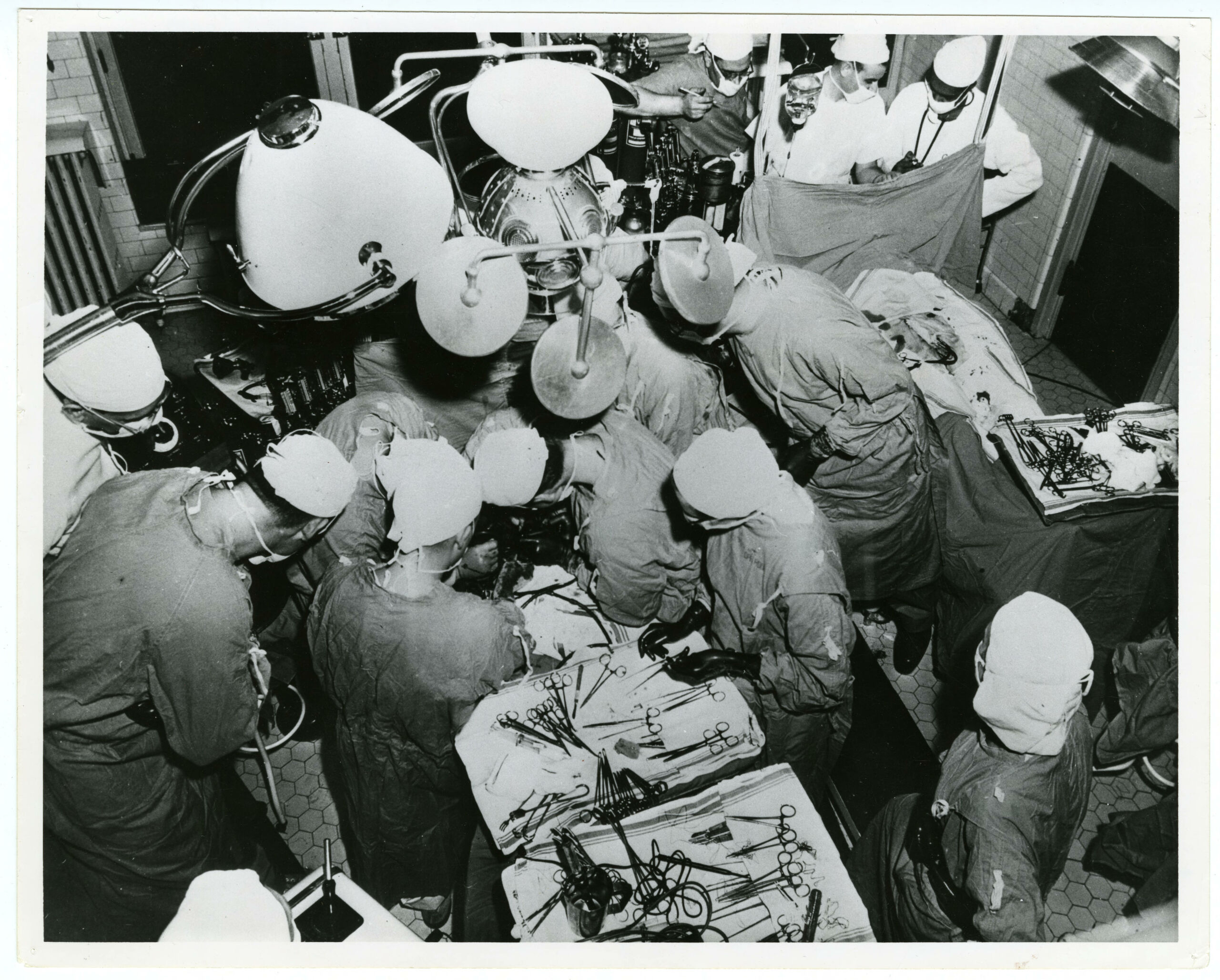

Remarkable advances in heart surgery were forged at the Variety Club Heart Hospital at the University of Minnesota during the 1950s. This is the hospital where Drs. F. John Lewis, Richard Varco, C. Walton Lillehei, and Mansur Taufic performed the world’s first successful open-heart surgery under direct vision, meaning they could actually, directly, see the organ they were working on.

Believe it or not, Minnesota has a famous Hollywood actor to thank for helping establish the first hospital in the United States devoted entirely to the diagnosis, treatment, research, and education for diseases of the heart — the Variety Club Heart Hospital.1

During World War I, while serving as a medical officer, Minneapolis physician Morse Shapiro was struck by the large number of soldiers with heart defects who reported having rheumatic fever during childhood. Rheumatic fever starts with the germ streptococcus, which causes tonsillitis, scarlet fever, inflammation of the ear, or strep throat.

After the war, Dr. Shapiro established a 40-bed hospital for children with rheumatic heart disease at the Lymanhurst Health Center in Minneapolis. As he examined children with heart disease, he also encountered many children with congenital heart defects.2 Dr. Shapiro’s clinic was later moved 25 miles away to the Glen Lake Tuberculosis Sanatorium to make room for Sister Elizabeth Kenny’s treatment of polio patients in Minneapolis.

Meanwhile, the University of Minnesota was receiving increasing numbers of children with rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease, but their facilities could not provide the extended periods of bed rest with medical treatment required for these cases. Many of these children from small towns and rural areas had to stay in local boarding houses in the neighborhood in order to visit the clinic as outpatients. Frequently, children were forced by poverty to return to their homes where they might remain bedridden for months with very little medical attention.

The Variety Club was chartered in 1928 by a group of theatre owners and showmen in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; they took their name from the title of the entertainment field’s trade paper, Variety.3 Al Steffes, a heart patient and friend of Dr. Shapiro’s, owned motion picture theaters in Minneapolis and he served as chief barker of Tent 12 of the Minneapolis unit of the Variety Club. In 1944 Steffes visited his friend’s rheumatic fever clinic and hospital. Recognizing the lack of facilities in Minneapolis for the treatment of children with rheumatic heart disease, and the difficulty of using a clinic in Minnetonka for teaching medical students, he invited Dr. Shapiro to make a proposal to the Variety Club. Dr. Shapiro described to the Variety Club the acute need for a special heart hospital in connection with the university hospital to serve the needs of children from the Upper Midwest. Club members responded with enthusiasm. In January 1945 the club made a formal offer to the university’s board of regents to raise at least $150,000 for the construction of a Variety Club Heart Hospital on campus; they also pledged to contribute a minimum of $25,000 annually for its support. The board of regents accepted the offer.

Meanwhile, President Harry Truman declared heart disease “our most challenging health problem.”4 More than 400,000 Americans died every year from heart disease. And 50,000 children were born in the US each year with heart defects.

During the 1940s the motion picture industry was at its height in this country. Every night of the week movie theaters were filled. Since many Variety Club members were involved in the industry, they decided to use the movies to make their fundraising appeal. Warner Brothers Studio created a short film in which actor Ronald Reagan appealed to movie audiences to join the battle against heart disease by contributing to the proposed hospital. By the end of the campaign, the Variety Club had raised more than $500,000 for the heart hospital, while the federal government provided $600,000 and the university contributed $400,000.

The Variety Club Heart Hospital was completed in March 1951 at a cost of $1.5 million. The new hospital encompassed a clinic on the first floor, 38 beds for adults on the second floor, 40 beds for children on the third floor, and a fourth floor where physicians conducted heart research. At the opening ceremony, actress Loretta Young joined University of Minnesota president James Morrill in cutting the ribbon.

With the end of World War II, medical school faculty who’d served in the war returned to the U of M’s medical school, and large numbers of young doctors who’d gone directly into the services from medical school returned to begin their residencies. As a result, the faculty had crowds of young physicians to train, and in 1945 the medical school was unusually well prepared to do so. Most of the departments were led by physicians still in their forties, at the peak of their energy, who’d established international reputations in their fields. Dr. Owen Wangensteen, head of the Department of Surgery, required each member of the surgical faculty to pursue some line of research, thereby creating an environment that fostered creative thinking. He also conducted a weekly review of complications that occurred during surgical operations, asking his physicians to be very critical in their appraisals of how and why mistakes were made and how they could be avoided in future.5

If only we could . . .

If only we could . . .

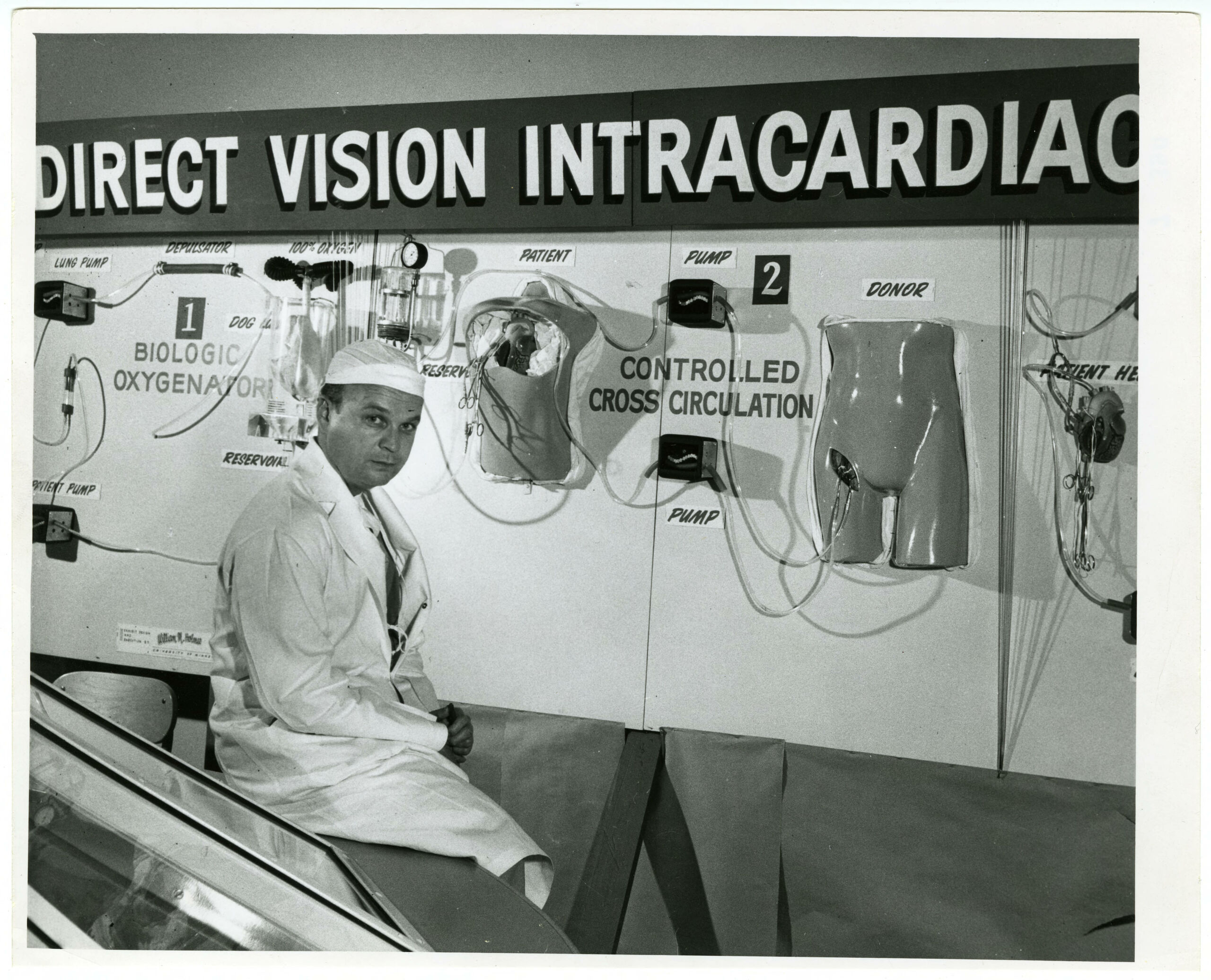

Years before, Dr. John Gibbon at Massachusetts General Hospital realized that patients wouldn’t die during heart surgery if the doctors could oxygenate the patient’s blood and maintain circulation during the brief period of a heart operation. In Minnesota in the late 1940s, Dr. Clarence Dennis took up the search for an effective heart-lung machine, but in 1951 when the Minnesota and Philadelphia groups each presented their results with mechanical blood oxygenators to the American Surgical Association, they had to admit they had not found an effective solution for maintaining sufficient oxygen in the blood during heart surgeries — far too many of the dogs they’d operated on died.

At the same time, surgical resident Dr. Walton Lillehei was conducting research on open-heart surgery at the University of Minnesota. According to G. Wayne Miller, author of King of Hearts: The True Story of the Maverick Who Pioneered Open-Heart Surgery, Dr. Lillehei “overflowed with unconventional new ideas.”6 In 1952, as he was conducting an autopsy of a deceased heart patient, Dr. Lillehei took the heart and stitched up the hole, commenting, “If only we could get inside the living heart.”7 The surgery itself was relatively simple, if only he could operate on the interior of the heart under direct vision. His goal was to find a safe way to slow down or stop the heart long enough to fix it, without depriving the body of the oxygen-filled blood it needs. Lowering the body temperature would reduce the oxygen requirements of the tissues, and in the lab Drs. John Lewis and Mansur Taufic had been experimenting with inducing hypothermia.

Jackie Johnson was born with a hole in between the upper chambers of her heart, a defect that kept her heart from developing normally. The five-year-old was small and sickly. On September 2, 1952, Drs. Lewis, Lillehei, Varco, and Taufic operated on her. It was the first successful open-heart procedure ever conducted under direct vision for the closure of an atrial septal defect.8 They reduced Jackie’s body temperature to 16 degrees below normal. At this temperature her circulation could be stopped for up to 15 minutes, which fully protected her brain from damage and was enough time to repair the defect. Jackie’s body temperature was reduced by immersing her in ice water in a watering tank, the type used on horse farms. One of the physicians noted that a horse watering tank was an unlikely addition to a modern operating room, but it worked. The surgeons opened Jackie’s chest and stopped the blood flow to her heart for five and one-half minutes while they closed an opening 2 centimeters in diameter in her atrial septum. She recovered and her heart murmur was gone. Thirty-five years later Dr. Lillehei invited Jackie back to the university to celebrate the anniversary of the first open-heart surgery in history to be performed under direct vision.

Heart-lung connections improve

However, it turned out that converting the heart back to a normal rhythm while it was still cold proved difficult. Under Dr. Lillehei’s direction, Dr. Morley Cohen began experimenting with cross-circulation using dogs. Then in March 1954 Dr. Lillehei hooked up the circulatory system of a one-year-old boy with a heart defect to that of his father, essentially using the father as

a heart-lung machine to keep his son alive while open-heart surgery was successfully performed. As the recent book The Open Heart Club by Gabriel Brownstein describes, the boy and his father lay on side-by-side operating tables with beer keg tubing connecting the boy’s circulatory system to his father’s, whose heart beat for both of them while the boy’s heart was repaired. This procedure doubled the risks of infection, brain damage, and death, making it an operation on a single patient that could result in a 200 percent mortality rate.9

At that time the American Heart Association named the University of Minnesota the “heart research center of the United States.”10 And according to the Journal of the Student American Medical Association, the U had the largest medical graduate training program of any university in the world.

In 1955 Dr. Lillehei conducted a successful open-heart surgery on an infant using a new version of a heart-lung machine invented by Dr. Richard DeWall under Dr. Lillehei’s direction. The “elegantly simple” DeWall/Lillehei bubble oxygenator had no moving parts; it was assembled from lengths of polyvinyl plastic food hose.11 Hundreds of other successful operations using this oxygenator followed. At that point the open-heart surgical programs at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis and at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester were the only places in the world where open-heart surgery was performed on a regular basis.12 The DeWall-Lillehei bubble oxygenator became the model used across the globe for open-heart surgery. A replica of their first oxygenator has been on display in the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian.

The next year, the university received a Cardiovascular Training Grant from the National Institutes of Health to fund a fellowship program to provide cardiovascular training of five to seven years leading to a master’s or PhD in surgery.13 Within one decade, 43 residents were trained through this grant and another 53 students (supported by other funds) received training through this program as well. In addition to completing laboratory research, residents joined Drs. Lillehei and Varco in clinical practice, where they learned to perform the methods developed for open-heart surgery.

Many of the talented heart surgeons who graduated from Dr. Lillehei’s residency program went on to develop heart surgery programs around the world. The most notable was Dr. Christiaan Barnard. After completing his surgical residency at the University of Minnesota in 1958, he returned to his academic home at the University of Cape Town in South Africa, where he performed that country’s first open-heart surgery the same year. In 1967 he performed the first successful heart transplant in the world. Other surgeons from Dr. Lillehei’s lab include Dr. Vincent Gott, who became chief of cardiothoracic surgery at Johns Hopkins University; Dr. Aldo Castenada, who became chief of cardiovascular surgery at Boston Children’s Hospital; and Dr. Richard DeWall, who became chair of surgery at Mount Sinai Hospital in Chicago.

Untethering the patient

Untethering the patient

The University of Minnesota’s heart surgeons dealt with various problems encountered during surgery. Sometimes patients would develop heart block — a condition where the heart beats too slowly because the electrical signals that tell the heart to contract are blocked. During one of Dr. Wangensteen’s seminars a physiologist, Dr. Jack Johnson, mentioned the Grass Stimulator that was used to stimulate and study the contraction of a frog’s leg muscles in physiology classes. It produced a small-voltage electrical charge. Dr. Johnson suggested such a charge would be an effective way to stimulate a patient’s heart when it was in complete heart block.14 This worked in 1957 on a child who developed complete heart block during surgery that Dr. Lillehei performed for a ventricular septal defect.

Dr. Lillehei attached electrodes directly to the heart of the patient with heart block, connecting wires to the heart muscle before suturing it up. Eventually, once the heart started beating on its own, he could gently pull the wires out and they would emerge. However, keeping a child tethered to a Grass Stimulator and to an electric outlet was untenable. “Many of these patients were kids,” said Dr. Lillehei. “They wanted to get out of their beds, but they couldn’t get any further than the cord. We had to string wires down the hall. . . . If they needed an X-ray or something that couldn’t be done in the room, you had to string them down the stairwells.”15

The Grass Stimulator was about the size of a portable typewriter and required an AC outlet as well as a 100-foot extension cord to move the patient from the operating room to the recovery room. In 1958 Dr. Lillehei asked an electrical engineer who assisted the surgical department, a man by the name of Earl Bakken, if he could miniaturize the Grass Stimulator. Two weeks later Bakken returned with a stimulator two times the size of a pack of playing cards.16 This pacemaker looked like a transistor radio. Powered by batteries, it could be adjusted to produce the heart rate desired, and it could be worn on the patient’s belt.

And this is the beginning of the story of Medtronic Company.

Ames Sheldon is the author of three award-winning historical novels: Eleanor’s Wars, Don’t Put the Boats Away, and Lemons in the Garden of Love. The character of Nat Sutton in Don’t Put the Boats Away is a heart surgeon at the University of Minnesota in the 1950s.

FOOTNOTES

1 Margaret Ayling Stanchfield, A History of the Variety Club Heart Hospital of the University of Minnesota Hospitals (University Archives), 1975.

2 Leonard G. Wilson, Medical Revolution in Minnesota: A History of the University of Minnesota Medical School (St. Paul: Midewiwin Press, 1989).

3 A History of the Variety Club Hospital.

4 Harry S. Truman, “Statement by the President on the Increasing Incidence of Heart Disease,” February 8, 1947,

presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/statement-the-president-the-increasing-incidence-heart-disease.

5 Medical Revolution in Minnesota.

6 G. Wayne Miller, King of Hearts: The True Story of the Maverick Who Pioneered Open Heart Surgery (New York, NY: Times Books, Random House, 2000).

7 Ibid.

8 Medical Revolution in Minnesota.

9 Gabriel Brownstein, The Open Heart Club: A Story about Birth and Death and Cardiac Surgery (New York, NY: Public Affairs, Hachette Book Group, 2019).

10 Journal of the Student American Medical Association, reprint, December 1955.

11 Medical Revolution in Minnesota.

12 Richard A. DeWall MD, “The origins of open heart surgery at the University of Minnesota 1951 to 1956,” The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Vol. 142, Issue 2, August 2011, pages 267–269,

sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022522311004211?via%3Dihub.

13 “The Mended Heart,” part of Open Heart: Intracardiac Surgery at the University of Minnesota, http://gallery.lib.umn.edu/exhibits/show/openheart/mended.

14 The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery.

15 The Open Heart Club.

16 The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery.