July 28, 2022

The Glen Lake Sanatorium East Cottage, with fresh air tent. 1920.

Courtesy of Hopkins Historical Society.

What a marvel for scientists in the late 19th century to actually see what they theorized was making people ill. The world of bacteria and viruses was revealed because of increasingly powerful microscopes. Sanitarians turned those discoveries into public health policies regarding everything from sewage systems and clean water access to easily scrubbable wall paint and floor tiles in medical facilities.

An earlier sanitary movement had focused on infrastructure, particularly sewage systems and the availability of clean water. The new germ theory prompted sanitarians to consider environmental influences and how to keep illnesses from spreading through communities. The first attempts to sanitize environments occurred in medical settings. Sanitarians recommended nonabsorbent and scrubbable surfaces, as well as enamel paint. Terrazzo and tile replaced wood as a flooring. White or green tiles were installed on walls. Junctures between walls and floors were rounded to facilitate cleaning. Marble was used for windowsills and bathrooms. Roller shades replaced fabric curtains.1

These changes reflected the concern about dust and dirt as well as a myriad of infectious diseases: typhoid, diphtheria, smallpox, measles, chicken pox, cholera, whooping cough, and influenza. The new awareness of contagion coincided with a growing anti-tuberculosis movement, and these modifications became standard in tuberculosis sanatoriums built nationwide in the early 20th century. One trend was tied specifically to tuberculosis, however: the sleeping porch.

In the years before antibiotics, exposure to fresh air and sunshine was the only treatment that seemed to be effective in combatting tuberculosis. The first specialized facility in the United States was founded by Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau in the Adirondack Mountains town of Saranac Lake, New York, in 1885. A key feature of the sanatorium’s wooden cottages was the cure porch. Tuberculous patients would rest outside in reclining chairs during even the coldest days of winter. Sunbaths in warmer weather popularized the term “heliotherapy.”

Glen Lake Sanatorium, main infirmary building and east wing, with top-floor open terraces. Courtesy of Hopkins Historical Society.

When the Glen Lake Sanatorium opened in western Hennepin County in 1916, its two stucco cottages were built according to the sanitation model. Patients received the “fresh air method” in a tent outdoors. Glen Lake’s hospital infirmary was built in 1921. It and at least nine other county sanatoriums in Minnesota were designed by the Minneapolis firm of Engelbret Sund and Arthur Dunham. Their early constructions were in the Craftsman style and included large screened porches. Later designs included rooftop terraces and south-facing balconies so patients could be exposed to increased sunlight.2 Glen Lake’s building incorporated the fresh air and sunshine concept via 9-foot windows and an open terrace on the fifth floor. The two wings added to the infirmary in 1924 also featured terraces.

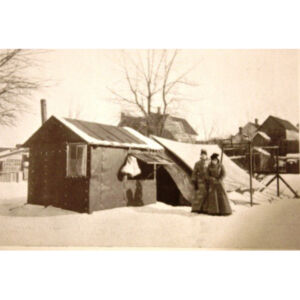

A Lampson portable sleeping porch, a temporary structure allowing a patient to be outside in all weathers.

The practice of beneficial exposure to the elements filtered into people’s homes. Anti-tuberculosis societies in several northern states, including Minnesota, had embraced the belief that cold fresh air was medicine. A popular charitable activity was the construction of window tents or hoods. These served a dual purpose by isolating the infected person from the family and providing the fresh air “cure.” Some canvas window tents projected from the open window to allow a special bed and the patient’s upper body to be outside, protected from rain or snow. Other designs allowed patients to remain in their own beds, but next to an open window. In either case, the closed tents limited transmission of tuberculosis to other members of the household.

Backyard shack and tent for tuberculosis cure. From the Report of the Anti-Tuberculosis Committee of the Associated Charities for the Year 1907.

More sophisticated accommodations included temporary lawn structures and detachable sleeping porches. In 1907, Dr. Henry L. Ulrich of Minneapolis published his plan for making a simple tent that

was devised to be “within the reach of the pocketbook of the poor.”3 The National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis published a 24-page pamphlet, Sleeping and Sitting in the Open Air.4 This amply illustrated booklet provided instructions for outdoor shelters ranging from tents to temporary porches erected on roofs or attached to existing structures. The publication also recommended suppliers of ready-made tents and bungalows, including the Des Moines Sleeping Porch Company in Iowa and the R. L Kenyon Company of Waukesha, Wisconsin.

The preferred solution was, however, a permanent sleeping porch. Although porches had been around for a long time, they were usually placed at first-floor level at the fronts or backs of houses and were a convenient place to sleep during summer heat waves. Sleeping porches for the prevention or treatment of disease were usually added to the top floor of an existing house or built as an integral part of a new one. Most porches had minimal walls, often having only screens for protection from bugs. Most houses that included a sleeping porch were built between the turn of the century and 1920.

Example of a sleeping porch added to the southwest corner of a house in south Minneapolis. A sleeping porch is not the same as a regular porch. If there is an entry to the house through the porch, that is not a sleeping porch.

By the 1920s, research had revealed more about tuberculosis as a disease. Resting the lungs was essential because it allowed fragile tissue to encapsulate the tuberculosis bacilli and render them inactive. Breathing cold fresh air required the lungs to work harder, which was counterproductive. Sunshine, while effective for bone tuberculosis, could exacerbate pulmonary tuberculosis by raising the temperature within the lungs. Furthermore, surgical interventions were becoming safer with aseptic techniques and the discovery of penicillin.

Amid all those wins, sleeping porches fell out of favor. Most were enclosed with windows and often they completely disappeared when a house got new siding. The book, A Guide to the Architecture of Minnesota cites the Hineline house at 4920 Dupont Avenue South, built in 1910. The entry points out that the “once-open screen porch to the south has now been enclosed.”5

In a further-reaching effect, the design of tuberculosis sanatoriums coincided with the advent of Modernism. Architectural elements like terraces and balconies and white or light-painted rooms spread across Europe. Part of the appeal of the extra outdoor space was its use for sunbathing. Modernist architects like Alvar Aalto brought form and function together into something akin to a hotel-hospital. His design for the seven-story Paimio Sanatorium near Turku in Finland featured balconies at the end of each residential wing, as well as a roof terrace.6

The overlap between Modernism and sanatorium design strengthened the movement’s association with health and hygiene. The Moderne style was used for several commercial buildings in Minnesota, most memorably the White Castle hamburger shops whose white porcelain panels and stainless-steel fixtures symbolized a hygienic eating experience. 7

Hygiene at home has been part of design for decades. After all, the main floor half-bath became popular in response to home deliveries by the iceman, the butcher, and the coal truck driver. It provided a space for them to use, without inviting them into the family’s living quarters.

What design trends will emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic? Will we have a more defined transition between the outside world and the inside of a home? More than ever before, people are acutely aware of protective equipment, the need for handwashing, and how germs spread both locally and globally. Maybe we will see an uptick in small hand-washing sinks or sanitizing areas near entrances to a home. Only time — and the continued meeting of art and science — will tell.

Mary Krugerud is the author of Interrupted Lives: The History of Tuberculosis in Minnesota and Glen Lake Sanatorium (North Star Press), The True Story of a Teenage Tuberculosis Patient (Minnesota Historical Society Press). She also curated Hennepin History Museum’s 2018 exhibit

A Look at Glen Lake Tuberculosis Sanatorium.

Endnotes

1 Leslie Maitland, “The Design of Tuberculosis Sanatoria in Late Nineteenth Century Canada,” Bulletin: Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada. March 1989. V.14, N.1, p. 5. Quoting from Albert J. Ochsner and Meyer J. Sturm, The Organization, Construction, and Management of Hospitals, 2nd ed. Chicago: Cleveland Press, 1909.

2 Rolf T. Anderson, “Pastoral Remedies: At Minnesota’s Tuberculosis Sanatoriums, Site and Design Meant to Heal.” Minnesota Architecture. The Sund and Dunham architectural firm formed in 1911. They designed many schools, churches, and institutions in Minneapolis and Saint Paul, as well as the Moose Lake State Hospital and several buildings at the Ah Gwah Ching State Sanatorium at Walker.

3 Henry L. Ulrich, “A Simple Sanatory [sic] Tent.” St. Paul Medical Journal, 1904, quoted on p. 220 of J. Arthur Myers, Invited and Conquered: Historical Sketch of Tuberculosis in Minnesota. St. Paul: Webb Publishing, 1949.

4 National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis. Sleeping and Sitting in the Open Air. New York, 1917.

5 David Gebhard and Tom Martinson, A Guide to the Architecture of Minnesota. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1977, p.71. The house was designed by Purcell, Feick, and Elmslie.

6 Helen Bynum, Spitting Blood: The History of Tuberculosis. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2012, pp. 128–29.

7 Gebhard and Martinson, p. 16.