From the Land of the Golden Grain: The Origins and Early Years of the Minneapolis Brewing Company

by Michael R. Worcester

This article was originally published in Hennepin History, Fall 1992, Vol. 51, No. 4

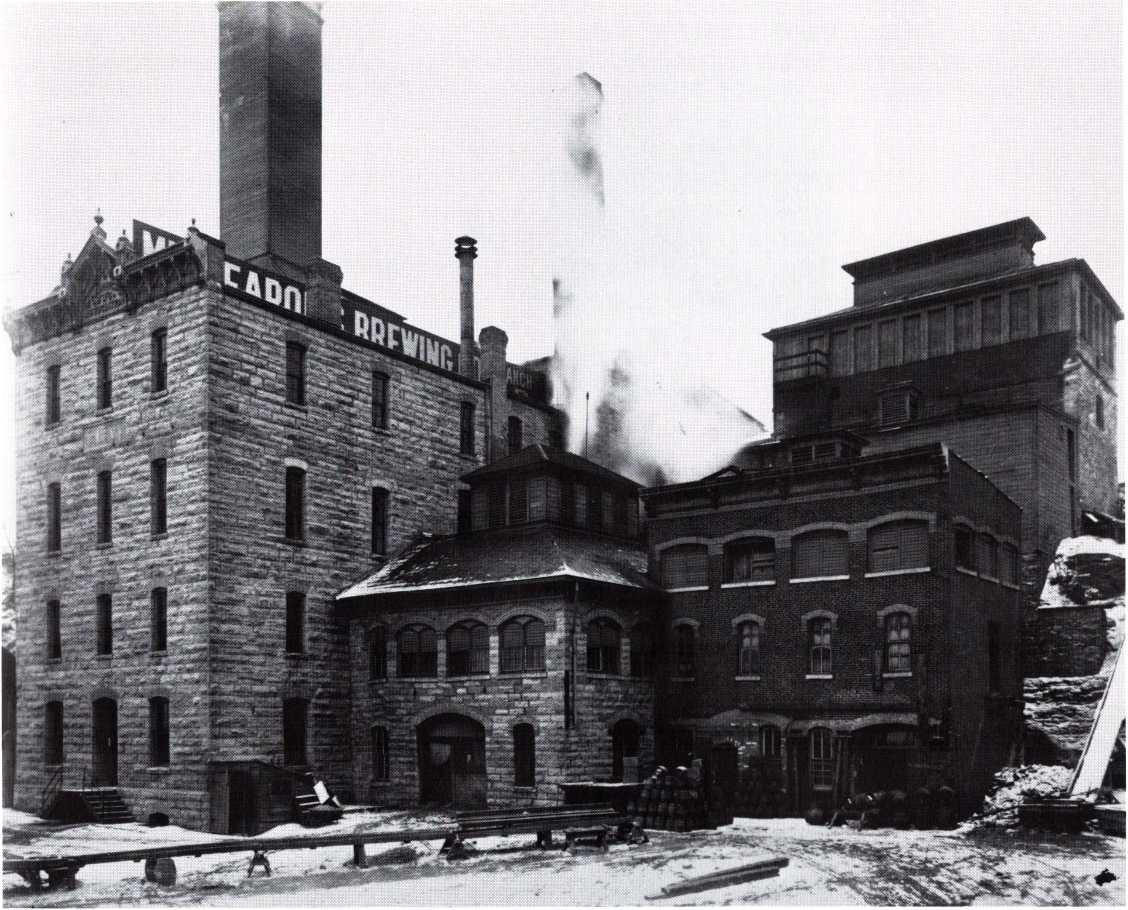

The Minneapolis Brewing Company, 1215 Northeast Marshall Street, Minneapolis, ca. 1900. Photo credit: Minnesota Historical Society

THE BEER IS BACK, proclaim the advertisements. The words are seen and heard in many places—“the beer is back.” To most observers, the phrase refers to the reopening of the former Jacob Schmidt Brewery in St. Paul by the recently formed Minnesota Brewing Company and to the introduction of its new label, Landmark Beer. But these words also symbolize a different return, a homecoming of sorts. For hidden in all the hoopla and celebration is the return to the state after a 17-year absence of a Minnesota original, Grain Belt Beer. The Minnesota Brewing Company has purchased the old label and is brewing the beer again in the state. The lack of fanfare surrounding Grain Belt’s return ignores what was perhaps one of the greatest successes in the history of brewing in Minnesota. For 85 years, Grain Belt Beer and its parent, the Minneapolis Brewing Company (it did not become Grain Belt Breweries, Inc., until 1967), were synonymous with the state’s brewing industry. For many years Grain Belt captured almost one- third of the Minnesota brewers’ market, and it ranked in the top 25 nationally. The former home of Grain Belt has sat abandoned in northeast Minneapolis since 1975, a stark reminder of the better days brewing has seen in Minnesota. The story of the inception of this former brewing giant, and of brewing in the state in general, is often overlooked.

The brewing industry in Minnesota had its start very early. To be precise, Minnesota was not even a territory when its first brewery was founded. Anthony Yoerg opened a brewery in St. Paul in 1848, and by 1860 over a dozen breweries were operating in the two-year-old state, in cities and towns like Winona, Mankato, Minneapolis, St. Cloud, and New Ulm.2 Several factors helped to drive this early growth. The first was the influence of German immigrants (who provided a ready market for good beer brewed by Germans) in the state. Of the 14 breweries operating in 1860, only one was run by a person of non-German ethnicity.3 This pattern would hold steady through much of the industry’s early development.4 One example is that of Ramsey County, which by 1878 counted 3,600 German- born persons in its population and 11 fully operating breweries. Hennepin County had a similar though slightly smaller ratio, with 2,900 German-born residents and four breweries. Other counties boasting comparable ratios included Scott, Stearns, and Brown counties, all of which had large concentrations of German immigrants.5

Another factor was the plentiful and readily available supply of Minnesota’s barley crop. Between 1878 and 1880, when the number of breweries in Minnesota peaked at 114, farmers produced three million bushels of barley. Even though not all of the crop was used for malting, the premium price brewers paid for good-quality barley and the steady growth of beer production (which used approximately one bushel of barley per barrel of beer 7) proved beneficial to both industries. Technological changes in the brewing process, particularly the pasteurization of beer, boosted the ability of brewers to ship their product longer distances without fear of spoilage. That, coupled with artificial refrigeration and ice production, and thus the wide use of refrigerated railroad cars, enabled beer production to grow at a tremendous rate. Even though the number of breweries in the state fell by 25 between 1875 and 1900, actual production grew by over 700,000 barrels.8 During this turbulent period of pre-twentieth-century Minnesota beer production, the Minneapolis Brewing Company saw its genesis.

For 85 years, Grain Belt Beer and its parent, the Minneapolis Brewing Company, were synonymous with the states brewing industry.

Orth Brewery, 1228 Marshall Street Northeast, Minneapolis, ca. 1880. John Orth stands in the foreground, left.

Minneapolis, ca. 1890, was a thriving urban center. Its growth was steady and fast-paced, and it was quickly becoming the industrial center of the Upper Midwest, as evidenced by its most prominent industry, flour-milling. Operating in the shadows of the milling giants were five small breweries: the Germania Brewing Association, the F. D. Noerenberg Brewing Company, the Heinreich Brewing Association, John Orth Brewing Company, and the Gluek Brewing Company. In July 1890, four of the five companies, Gluek being the exception, merged to form the Minneapolis Brewing and Malting Company.9 But before we look at the origins of Grain Belt’s parent, let’s trace the stories of those who formed it, beginning with the arrival of a German ethnic, John Orth.

John Orth Brewing Company

John Orth was born in the Alsace province of France in 1821, and arrived in Minneapolis via Erie, Pennsylvania, in 1850.10 Orth holds the distinction of founding the second brewery in Minnesota, which he did shortly after his arrival. This also made Orth the first person to produce beer in Hennepin County. Until the founding of Gottlieb Gluek’s Mississippi Brewery in 1857, Orth was the only brewer in St. Anthony or Minneapolis. Orth was active in the civic life of both St. Anthony and Minneapolis. He was elected as one of the first aldermen of St. Anthony in 1855 and the consolidated City of Minneapolis in 1872.11 A respected member of the community, Orth was active in the Republican party and was dedicated to the antislavery movement, though in later years he switched his allegiance to the Democratic party. Orth was president of the company until his death in June 1887, when the mantle passed to his son John W. Orth.12 Together with his brothers Alfred H. and Edward F., the younger Orth Heinrich Brewing Building at operated the company until the merger.

Heinreich Brewing Association

Joining Orth and Gluek in the local brewing scene in 1866 was the firm of Kranzlein & Mueller. The Minneapolis Brewery, as it was called, was founded by John G. Kranzlein and John B. Mueller, who established their company on the shores of the lower Mississippi, just south of the Falls of St. Anthony.13 Tracing the early years of Kranzlein & Mueller is difficult because of inconsistencies in early histories of Minneapolis, but their partnership apparently dissolved in 1869. Kranzlein remained to operate the company until 1874, when Mueller returned with a partner, John Heinreich, and they purchased the brewery from Kranzlein.14 Together Mueller and Heinreich made numerous improvements to the plant, by 1879 making it the third largest producer of beer in the state, at just over 8,000 barrels per year.15 Heinreich bought out Mueller in 1884 and ran the brewery, which then became known as the Heinreich Brewing Association, with the assistance of his three sons, Adolph C., Gustav J., and Julius. John Heinreich died sometime in 1889, and his sons took over the operation of the company. They maintained the brewery until the merger, at which time the company was valued at $225,000.16

F. D. Noerenberg Brewing Company

In 1874, Anton Zahler founded the (dry Brewery on a bluff overlooking the Mississippi River, near what is now 20th Avenue South. Little is known about Zahler or the early years of his brewing business. In 1877, he took as a partner Frederich D. Noerenberg, who had recently moved to Minneapolis from St. Paul, where he had kept a hotel.18 Within two years their company, Zahler & Noerenberg, was the second-leading producer of beer in Minnesota, trailing only St. Paul-based Christian Stahlman.19 Highlighting the family nature of the brewing industry was that Noerenberg’s brother, August J., was the bottler for Frederich’s products under the name A. J. Noerenberg Bottling Works. Upon Zahler’s death in May 1880, Noerenberg took full control of the company, serving as its president until the merger.20

Germania Brewing Association

The youngest of the four merging breweries was the Germania Brewing Association. Located on the shores of Kegans Lake (now Wirth Lake), Germania was founded in 1887 by Herman A. Westphal and John B. Mueller, the same Mueller who had been with Heinreich Brewing.21 Westphal had for several years operated the City Ice Company; the two men built their brewery next to one of his icehouses. As with Zahler & Noerenbergs brewery, little is known about how successful Germania was. With an output of fewer than 2,000 barrels per year, it was a fairly small company. Its officers aside from the owners included John Van der Horck and Jacob Barge. Mueller committed suicide, however, and Westphal returned to the ice business just a few short weeks before the four breweries merged.22

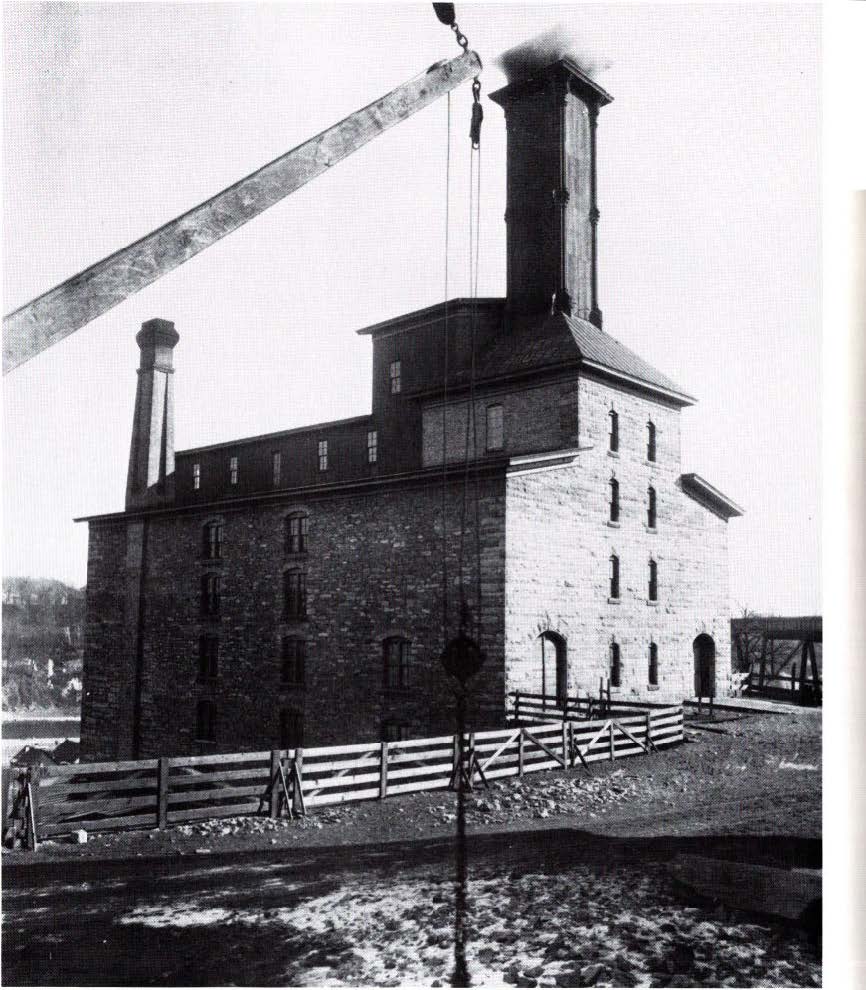

Heinrich Brewing Building at f00t of 4th Street Minneapolis, ca. 1895

Noerenberg’s Brewery near the 10th Avenue bridge, Minneapolis, ca. 1885.

Germania Brewery, Western Avenue and Kegans Lake (now Wirth Lake), Minneapolis, 1888-89.

An ad in the Dual City Blue Book, 1893-1894

The main motivations leading to the merger have never been explicitly stated. Large mergers were a common phenomenon in the brewing industry at the time. Mergers involving as many as 18 separate breweries were occurring in cities such as Milwaukee, Pittsburgh, New Orleans, and St. Louis. Brewing historian Stanley Baron asserts that the mergers were “a reflection of anxiety within the industry.”23 This “merger-mania” was not limited to the brewing business. The railroad, mining, and steel industries were all experiencing similar merger movements. In all likelihood, the four Minneapolis breweries (Orth, Heinreich, Germania, and Noerenberg) saw merging as an option ensuring their mutual survival. In July 1890, the four companies joined to form the Minneapolis Brewing & Making Company.24 As the largest and most modern facility, the Orth brewery was chosen as the principal company plant. The Heinreich and Germania plants were also used for a couple of years. The Noerenberg location, however, for reasons unknown, was left idle, though from 1901 to 1905 it was leased to the Imperial Brewing Company for its brewing operation.25 The officers of the new company were listed as follows: John W. Orth-—President, Frederich D. Noerenberg—1st Vice President, Alfred H. Orth—2nd Vice President, Jacob Barge—Secretary, Gustav J. Heinreich—Treasurer/Man- ager, Titus Mareck—Assistant Manager, and Conrad Birkhofer—Superintendent.

In July 1892, Minneapolis Brewing & Malting constructed the building that was to be the company’s home for the next 83 years. Built on the site of the Orth complex at 1215 Northeast Marshall Street, this massive structure was one of the most modern as well as one of the largest facilities in the nation. Additions made over the next decade would bring its annual production capacity to a half-million barrels.26 Entering a market as competitive as the late-nineteenth-century beer market was going to be no easy task. Minneapolis Brewing attempted to find a niche in part through inventive advertising. One of its 1892 advertisements, for instance, read: “We make four kinds of beer: the Weiner, which has a malty taste and is made for the families; the Extra Pale, the palest beer made, also for family use and having a taste of hops; Dark Lager, a heavy beverage; and the London Porter.”27 A bottle label from the Minneapolis Brewing brand read: “As a family beverage, this beer is a perfect tonic promoting restful sleep and aiding appetite,” and “Bottled direct from glass tanks and properly sterilized. Will not cause biliousness.”28 (Biliousness is the excess production of stomach bile.) Such emphasis on the healthier aspects of beer consumption was most likely utilized as a tactic to counter well-organized temperance forces such as the Anti-Saloon League, which became quite active during that period.

Some early activities undertaken by Minneapolis Brewing, indicative of the industry’s nature at the time, seem somewhat shady by modern standards. In particular, the practice of maintaining what were called “tied-houses” could be called into question. These were created when a brewing company lent money to an individual for, among other things, procurement of a liquor license, or to purchase saloon fixtures, or to expand a beer garden. In exchange, only the products made by the company supplying the loan would be served at the establishment.29 This practice, as Stanley Baron has described it, was “universal” among brewers throughout the country. An idea imported from Great Britain and Germany, it was adapted to the American brewing industry. Breweries maintained this method until Prohibition, after which it was outlawed.30

The four Minneapolis breweries saw merging as an option ensuring their mutual survival.

In 1893, the company reorganized and was incorporated under the name Minneapolis Brewing Company. The new leadership of the company included Matthias J. Bofferding—President, Frederich D. Noerenberg—Vice President, Titus Mareck—Secretary, and Gustav J. Heinreich—Treasurer. The entire Orth family had by this time departed from the operations of the company, marking the end of a brewing era begun in 1850. Soon afterwards, the Orths went into the real estate business as the Orth Brothers. In later years they operated the City Ice Company. Joining the new officers as directors were such prominent Minneapolis businessmen as Albert C. Cobb, Jacob Kunz, and William W. Eastman. Later, in 1893, Eastman would rise to the post of company president upon Bofferding’s death. That year—1893—also saw Minneapolis Brewing introduce the trademark that would eventually outlive its parent, Golden Grain Belt Beer.

To help market its products, Minneapolis Brewing set up associated agencies in cities as close as St. Cloud and as far away as Calumet, Michigan.31 By 1905, the Minneapolis Brewing Company complex had become like a small village, with such village staples as a machine shop, a carpenter shop, a paint shop, and a wagon shop.32 During the years before Prohibition, Minneapolis Brewing marketed, in addition to Grain Belt, beers with such names as MBC Pale Dry, Edelweiss, Minnehaha Ale, and Zumalweiss. A promotional item for Zumalweiss included a song sheet titled “Zum-Zum-Zum: A Stein Song.”33 Minneapolis Brewing attempted to ride out Prohibition by producing near- beer, soda, and fruit juice under the name Golden Grain Juice Company. It also marketed rubbing alcohols and other spirits as the Kunz Preparations Company. Minneapolis Brewing was able to survive until 1929 but only at a tremendous financial cost. In the end, it was forced, like so many others, to shut down and wait until the repeal of Prohibition in 1933.34 Following repeal, Minneapolis Brewing returned to the Minnesota brewing scene, as did Grain Belt Beer. The company became a central figure in the state beer market, continuing so for another 42 years. In 1975 the company was sold, the brewery was closed, and Grain Belt Beer left the state for production by the G. Heileman Brewing Company of La Crosse, Wisconsin. But now “the beer is back” in Minnesota, where it began. And even though Grain Belt’s former home remains idle, it silently oversees a new age of brewing—an era that John Orth, F. D. Noerenberg, the Heinreich family, and all the workers who toiled through the years to make Grain Belt beer so popular, would probably find most gratifying indeed.

Michael Worcester is a graduate student in public history at St. Cloud State University, where he is researching the Minneapolis Brewing Company for his master’s thesis. He adapted this article from his paper prepared for the Minnesota History Conference at the University of Minnesota in April 1992.

An ad in the Minneapolis City Directory, 1898.

An ad in the Minneapolis City Directory, 1895—96

References

1. Charles F. Keithahn, The Brewing Industry (Washington D.C.: Federal Trade Commission, Bureau of Economics, 1978), 62.

2. Donald Bull, American Breiueries (Trumbull, Connecticut: Bullworks, 1984), 136-49.

3. Charles E. Dick, “A Geographical Analysis of the Development of the Brewing Industry in Minnesota,” Ph.D. diss., University of Minnesota, 1981, p.204.

4. D. Jerome Tweton, “The Business of Agriculture” in Clifford Clark, ed., Minnesota in a Century of Change: The State and Its People Since 1900 (St.Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1989), 285.

5. Peter Rachleff, Labor: Three Key Conflicts” in Clifford Clark, ed., Minnesota in a Century of Change: The State and Its People Since 1900 (St. Paul, Minnesota Historical Society Press, 19891,207-08.

6. Ibid.

7. Tweton, “The Business of Agriculture,”287.

8. One Hundred Years of Brewing (Chicago:H. S. Rich & Company, 1903), 608-10.

9. Bull, American Breweries, 142-43.

10. Michael Hajicek, “History of the Minneapolis Brewing Company,” Breweriana Collector (Summer 1989), 16.

11. Marion D. Shutter, ed., History of Minneapolis: Gateway to the Northwest (Chicago/Minneapolis: S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1932), 101, 113.

12. Ron Feldhaus, The Bottles, Breweriana, and Advertising Jugs of Minnesota, 1850-1920 (Minneapolis: North Star Historic Bottle Collectors Association, 1986), 23.

13. George E. Warner, History of Hennepin County and the City of Minneapolis (Minneapolis: North Star Publishing,1881), 421.

14. Ibid.

15. Dick, A Geographical Analysis, 97.

16. Feldhaus, Bottles, Breweriana, and Advertising Jugs, 18.

17. Ibid., 11.

18. Bull, American Breweries, 143.

19. Dick, ‘A Geographical Analysis,” 97.

20. Feldhaus, Bottles, Breweriana, and Advertising Jugs, 11.

21. Bull, American Breweries, 142.

22. Feldhaus, Bottles, Breweriana, and Advertising Jugs, 12, 19.

23. Stanley Baron, Brewed in America: A History of Beer and Ale in the United States (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1962), 132-35.

24. Bull, American Breweries, 142-43.

25. Feldhaus, Bottles, Breweriana, and Advertising Jugs, 11-23.

26. One Hundred Years of Brewing, 514.

27. Feldhaus, Bottles, Breweriana, and Advertising Jugs, 19.

28. Hajicek, “History of the Minneapolis Brewing Company,” 16.

29. Records of Grain Belt Breweries, Inc., 1890-1975. Minnesota Historical Society.

30. Baron, Brewed iti America, 168-70.

31. Hajicek, “History of the Minneapolis Brewing Company,” 16.

32. Ibid., 17.

33. Ibid.

34. Records of Grain Belt Breweries, Inc.