Japanese Language School at Camp Savage and Fort Snelling shortened World War II and brought people together

by Charlie Maguire

This article was originally published in Hennepin History Magazine, 2021, Vol. 80, No. 1

During World War II, some 5,000 to 6,000 Japanese American soldiers, members of the US Army’s Military Intelligence Service, were given intensive and accelerated classes in the Japanese language at Camp Savage. There subsequent work translating captured documents, maps, battle plans, diaries, letters, and printed materials, as well as interrogating Japanese prisoners made them “our human secret weapons,” according to President Truman, who commended them following the war.

Building 57-6341 Taylor Avenue, Fort Snelling

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 marked the beginning of the war for the US. It also established an ongoing educational institution that grew to maturity in Hennepin County. Some say that institution shortened the war by two years. We know it brought people together during a time of internal and external conflict. Additionally there was also an unlikely wartime bonus — an outpouring of good will for Japanese Americans by Hennepin County residents that was without equal in the rest of the nation.

Nisei Women’s Army Auxiliary Corp (WAAC) soldiers were also stationed at the language school. Privates Irene Tamigaki (left) and Akiko Mikami handle training files while stationed at Fort Snelling, 1944.

Soon after the surprise attack, the entire west coast of the United States was deemed a military area, and Executive Order 9066 called for the immediate removal of all Issei(Japanese immigrants) and Nisei(US citizens with Japanese parents) from those coastal states. Some 112,000 people were uprooted with only 48 hours notice. Homes, businesses, farms, neighbors, and friends were all left behind, and entire neighborhoods were relocated to barracks and tar-paper shacks hastily built at Manzanar in California, and a myriad of locations in New Mexico and other interior states.

The fact that we were also at war with Germany and Italy, and Americans of German or Italian ancestry were not rounded up, clearly shows racial discrimination. In retrospect, Professor Eugene Rostow of Yale University called the policy “our worst wartime mistake.” In fact, Executive Order 9066 remained on the books until it was repealed by President Gerald Ford in 1976. And the Civil Liberties Act, which amounted to a formal apology by the United States along with a $20,000 cash payment to surviving uprooted internees, didn’t happen until President Ronald Reagan signed it into law in 1988. Despite the chaos and abuse inflicted on US citizens of Japanese descent, American forces had to know how to read Japanese from captured plans and paperwork, and have the means to question Japanese prisoners in their own language.

Colonel Kai Rasmussen and Lieutenant William Tsuchiya sitting in a Japanese vehicle rebuilt by the Fort Snelling motor pool, just a quick march from the school, 1945.

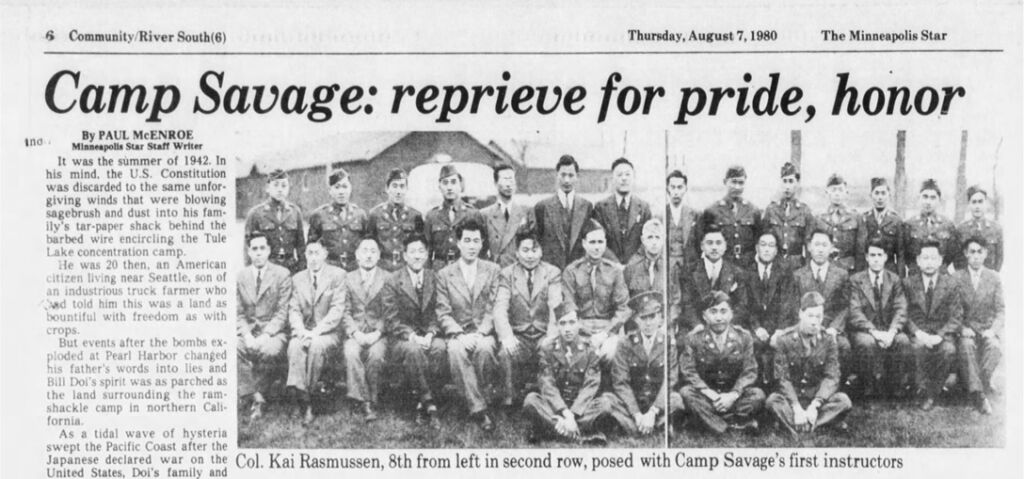

Enter Colonel Kai E. Rasmussen, a Danish-born US Army officer with the empathetic eyes of a teacher and the amused but stern demeanor of a high school principal. He had returned from Japan in 1940 after serving as an assistant military attache. Rasmussen convinced his superiors that a school needed to be established to study the Japanese language and culture. On November 1, 1941, the Military Intelligence Service Language School (MISLS) was created in Building 640, an old airplane hanger at the Presidio, near the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. With a $2,000 dollar budget and a six-month deadline, the first class, 58 Nisei and two white students, took their seats on orange crates. Rasmussen literally “wrote the book” on producing Japanese translators and linguists, using Japanese textbooks he had brought from his old post. He mimeographed copies of the texts for each student, and the Presidio’s carpenter was put to work building desks and chalkboards.

Months later, in May of 1942, the first class graduated and was sent to Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands. It was the first “island hopping” campaign that would eventually lead to the Japanese home islands three years later. Having soldiers in the field who could speak and read Japanese was a tactical coup. Soon every commander in the Pacific Theater wanted MISLS graduates. Hangar 640 was suddenly too small for the task. But where to go next? Acutely aware of the strained relations for the school being located on the West Coast, Rasmussen said it had to go to a place “that not only had the room physically, but room in the people’s hearts” for the Nisei students. After suffering rejection from other midwestern states, Rasmussen chose Minnesota and the Twin Cites area for its “racial amity,” which “would accept Japanese Americans for their true worth.” In June 1942, Minnesota Governor Harold Stassen signed off on the move.

Fort Snelling Japanese American Choir presents a New Year’s song program at St. Mark’s Episcopal Cathedral under the direction of Corporal Running, 1945.

The Military Intelligence Service Language School settled into Camp Savage, a Civilian Conservation Corps camp of 132 acres just outside of Savage. (Today the area is a dog park crowned with a historical sign marking the spot.) From the first class with 200 soldiers and instructors, it grew to 1,100 students and 92 instructors by 1944. A typical day was nine hours of Japanese language instruction, with a break for lunch and two and a half hours for dinner. Weekends were spent mostly hanging around on the base.

Many people may have had goodwill for the students, but Minnesotans weren’t overtly welcoming. The soldier-interpreters-to-be were typical American kids barely out of their teens trying to do their bit for the war effort. They were far from home; some had no experience with snow or cold weather; and above all, they felt confined and were having no fun. The Minneapolis Star and Tribune newspapers helped break the ice. The papers approached Rasmussen to bring a little social gaiety to the school in the form of a dance, with a live orchestra and employees “from our Star and Tribune offices,” as columnist George Grim wrote. After the dance, which was a huge success, “Our northwest,” Grim wrote, “soon understood these Nisei service men. Had them in their homes for dinner, for parties. Took them to church. Made them one of the family, the community.”

In 1944, Privates Iris Watanabe, Sue Agata, and Bette Nishimura, carrying civilian suitcases, were new arrivals at the school, which graduated over 6,000 students. Unlike army nurses, WAACs were not automatically given officer status.

Despite opportunities for students to venture off-site, the Savage camp was just too small for the school. It relocated again, for a third time, and took up residence in the old Band Barracks Building Number 57 at Fort Snelling. Built before the days of air conditioning, the stately brick edifice boasted expansive porches on either side of the entrance on both the first and second floors. Although the building is now mothballed, it is in good shape given that it was left unused for nearly 50 years. Amid the thick, mature oak trees, that were likely there during the war, it’s not hard to imagine students and their instructors quick-stepping to class, to the tune of 6,000 graduates by war’s end.

MISLS students’ lasting legacies

In the words of General Douglas MacArthur’s Chief of Staff for Military Intelligence, Major Charles Willoughby: “The Nisei shortened the Pacific war by two years, saved possibly a million American lives and billions of dollars.” From the portals of Building 57 came soldiers like Sergeant Kaz Kozaki, who won a Silver Star rescuing an officer under fire in New Guinea. Segeant Kenji Yasui swam across a river in Myitkyina, Myanmar, with two other volunteers and successfully talked 13 Japanese soldiers into surrendering. And Sergeant Frank T. Hachiya, born in Hood River, Oregon, volunteered to hike through the jungle with a patrol to question a prisoner and died when they were ambushed.

MISLS interpreters who were trained in Building 57 earned many awards: one Distinguished Service Cross, two Legion of Merit Awards, five Silver Stars, one Soldier’s Medal, 50 Bronze Stars, and 15 Purple Hearts — adding to the 18,000 decorations won by all Nisei troops in World War II that included 25 Medals of Honor. In 1946 the school was moved back to the West Coast, and Building 57 became a regional branch office for the Veterans Administration.

From the school’s new address in California came a check addressed to Minnesota Governor Edward Thye. The recently reassigned students had sent $1,236.05 (almost $17,000 in today’s currency) to fight the polio epidemic in a state that welcomed them wholeheartedly in wartime when hardly anyone else had. The Military Intelligence Language Service School changed its name in 1963 to the Defense Language Institute. But thanks to the growth and nurturing it received in places like Building 57, the school was never really closed. Just moved, then moved again, and back again under a new name that still welcomes language students today — who continue the work the school has tried to do: shorten wars and save lives.

had sent $1,236.05 (almost $17,000 in today’s currency) to fight the polio epidemic in a state that welcomed them wholeheartedly in wartime when hardly anyone else had. The Military Intelligence Language Service School changed its name in 1963 to the Defense Language Institute. But thanks to the growth and nurturing it received in places like Building 57, the school was never really closed. Just moved, then moved again, and back again under a new name that still welcomes language students today — who continue the work the school has tried to do: shorten wars and save lives.

The Military Intelligence Service Historic Learning Center at Crissy Field where it all started in November 1941, opened in 1993 as a joint project of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, the National Park Service, and the Presidio Trust. Its 10,000 square feet are devoted to preserving and interpreting the contribution of the Japanese American soldiers in WWII. While Building 57 may not look like much today, its rehabilitation is funded in part with the Minnesota state historic tax credit (see page 4) and slated to live again under a comprehensive plan formulated by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources and its partners.

University of Minnesota graduate student in political science, Ms. Kawahara, tests Japanese language knowledge with J.J. Elias and Richard Adams, both veterans and alumni of the Japanese Language School at Fort Snelling during the war. The two men were part of a Japanese-speaking Pearl Harbor Day luncheon at Nankin Cafe. 1946.

Charlie Maguire is a traveling songwriter, musician, and union organizer who makes frequent stops in Hennepin County.

PUT ON YOUR FLASHERS: Building 57 at Fort Snelling is easily reached by taking the exit for Bloomington Road at Fort Snelling and following the signs for the Fort Snelling Golf Course. You’ll come to a T, and Building 57 will be more or less in front of you. Take a left on Taylor Avenue, and park on the street.

Photos by Charlie Maguire unless otherwise noted.

SOURCES

- Milton Kaplan, “Snelling’s Jap Language School Proves Army Opposition Wrong.” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, October 23, 1945. Star Tribune Archive.

- “Our Nisei Neighbors.” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, June 8, 1946. Star Tribune Archive.

- “Jap Language School To Quit Fort Snelling.” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, March 9, 1946. Star Tribune Archive.

- “Beaten? Japs Don’t Like It.” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, March 8, 1946. Star Tribune Archive.

- George Grim, “Olive Skins, True Blue Hearts.” Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, September 15, 1946. Star Tribune Archive.

- Paul McEnroe, “Camp Savage: Reprieve for Pride, Honor.” Minneapolis Star, August 7, 1980. Star Tribune Archive.

- Natela Cutter, “Military Intelligence Service Historic Learning Center Opens.” November 26, 2013, army.mil.

- Fort Snelling Upper Post Interpretive Plan, 2006, parkplanning.nps.gov.

- Military Intelligence Service Historic Learning Center, njahs.org.

- MIS Historic Learning Center/National Japanese American Historical Society, parksconservancy.org.