April 29, 2022

Before Marian Anderson was denied Constitution Hall, Minneapolis’ Dyckman Hotel refused the famous contralto lodging

by Jokeda “JoJo” Bell

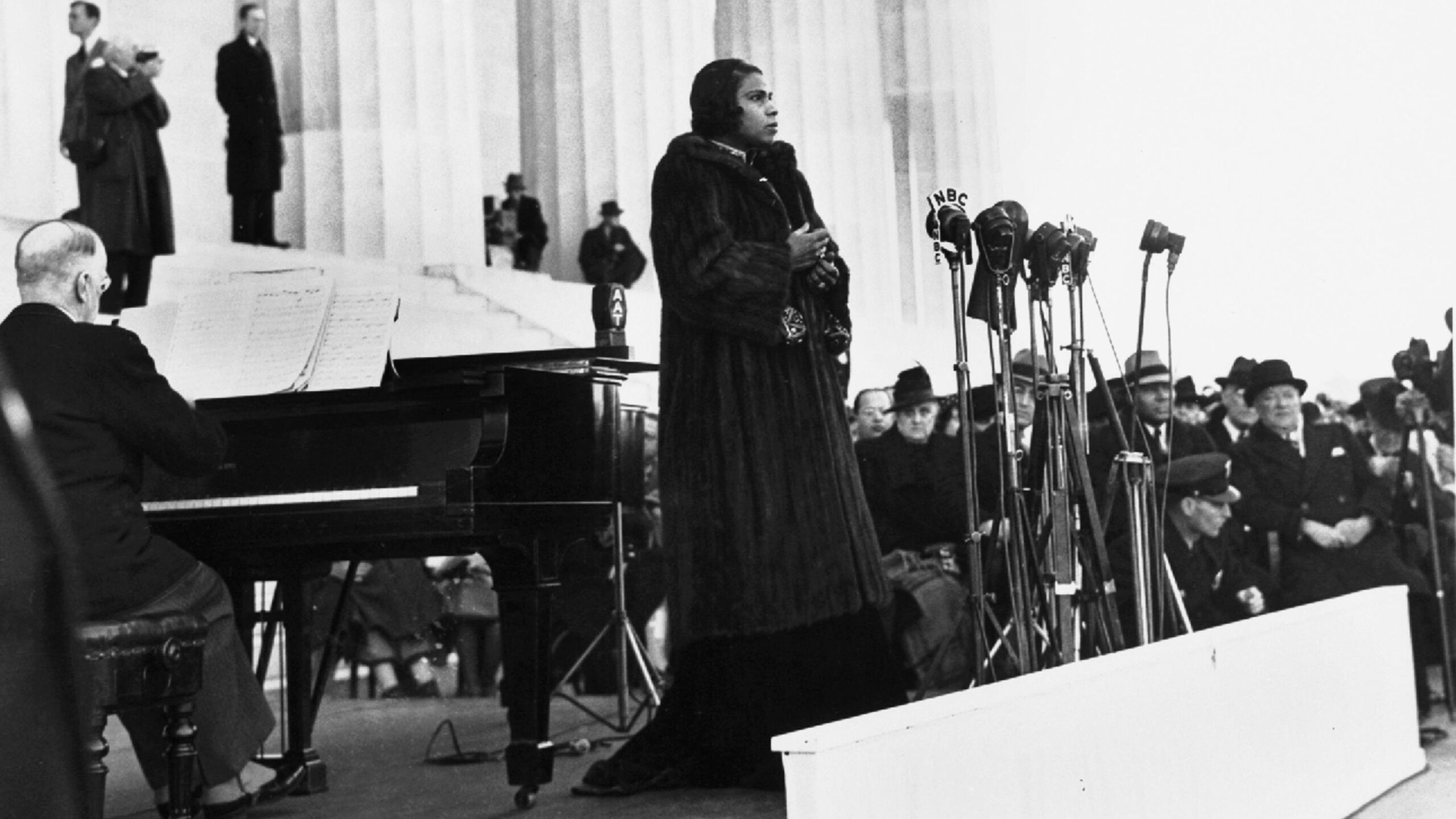

Marian Anderson’s most famous challenge to American Jim Crow occurred during her April 9, 1939, performance at the Lincoln Memorial. After the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) denied Anderson the segregated Constitution Hall for her Easter Sunday concert, she was offered the steps of the Lincoln Memorial by Eleanor Roosevelt. Although Anderson didn’t get the Hall, her challenge to the DAR — considered a catalyst of the American civil rights movement — was supported by the NAACP and contested the legality of denying Black people rights based on race. It was monumental. It also wasn’t the first time Anderson defied entrenched racial segregation. In March of the same year, Minneapolis broke into protest when the famous opera singer was denied accommodations at the Dyckman Hotel downtown.

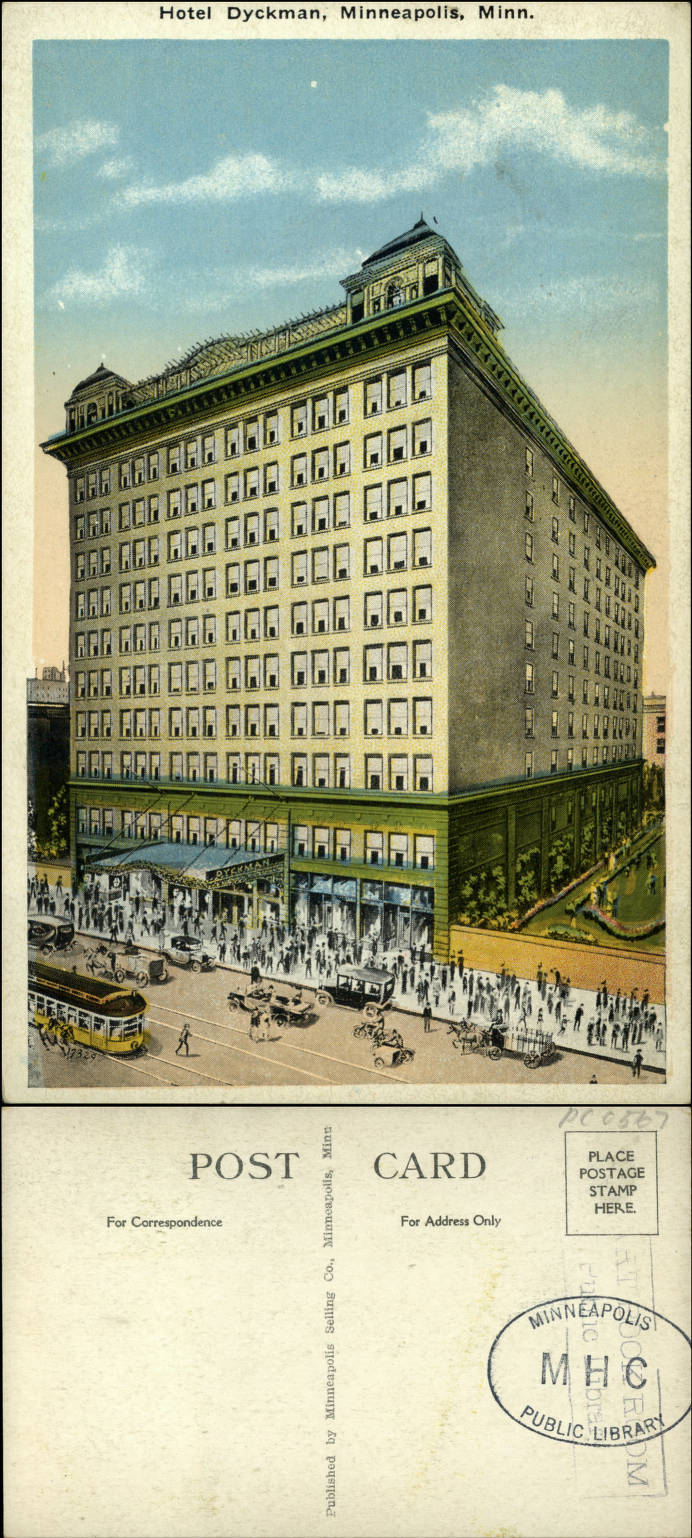

The Dyckman Hotel opened in 1910 and its Italianate style offered luxury not often associated with flyover country. According to author Jack El-Hai, the Dyckman boasted private bathrooms, telephones in each room, and a lobby made of mahogany and marble.1 To add to the hotel’s mystique, it is rumored that smugglers furnished the hotel with liquor during Prohibition. The luxurious décor of the Dyckman attracted a certain set of patrons, and Marian Anderson — one of the most famous entertainers in America — had her heart set on staying at the sumptuous hotel when she came to town in 1939.

Anderson’s performance at the Minneapolis Auditorium in February 1939 was not the singer’s first event in Minnesota. On previous tour stops in Minnesota, Anderson stayed at the Phyllis Wheatley House.2 At the height of the Great Migration, cities like New York, Detroit, and Chicago — cities that already had a sizable Black population — saw an influx of Black southerners. Cities in Minnesota hardly saw the arrival of new transplants the way that larger, more industrial Great Migration stations did. The Mill City saw only a 2.4 percent rise in the number of Black citizens between 1910 and 1940.3 The new arrivals found support at the Phyllis Wheatley House, a settlement home constructed in 1924 that provided Black Minnesotans with social and recreation programs.4 Wheatley also provided lodging for Black entertainers and intellectuals who were denied accommodation at hotels around the city. Anderson was no exception and used her stays at Wheatley to interact on a personal level with staff and patrons. But 1939 was different; this time the Wheatley House would become the base of operations for the protest against the Dyckman Hotel — the upscale hotel that denied accommodations to the most famous Black contralto in the nation.

Gathering momentum

No firsthand accounts of Anderson’s motivation to request a room at the Dyckman Hotel exist. One could wonder if the Dyckman was on Anderson’s radar as she was in the midst of her showdown with the DAR. If she could successfully get an upscale room in Minneapolis, surely the Daughters of the American Revolution would rethink their refusal to host her at Constitution Hall. Whatever Anderson’s motive, the bottom line was she was denied a room. Once the Women’s Christian Association — a partner of the Phyllis Wheatley House — got wind of the Dyckman’s actions against the opera singer, they helped organize a protest against the hotel.

The protest included the NAACP, its youth chapter, the Women’s Christian Association and white and Black residents of the city. As protesters picketed downtown Minneapolis at 6th Street and Hennepin Avenue — in front of the Dyckman — the local NAACP chapter tried its best to shield its younger members from the vitriol of the counterprotesters. In his memoir, local civil rights activist Harry Davis recounted the treatment the protesters received from their fellow Minnesotans: taunts, spitting, and physical abuse were all tactics employed against them in an effort

to deter their activism. Their protests spread to the Minneapolis Auditorium; the city was grappling with unrest, a blow to its progressive image. The Dyckman Hotel caved and offered Anderson a room — with a caveat: she was to enter through the backdoor. Members of the Women’s Christian Association did not accept these terms and Anderson was later offered unrestricted access to the hotel including use of the front door and all the amenities offered to its white clientele.

The protests seemed to have little effect on the local DAR. Minnesota’s chapter involved themselves in the national defense of the DAR and voted 39 to 1 to support the DC chapter’s barring of Anderson from Constitution Hall.5 The group’s reasoning for siding with its Washington affiliate was vague, but hinted at the true nature for the support of Jim Crow: “. . . had Miss Anderson been permitted to sing, it [Constitution Hall] would have had to face a loss in revenue.” The Spokesman added, “No explanation of how this loss would be brought about was offered.” 6

More doors close — quietly

Anderson faced the same discriminatory practices in the city of Duluth. According to a 1940 article by the Minneapolis Spokesman, Anderson had previously been denied accommodations in Duluth when both she and legendary singer Paul Robeson made tour stops in the city. Anderson was in town for a 1938 concert and Robeson stopped in the city in 1931. When challenged, the manager of an unnamed hotel had made an exception for Paul Robeson, as long as he agreed to use the freight elevator. Although the Spokesman mentions the outcome for Robeson, it did not mention where Anderson stayed. In fact, the only mention of Anderson’s traumatic confrontation with segregationist policies in Duluth was a line at the beginning of the report that states, “[a]n outstanding victory against jim-crow [sic] in this city [Duluth] was scored here on September 18th. The victory helped to square accounts for the shameful treatment accorded the artists Paul Robeson and Marian Anderson, who were refused lodging when they were in Duluth on a concert tour.” 7

The paper was attempting to tie the treatment of Robeson and Anderson to an incident that happened in 1940 involving political figures William Patterson and Erik Bert at the Spalding Hotel in Duluth. Patterson was a candidate for Congress from Illinois, and Erik Bert was the secretary for the Minnesota campaign committee of the Community Party.8

The Spalding Hotel opened in 1889 to fanfare in the local press. By the time Patterson and Bert requested a room in 1940, it was in decline. Competition from newer hotels and the increasing grittiness of the surrounding post-war neighborhood took away from the allure of the once-grand establishment.9 When Patterson and Bert requested accommodations at The Spalding, they were denied on the basis of race and political affiliation. Robeson was also associated with the American Communist Party. For its part, the Spalding frankly told the men that, “we do not cater to colored people,” but if they wanted a room, they would have to pay $35.00 instead of the standard $3.50.10 When the men successfully challenged the policy, the Spokesman reported their win as a win for all Black people denied accommodations in the city of Duluth, including Robeson and Anderson.

For Anderson, rejection in Duluth may have conjured past anxieties from Constitution Hall’s denial of concert space following the initial denial of accommodation from the Dyckman. But further reporting on Anderson’s experience in Duluth seems to be limited to a line about the issue being settled for Bert and Patterson and how that “squares” the pain Anderson and Robeson faced when denied hotel rooms in the city. The racial segregationist policies employed by the Dyckman and Spalding Hotels highlight an important fact about the practice of Jim Crow: Black people who visited and lived in the North were not shielded from the racism experienced by their counterparts in the South. These acts also manifested the true, insidious nature of segregation. You could win the battle and still face a never-ending war against American racism. Marian Anderson found this to be true in the nation’s capital, Duluth, and our own backyard.

Jokeda “JoJo” Bell, is the executive director and the director of exhibitions and programming for the African American Interpretive Center of Minnesota. She is currently writing a book about Hilda Simm, to be published by the Minnesota Historical Society Press.

FOOTNOTES

1 El-Hai, Jack. Lost Minnesota: Stories of Vanished Places. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2000.

2 Davis, W. Harry, and Lori Sturdevant. Overcoming: The Autobiography of

W. Harry Davis. Afton, MN: Afton Historical Society Press, 2002.

3 Gibson, Campbell, and Kay Jung. Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals by Race, 1790 to 1990, and By Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, For Large Cities and Other Urban Places in The United States, Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals by Race, 1790 to 1990, and By Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, For Large Cities and Other Urban Places in The United States § (2005).

4 Karger, Howard Jacob. “Phyllis Wheatley House: A History of the Minneapolis Black Settlement House, 1924 to 1940.” Phyl5 (1960–)

47, no. 1 (1986): 79–90. Accessed April 20, 2021. doi:10.2307/274697.

5 Minnesota DAR Astounds State, Endorses Barring Marian Anderson

in D.C.” Minneapolis Spokesman. March 17, 1939.

6 Ibid.

7 “Threat to Picket Spalding Hotel Brings a Manager’s Capitulation.” Minneapolis Spokesman. October 4, 1940.

8 Ibid.

9 Krueger, Andrew. “Duluth’s Jewel from the 1800s, Spalding Hotel Fell

to Urban Renewal 50 Years Ago,” December 13, 2013. duluthnewstribune.com/news/2454645-duluths-jewel-1800s-spalding-hotel-fell-urban-renewal-50-years.

10 “Threat to Picket Spalding Hotel Brings a Manager’s Capitulation.” Minneapolis Spokesman. October 4, 1940.

CAPTION/CREDITS

Marian Anderson sings to crowd from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on April 9, 1939. Public domain photo, Wikimedia Commons.