Edifices for Educators: Buildings Named for University Women

By Claire Strom

This article was originally published in Hennepin History Magazine, Spring 1991, Vol. 50, No 2

Organizations have always found ways to honor the achievements of their members. The Catholic Church makes saints, the military awards medals, and the English monarchy creates knights. Each organization bestows awards appropriate to its nature, and within universities this often involves remembering outstanding people by naming buildings after them.

Academia has historically been populated mainly by men and , consequently, by far the greatest number of buildings at the University of Minnesota are named for them. However, in this century , seven buildings have been named after women. Who were these women? Why did they deserve this honor? And does the university display any consistency in its choices?

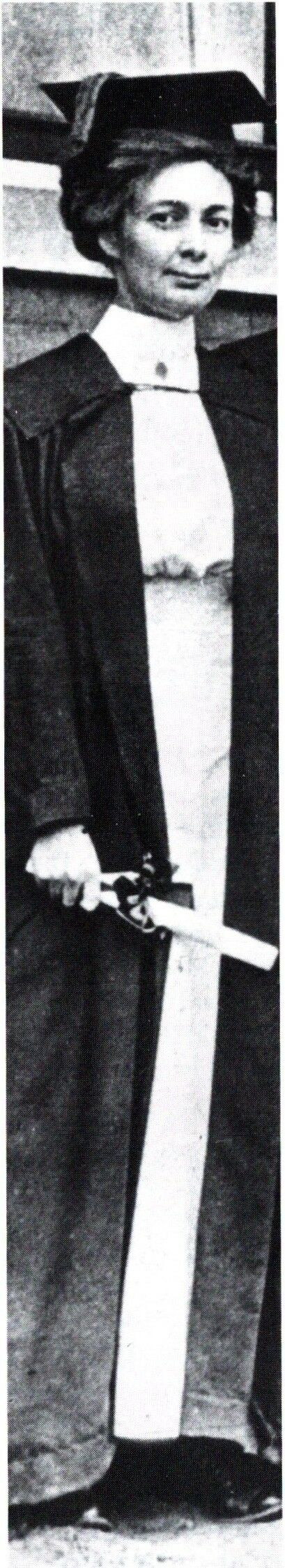

Maria Sanford taught at the University of Minnesota for nearly 30 years.

MARIA SANFORD (1836-1920)

Maria Sanford was born in Saybrook, Connecticut. Her decision to teach was made early when she asked her father for her dowry money in order to attend the New Britain Normal School. She taught in schools in Connecticut and Pennsylvania, and in 1869 she became a teacher of English and history at the Quaker college of Swarthmore. In 1870 she became professor of history and thus the first female professor in the United States. In 1879 she resigned, and in 1880 she came to the University of Minnesota as an assistant professor of rhetoric and elocution. She stayed at the university until she retired at the age of 73. She then increased her public lecturing and taught in the university’s new Extension program.

Sanford ‘s career at the university was far from smooth. Not only was she one of the few women teaching there at that time, but she was also headstrong and eccentric. It was these traits that repeatedly landed her in trouble. She refused to modernize her dress and wore only baggy, black, mid-Victorian dresses. This made her look strange, and when she walked across campus she picked up litter and put it in her long skirt. She later burned the litter in the classroom fire. Her behavior was considered unacceptable.

She expected her students to write an essay per week instead of the requisite two per term, and she held classes at odd times – “Maria’s Sunrise Class” was infamous. All of this resulted in her being caricatured in student productions and finally in a petition being presented to President Northrop asking for her dismissal. Nothing came of this petition and , although Sanford did not change, her eccentricities were gradually accepted and finally even cherished by her students. At the end of her first decade at the university, some students wrote a poem recognizing her good qualities as well as her eccentric ones:

Though she’s always in a hurry,

in a flutter, and a flurry,

And she never seems attired for the ball;

Noble qualities defend herand her soul is warm and tender

She’s a pretty good Maria after all.

She worked very hard at her lecturing, sometimes speaking as many as four or five nights a week, and after retirement from the university expanded her circuit. In 1912, after addressing the bicentennial meeting of the National Federation of Women’s Clubs in San Francisco, her circuit increased even further until by 1915 it included California, Montana, North Dakota and New York. Like other forms of oral entertainment , lecturing was not recorded, and it is hard for the modern audience to understand the meteoric fame of lecturers, which disappeared almost instantaneously with their deaths. However, it would be fair to say that Maria Sanford’s greatest achievement was her lecturing. It was the area in which she gained the most fame, success and money.

Another contributing factor to Sanford’s enormous popularity was her active involvement in civic issues. She preached in Minneapolis churches when they were lacking a preacher, and in 1892 she founded the Minneapolis Improvement League, whose aim was “to beautify and civilize the city.” One of the league’s achievements was to ban spitting in streetcars. From 1892 to 1903 its members distributed flower seeds among the children of the city and awarded prizes each year to the best gardens. The league also worked on improving school facilities by greater parent/teacher cooperation and established the first Pure Water Commission.

Sanford’s involvement with Minneapolis affairs made her very popular locally. In all her battles with the university, the people of Minneapolis stood staunchly behind her and wrote many letters in her defense. They saw her interest as part of her desire to improve the quality of life of those around her and part of her belief in the power of education. It also seems that the eccentricity that took the university so long to adjust to was accepted and respected by the people of the city from the beginning.

When Sanford moved to a new house in 1907, she was troubled by children in her new neighborhood stealing apples from her orchard. Characteristically, she took the matter in hand and bought apple saplings which she sold for pennies to the children, giving them to those who couldn’t afford her low price in return for work in her garden. As she said: “There are plenty of people to love God’s children, so I look after the devil’s.” It was actions like this that made her neighbors vociferous in her defense.

Sanford never married. As a young woman in Connecticut, she broke an engagement because, although the couple went through a period of religious doubt together, they came out on different sides, he an atheist, she a firm but unconventional believer. While at Swarthmore, Sanford had an affair with the president of the college. His marriage and position gave them no option but to curtail their relations, and Sanford’s subsequent heartbreak played a part in her leaving the college.

Throughout her time at the University of Minnesota, Sanford took in students as lodgers. The female students contributed housecleaning toward their board, while male students paid more in rent. Sanford was concerned that the students, especially the women, did not have enough opportunities for recreation and so she encouraged parties and dancing in her house. One of the most unusual sides of Maria Sanford was her financial investments. In the late 1880s she persuaded many of her friends and acquaintances to invest money with some college students who were hoping to profit in the land boom. The bubble burst and an estimated $30,000 was lost. Despite the recommendation of friends such as Governor Pillsbury that she declare bankruptcy, Sanford attempted to pay the money back. Her success can only be measured by the fact that at her death no claims were presented to her executors.

Much of her unconventional behavior can be explained by this debt. She cut her own wood and swept out railway cars for grain for her hens. Her financial problems also shed light on her battle with the university over salary, her refusal to take a sleeper coach when travelling, and her continuation of her profitable lecture career until she died.

After incurring this debt, Sanford involved herself in other speculations, partly to try and pay back the money owing and partly because she enjoyed them. At the age of 74, she purchased

35 acres in Largo, Florida, sight unseen, and was determined to make her fortune growing celery—then a luxury crop. She travelled by train with her spade, a great-nephew, and some celery seed, only to find that the land was covered with palmetto scrub and pine. They lived in a tent for two months while attempting to clear the land, and it was another four months before she abandoned the project and came home to Minnesota.

That same year, the first dormitory for women at the university was built and named after her. This was a great honor and rightly bestowed on one who had d o n e so much for women at the university both by example and in practice.

Sanford was strong-willed and single- minded. All her actions, except her financial dealings, revolved around her fundamental belief in education. Unique in her own time, her theories and practices of education are still uncommon today. Education, she felt, was essential at every stage and in every walk of life. Intellectual progress should be closely linked with moral progress. Too often education was limited to the brief period of childhood, and it was here that her lecturing, civic involvement and extension-school teaching demonstrated various means to keep the adult mind alive.

Maria Sanford thought that formal education was too restricted by methodology and disciplines, with too little emphasis on developing natural gifts, training imagination, and teaching original thought. “Our ideas of education are too narrow and exclusive; we are the devotees of books; we can conceive of no education without them,” she wrote. It was this belief in the necessity of a broader interpretation of education influencing all of life, combined with her natural talents, that gave her power as a teacher.

ADA COMSTOCK (1 877 –1973)

It was Ada Comstock, as the first dean of women at the university, who wrote to Maria Sanford to inform her of the decision to name Sanford Hall after her. Thirty years later she was present as another dormitory was named after herself.

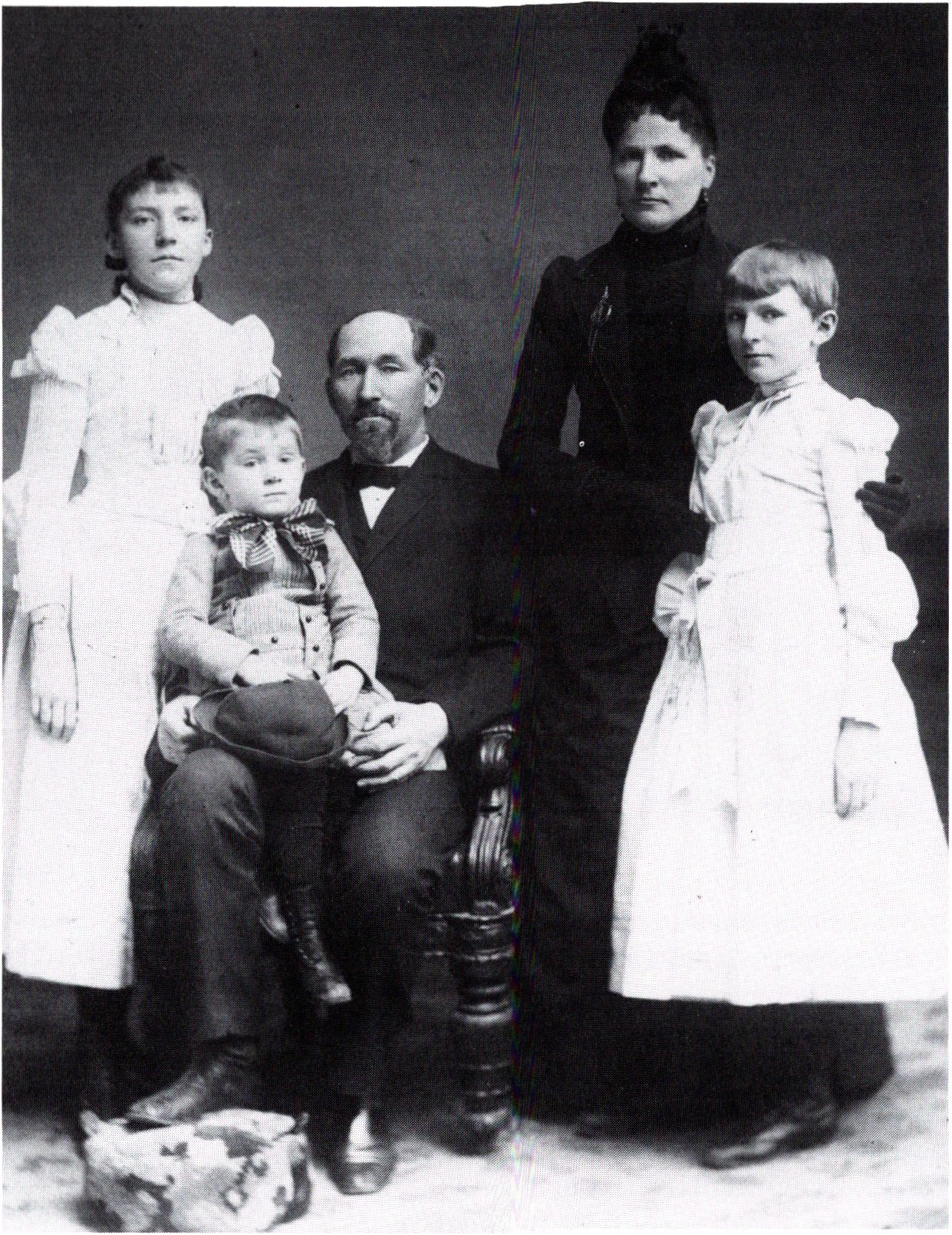

Ada Comstock was born in Moorhead, Minnesota. She was the daughter of Solomon G. Comstock, who was one of James J. Hill’s lawyers. Mr. Comstock served in the state legislature and on the board of regents of the university from 1905 to 1908. He recognized the importance of education, donating land for the norm al school ( teachers college) in Moorhead.

His influence over Ada’s development is clear, as is his devotion to her. As she said: “My father thought I was perfect from the day I was born. My mother had no such illusions.” Although it was her mother who tutored her for eight years, it was her father who took it for granted that she would go to college and, after her high school graduation in 1892, arranged for her to go to the University of Minnesota. Here she lodged with her father’s friend Dean William Pattee.

In 1894 she transferred to Smith College where she took her B.A. In 1899 she got her first job as an assistant teacher of English composition at the university for S225 per year. It is likely that her father’s influence played a role in that appointment, as it did in 1907 when she was appointed the first dean of women at the university. Her chief responsibility was to supervise the ever-growing number of female students.

Ada Comstock (left) as a girl with her family. Her father took it for granted that she would go to college.

In 1912 she became dean of Smith College, a post which she left in 1923 to become president of Radcliffe. There she remained until her retirement in 1943 at the age of 67.

Comstock, like Sanford, was concerned that the female students at the University of Minnesota had too little recreation. She did not seek to provide off-campus alternatives but created social outlets within the university. She founded the Cap and Gown Society and encouraged afternoon teas.

Her major concern was Shevlin Hall. It had been erected in 1906 as a hall for women, but by the time of her deanship just a year later had already begun to deteriorate. When Thomas Shevlin, the hall’s benefactor, donated some more money to the university, Comstock went to President Northrop and asked that it be used to renovate Shevlin Hall. When he told her that it was needed for a new chemistry building, she burst into tears. Luckily, so the story goes, Shevlin’s daughter, a friend of Com stock, passed by the room at that point—and shortly afterward 520,000 was given and Shevlin Hall was renovated. The hall then provided female students with a meeting place, resting rooms, study halls and eating facilities all on campus. They had arrived!

Comstock also advanced Sanford’s concern for the board and lodging of female students, taking the problem from the personal to the university level. She did not take in boarders herself, but rather toured boarding houses near the campus, pronouncing them fit or unfit for female students. The only criteria she looked for were that the house limited itself to female lodgers and that it provided a separate room in which to receive callers.

Although Comstock’s entire career was dedicated to the improvement of education, especially for women, her major achievements were made outside the University of Minnesota. As president of Radcliffe, she walked into an ongoing battle between that institution and Harvard. The latter was protesting the hiring of its professors to teach courses at Radcliffe. Comstock defused the situation, kept hiring Harvard professors, and eventually persuaded Harvard to open its doors to women.

Comstock was more personable on an intimate level than Sanford. Stories about her show her having many close friends and a definite interest in men. While lodging with Dean Pattee, he warned her that she seemed overly interested in young men, an interest that continued into her deanship. Again, unlike Sanford, she dressed well and socialized often. She later said of this period: “For the only time in my life, I was a belle.” A friend of her’s, A.C. Krey, wrote to her years later to tell her that in his first year in the History Department at the University of Minnesota four staff members confessed that they had proposed to her. One of these may have been Wallace Notestein who, although refused, remained good friends with her.

As dean of Smith College, Comstock’s attractive personality made her the confidante of many students. When some of the daughters of her college friends were admitted, she started to be called “Aunt Ada” and decided to move on. Despite the move to Boston, the title followed her, and she became one of the city’s most popular characters. In 1943 she finally succumbed to a 34-year courtship and was married to Notestein in a civil ceremony. The cab driver who drove them to the train station said to his next fare: “Whadaya know! Aunt Ada got married!”

Comstock Hall was built in 1940. Ada Comstock’s work for a social life for female students within the confines of the university, as well as her concern for their living arrangements, more than merited the honor.

Comstock’s life was less single-mindedly focused on educational principles than Sanford’s, and socialization played a far greater role. This was due not only to Sanford’s driving obsession with education, but also to the fact that

Comstock was well-born and never had to struggle for a living. Although definitely advantaged by birth, Comstock succeeded in the end, because she was an intelligent and capable woman with a real interest in education and administration.

ANNA NORRIS (1874 -1958 )

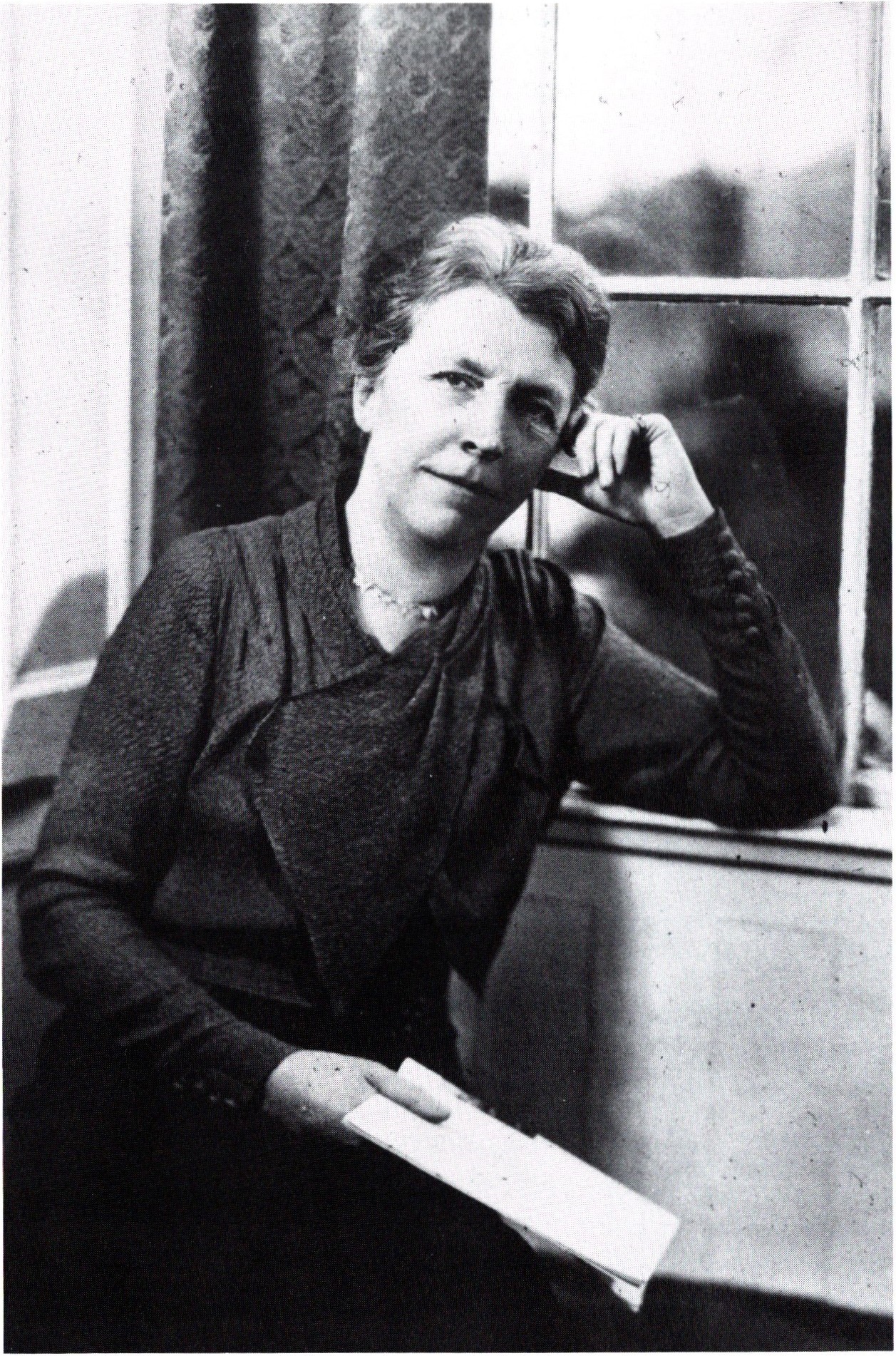

Julia Anna Norris was born in Boston, Massachusetts, and little is known of her childhood or family. She attended the Boston Normal School of Gymnastics, the only such school in the country. She was interested in becoming an M.D. and took her degree from Northwestern University. She taught physical education at the University of Chicago for several years before being appointed assistant professor at the University of Minnesota in 1912. She remained with the university until her retirement in 1941.

When Norris was appointed to the Women ’s Department of Physical Education, it consisted of Norris, a pianist/secretary, and one other teacher. All female students were required to take physical-education classes, and the courses offered included hygiene, Swedish gymnastics, folk dancing, and aesthetic dancing. Most of the female students, however, tried to avoid the requisite classes, because they were held in the armory, with no changing rooms or privacy.

To rectify’ this situation, Norris campaigned for a building devoted solely to women’s physical education. In 1915 the department moved into a new building equipped with a pool, two gymnasiums, and several classrooms. This move permitted the expansion of the curriculum, with the two major additions being swimming and basket ball. The new building and the enlarged curriculum led to a growth in the department and, by the time Norris retired at the age of 66, she headed a group of 12 teachers, 3 part-time assistants, a clerk, and an accompanist, offering a total of 22 courses.

Anna Norris taught physical education at the University of Minnesota from 1912 to 1941.

In 1919 Norris established a teacher training program in women’s physical education. This flourished, and the first class graduated in 1922. In 1933 she personally donated the first of two scholarship funds designed to give annual support to women majoring in physical education.

Norris never forgot her medical background and used it wisely through out her career at the university. When first appointed, she insisted on a physical examination of her students, stressing the importance of this both to monitor progress and to avoid accidents. Initially, she brought in doctors to perform the physicals. She felt, however, that the university needed its own medical team, for this as well as other services. Norris thus campaigned for the establishment of a student health service. Once it was established, she happily turned over to it the responsibility for athletic physicals, a role it still fulfills today.

Anna Norris, like Maria Sanford and Ada Comstock, was much respected outside of the university. Unlike them, however, she remained within her discipline of physical education. Her aim was the same: to enhance and gain respect for the education of women. She was the co-founder of four professional organizations, including the Women’s Division of the NAAF, an organization originally intended to keep unethical and immoral behavior out of men’s sports. In 1923 she was invited to Washington, D C. by Mrs. Herbert Hoover. The President’s wife, acting as one of the three vice- presidents of the NAAF, realized that ethical concerns also affected women’s sports. In the founding of the Women’s Division, Anna Norris was appointed to draw up a list of 16 resolutions. These resolutions later served as the basis for monitoring women’s sporting events worldwide.

Norris had a great interest in travel. She was in Europe in 1914 when war broke out and was told about it by a Belgian soldier while visiting the Leaning Lower of Pisa. She had problems getting home, because no one would honor her $400 of traveler’s checks. And when she finally made it to Paris, she sat on her suitcase as train after train was mobbed by anxious people trying to get out of Europe. Finally, she was helped onto a train by an Englishman and so made her escape.

The only hint of romance in her life was a series of summers spent horseback riding in Yellowstone Park with a man described only as her good friend and an official park guide. One summer, her horse lost its footing, and she was saved from being thrown down the mountain by a grove of trees. Her courage in the face of peril so impressed her companion that the peak in question is now officially known as Mount Norris.

In the 1930s, she decided to experiment closer to home and bought a 40-acre tract of land in Anoka. This land was unusual because it supported various arctic flora and fauna. When she died, she left this land to the university.

These few anecdotes are all we know of the private life of Anna Norris. It seems that she shared with Sanford a sense of isolation. This was certainly felt by Norris’s staff with whom she remained aloof. Both Norris and Sanford seem to have made a conscious decision not to develop their personal lives for fear of sapping their professional energies.

When Anna Norris retired in 1941, it was proposed that the gymnasium for which she had worked so hard nearly 30 years earlier should bear her name. In her acceptance letter, she wrote: “The women’s gymnasium seemed like a dream fulfilled when it was first built. It became a second home to me in which 1have worked long and happily.”

LOUISE POWELL (1871 -1943 )

Louise Powell was born in Staunton, Virginia. Due largely to the influence of her maternal grandfather, who was a superintendent in a hospital for the insane , she studied nursing in Richmond. After practicing nursing for nine years, she entered the Teaching College at Columbia University. There she was recommended to Dr. Richard Beard, founder of the University of Minnesota’s school of nursing. He invited her to become the school’s second director, which she did in 1910. In 1924 she left to become dean of Western Reserve University’s school of nursing. It is a tribute to her that she was always offered positions; never once did she apply.

The University of Minnesota’s school of nursing offered the first university teaching for nurses in the world.

The University of Minnesota’s school of nursing offered the first university teaching for nurses in the world. In 1919 Powell designed a graduate degree program for nurses, and in 1922 her successes w ere acknowledged when many local hospitals closed their nursing schools, making the university the central school of nursing in the state.

Louise Powell as a young nurse

Louise Powell (center) surrounded by the University of Minnesota nursing class of 1912- the first university- trained nurses in the world.

Like Sanford and Comstock, Powell was very concerned about the living accommodations of her students. She complained that there were two nurses per room, that the closets w ere in another part of the building, and that there were 10 nurses to each bathroom and only one sitting room for 33 people. “It is a nerve-wearing, absolutely unfit way for women who are being subjected to the nervous strain of nursing 56 hours in each week to be housed,” she wrote. She also felt that the housing conditions w ere unfair, because the nurses were collectively giving 7,400 hours per year to the hospital and paying $150 each per year for their education and accommodations. In 1933, nine years after she had left the university, a dormitory for nurses was built and named after her. When the building was demolished in 1981 to make room for the new University Hospital, there were complaints for two reasons: first, that the architectural beauty of the building was all too rare on the campus and should be preserved; and second, that the name of Powell should remain honored for her work in nursing education.

VERNA SCOTT (1876 -1964 )

Verna Golden was born in River Falls, Wisconsin. After graduating from high school, her family sent her to Leipzig, Germany for four years to study music. There she met Carlyle Scott, whom she married. In 1902 Mr. Scott was appointed to teach music at the University of Minnesota. In 1919 Mrs. Scott was appointed director of the University Artists Course, a position she held until 1944. She was also manager of the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra from 1930 to 1938.

In the 1918-19 academic year, the Women’s Faculty Club had put on a minstrel show to raise money for dormitory furnishings. Mrs. Scott was the primary organizer, and when the event was successful, she proposed an annual event from which half of the profits would go to the music department for scholarships and half to the Club. Despite the initial success, there was hesitation about risking the money, and finally Mrs. Scott obtained a personal guarantee from President Marion Burton.

Unfortunately, the first year of the new Artists Course was nearly the last. Scott had attracted a famous German opera singer to be the star and, to make the evening even more memorable, had required that the audience w ear evening dress. The night of the performance, she set off by car in a white satin gown with her children and an ice pitcher and an oriental rug to be used as props. Crossing the 10th Avenue bridge, her car caught fire, but deter mined Mrs. Scott and party started to trudge on through what was becoming a fairly heavy snowfall. A passing taxi stopped to her hail, and the door opened to reveal her star, the singer who, according to the Minneapolis Tribune, “seeing the disheveled woman before her … shrieked to her driver to drive on.”

Continuing to walk toward the armory, Scott was finally given a ride and arrived to find an angry audience standing in full evening dress in the snow outside the locked doors. The situation gradually defused as people were let in and an apologetic singer, realizing her earlier mistake, did her best to pacify them with words and music. The concert was a success, and the next year the Artists Course continued with Scott as paid manager and with its own funds created from a third of the profits.

The series enabled university students to hear world-renowned musicians at a very low price. Scott’s leadership combined both her insight as a musician in knowing whom to invite, her skill in persuading them to come, and her determination in making the event a success. W hen a German pianist displayed his artistic temperament by refusing, at the last minute, to go on stage, she grabbed him by the lapels and told him, in Germ an, to stop his nonsense as there were 2,500 people waiting for him. He blanched and rushed on stage, and it was only afterward that Scott realized that her German had failed her, and that the pianist had rushed out to what he thought was the audience of his lifetime, 250,000 people!

Like nearly all the other w omen included in this article, Scott fought a battle over buildings. When Northrop Auditorium was being built, she passed by the construction site and saw that the stage they were installing was much too small for concerts. She complained to President Coffman, who told her that nothing could be done as they had no funds to change anything. She then went to her friends in the state legislature, and the stage was built to her specifications. The move to Northrop Auditorium allowed the University Artists Course to be expanded to include dance, and Scott’s greater time involvement led her to demand and obtain an increase in salary.

Scott had always involved herself in music for the community as well as for the university. She instituted a “Down town Series” for the city of Minneapolis, and in 1930 she was approached by the president of the Orchestral Association and asked to accept the post of manager of the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra. Due to her appointment, the orchestra was allowed to use Northrop Auditorium as its permanent home—a melding of civic and academic institutions that was as successful as it was unusual.

With this combination of positions, Scott essentially ran the music program in the Twin Cities for several decades. During this time, she managed to book such talented artists as Sergei Rachmaninoff, Yehudi Menhuin, and George Gershwin. She continued to run her “ Downtown Series” after retirement and also lectured for several years. One of her recurring complaints was that she received too much attention while her husband, who built the Music Department at the university, received too little. She felt this was slightly rectified when the music school was named after both of them, and the Minneapolis Tribune commented: “Scott built the school. Mrs. Scott brought world-famed musicians to the students and the city at large.”

RUTH BOYNTON (1896 -1977 )

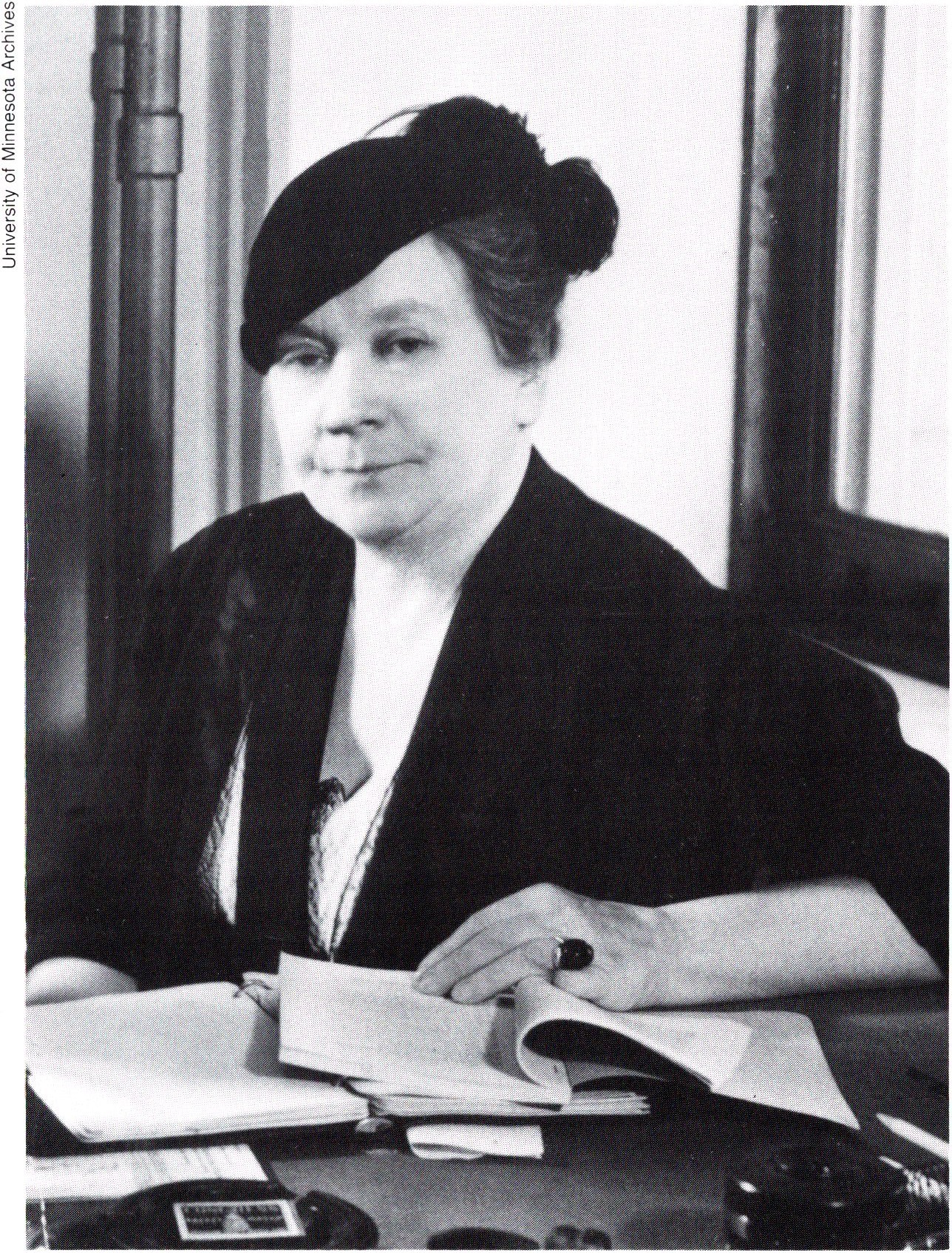

Ruth Boynton w as born in LaCrosse, Wisconsin. In 1921 she graduated as an M.D. from the University of Minnesota and the next year became the first female doctor at the University of Minnesota Health Services. In 1927 she took a position as professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, b u t was n o t happy there. In 1931 she returned to the University of Minnesota and to the health service. In 1936 she w as appointed director – the only female director of a co-ed college health service in the country, a distinction she continued to hold for over a decade.

Boynton’s career is distinguished by her single-minded devotion to the University Health Service. Her connection to it went back to 1918 when the brand new health service found itself tried by the Spanish Flu epidemic. Boynton —one of 2 ,000 students who contracted the disease who was collected by the health service’s Model T and taken to recuperate in a nearby fraternity house.

Because the university was founded before Minnesota became a state, the university was -and is- able to claim a degree of autonomy from the state involvement. One of the main areas in which this partial autonomy has had an effect is public health. As a result the university- rather than the state- has authority over public health matters on campus. It w as Boynton w ho initiated the development in this area, creating a position for the first full-time college

In 1936, she was appointed director— the only female director of a co-ed college health service in the country.

health educator in the country and establishing a department of environmental health and safety.

One of Boynton’s major concern was tuberculosis. She did studies on the incidence of TB and the effectiveness of hygiene and screening in controlling the disease. She expanded the use of the Mantoux test by demanding that all news students received it. In response to claims from students that they caught TB from the staff, she persuaded the board of regents to institute obligatory- physicals with Mantoux tests for all new non-academic staff. In 1941 this requirement was extended to include all new academic staff. Thus, she broadened health service, transforming if from a student health service to a university health service. Outside of the university, Boynton stayed with her defined interests — student health, public health, and TB. She was president of the American Student Health Association from 1940 to 1941 and was involved with the Minnesota State Board of Health.

As an employer, Boynton demanded and received respect and dedication from her staff. Despite her apparently hard-nosed approach, her staff members say that she w as not difficult to work for. It w as always possible to predict what she would do in any circumstance: the best thing for the health service. In 1973, after a fifth floor was added to the health-service building, it w as suggested to the board of regents that the completed health service be named after its long-serving director. This was done in a dedication ceremony in 1975 which Boynton attended.

All of these women were people of great determination and ability. Not only did they succeed in their chosen fields, they also triumphed in, and were honored by a mainly male institution. It is true that teaching w as considered acceptable for women, but that did not stop discrimination. Their salaries were lower than their male counterparts. Smith College approached President Vincent regarding Comstock’s appointment before asking her. And the military refused to use Powell’s nurses in World War I and instead asked her to train their men.

The determination needed to succeed had to be great, and it affected private lives. Only Scott and Comstock married, and Comstock’s marriage coincided with her retirement. Although sexism was not the active issue for them that it is today, there were some recognition of the problem. Comstock wrote in a letter after her marriage, “I’m convinced that the superior achievements of men is due in p art to their refusals . . . to be distracted by concern for clothes, food, housekeeping and all the rest.”

At the same time, their femininity did sometimes work in their favor. It is hard to imagine a man crying, as Comstock did, when refused money, and even harder to see it being effective. Victorian chivalry, still very- much alive, allowed Sanford’s eccentricities of manner to go unpenalized, although her eccentricities of teaching did not. The women were also advantaged by being pioneers. Female involvement at the university was relatively new, and they were able to make their names shaping and directing that involvement rather than trying to excel within previously defined strictures.

The university does not show any consistency in the naming of its buildings. These women spent differing lengths of time in Minnesota, and their contributions varied enormously. This is due, in part, to the arbitrary nature of the award: the university could not build a building for every worthy woman. It was also not above the influence of money. Shevlin Hall, named after Alice Shevlin, was so called at the request of benefactor Thomas Shevlin, Alice’s husband. Despite these limitations, the buildings chosen do reflect the individual women’s concerns while at the university.

Finally, all these women were active at the university during the decade 1909-19. To what extent can we see the extent can we see the influence of the “best-loved woman in Minnesota,” Maria Sanford, on their careers? Is it possible that the university’s experience of her encouraged her successors to flourish as they may not have done otherwise?

Dr. Ruth Boynton served as director of the University Health Service (now called Boynton Health Service) from 1936 to 1961.