May 13, 2021

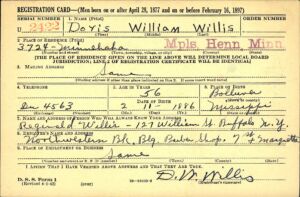

Dorsie Willis draft registration. Ancestry.com. Mr. Willis was a Minneapolis resident for more than 60 years.

A few weeks ago, I got a research request for anything regarding a man named Dorsie Willis, someone I knew nothing about. It wasn’t unusual that I didn’t know anything about Mr. Willis – I learn a lot about the history of Hennepin County through research requests. This was just another opportunity to learn. And I have always found people with 2 first names (for first and last) to be intriguing.

The researcher’s email described Mr. Willis as “one of 197 Negro soldiers in US Army’s 25th Battalion dishonorably discharged. Based on claims several of them shot up the town of Brownsville, TX, including killing one man.” This happened in 1906. Even now I’m still trying to make sense of that. It does not make sense.

This researcher had done a lot of…research on the circumstances surrounding the dishonorable discharge to discover that the town of Brownsville, TX didn’t want an African American battalion stationed there and essentially rigged a riot in which one of their own was shot and killed, then blamed the death on the very presence of the Black soldiers. President Theodore Roosevelt dishonorably discharged Not 1, but 167 Black soldiers for the death of the Brownsville citizen without a trial. Roosevelt didn’t discharge the White officers in the same barracks. These officers actually supported the soldiers’ statements, even adding that the soldiers were hunkered down in barracks avoiding gunfire so they couldn’t have shot anyone.

This is still mind-boggling. But why am I writing about this man who was discharged from the US Army in 1907? Well, according to the researcher, Dorsie Willis was the last survivor from that battalion, and he lived in Minneapolis. It bothered me that there was no information in the archive about him. Nor was there information in other local historical institutions’ digital collections. I searched our directories first to see where Mr. Willis lived and found that he lived in Minneapolis as early as 1915. In fact, he lived in 7 different places between the years 1915 and 1937, making a living as a porter, a barber, a janitor, and a shoe shiner, whatever he could do to make money for his family.

Dorsie Willis was a husband and father at the time of his discharge. It must’ve been difficult to find work in this city as a Black man, let alone one who had been discharged from the army at 20 years of age. He could be found sweeping up at barbershops downtown such as P.H. Timmins and Arvid N. Swensen’s barbershops downtown in the 30s and 40s. Later in his life, he shined shoes in the Northwest Bank building, one of his last places of employment.

Even after he was discharged from the Army, he registered again for the draft of WWII. As you can see, there is a “U” in front of the number on the card, which meant it was an “old man” number. He still registered to fight for his country even after being treated with such disrespect. His signature is also on his son Reginald’s draft card.

In November of 1973, with the help of Rep. Don Fraser, and Hubert Humphrey, Dorsie Willis received an honorable discharge from the United States Army along with a check for $25K. Mr. Willis commented that “If that’s the best we can do, it’s the best we can do. It doesn’t make up for what happened to me, but it’s better than nothing.” Humphrey had requested “pension and reasonable compensation” for Mr. Willis in the amount of $40K in February of 1973.

I would like to have known more of Dorsie Willis’s story. Learning about him through city directories, census records, and news articles, he seemed a resourceful and charismatic person, who would have had a better life without the damage done by dishonorable discharge and the racism of his time.

I know there are more stories like this, involving BIPOC members of our community that are just waiting to be illuminated. Even a small thread to pull on is better than no thread at all, or better than nothing, as Mr. Willis put it. For HHM to tell more stories like this, we need more records, more photos, more documents from the communities of color in Hennepin County. It’s HHM’s mission to “collect, preserve and share Hennepin County history to educate, enlighten and inspire” this community and the world.

Mr. Willis lived on Minnehaha Ave from 1937 until he died in 1977 at the age of 91. At the time of his death, he was the last survivor of the “Brownsville Incident.”

There have been a couple books written on the “Brownsville Incident,” or “Brownsville Affair” as it has been called. The Brownsville Raid by John D. Weaver written in 1970 was the publication that brought attention to the treatment of the Black soldiers and brought about a new investigation of the case. The army did indeed find the troops innocent in 1972.

Sources

“Brownsville Affair.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., www.britannica.com/event/Brownsville-Affair.

“The Brownsville Incident.” TR Center – Brownsville Incident, www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Learn-About-TR/TR-Encyclopedia/Race-Ethnicity-and-Gender/The-Brownsville-Incident.aspx.

McConagha, Al. (1973) “HHH asks compensation for ex-soldier in city” Star Tribune Wednesday, Feb. 21, 1973

(1973) “House approves $25,000 for local black veteran” Star Tribune Wednesday, Nov. 17, 1973

Written by Michele Pollard, Archivist at Hennepin History Museum