April 7, 2021

Minneapolis Morning Tribune, October 22, 1918

The influenza pandemic of 1918 created tense disagreements in Minneapolis and perhaps no man found himself caught in the middle more so than Dr. Harry Guilford. Serving as the city’s health commissioner, Dr. Guilford led Minneapolis’s response to the crisis. He was quick to act when the first case of the flu was reported in early October and began to prepare for the worst-case scenario. He proposed that all the beds at City Hospital (now known as Hennepin County Medical Center) be dedicated to patients with influenza, anticipating the virus’s rapid spread. Dr. Guilford encouraged the public to wear masks constructed from at least six layers of cheese cloth. He also spoke to institutions such as the draft board about the realities of the virus, calling it the “most dangerous in the nation’s history.” He sought to answer questions about the virus and its transmissibility, explaining that primary spread was through person-to-person contact. He also explained that the most effective ways to combat the virus were through good hygiene and avoiding public spaces, discrediting opportunists who marketed products such as laxatives as “cure-alls” for the disease.

As October progressed, it became clear that the measures taken so far by Dr. Guilford and other Minneapolis health officials were not enough. Many Minneapolis hospitals struggled to care for the number of patients being admitted not only due to the sheer volume, but also because many doctors and nurses were serving in Europe at the close of World War I. The Minneapolis Morning Tribune explained “So many physicians and surgeons have gone to Europe or to training that those at home have more than they can attend to comfortably and to good advantage.”

In reaction to the worsening situation, Dr. Guilford proposed to close most public spaces beginning on October 12. This included schools, movie theaters, restaurants, and churches. However, this decision (which was a more aggressive approach than other cities) received criticism and skepticism from some members of the public. Lines of people crowded vaudeville theaters and other entertainment venues in anticipation of their closing. A group of ministers convinced Dr. Guilford to amend his decision to close churches completely to allowing them to remain open at 25% capacity. Dr. Guilford even received criticism from colleagues such as H.M. Bracken, a leading flu expert in Minnesota, who originally said on closures: “If you begin to close, where are you going to stop?” However, as the death toll began to climb Dr. Bracken ultimately agreed with Dr. Guilford’s decision.

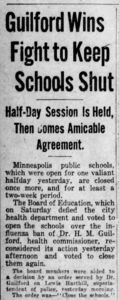

The most dramatic disagreement with the public played out between Dr. Guilford and the Minneapolis School Board. Led by Henry Deutsch, a lawyer, the School Board voted to open classrooms on Monday, October 21 in direct violation of Dr. Guilford and the city of Minneapolis’s order. Deutsch argued that Dr. Guilford did not have the authority to close the schools and that children should be allowed to go to school because they most typically did not get a severe case of the virus (the population most prone to complications and death were young adults due to how the virus interacted with the immune system). However, Deutsch neglected to realize that although children did not get seriously ill themselves, they were still capable of spreading the virus to their teachers, families, and other members of the community.

In response to the vote, the Minneapolis Department of Health issued a strong statement that read, “Anyone who disregards the definite orders of the health department will be brought to justice. The direct snapping of fingers of the board of education in the face of the health department is a matter that requires the attention of the courts. We intend to use the police force if necessary.” Deutsch and the School Board opted to disregard this warning and Minneapolis schools opened on October 21 as normal. However, this decision did not last and in the afternoon of October 21 after a meeting between Dr. Guilford, Lewis Harthill, the superintendent of the Minneapolis police force, and the School Board they voted to close the doors again. The only person who voted against closing the schools was Henry Deutsch.

Minneapolis schools and other public places reopened on November 15 but were quickly closed again when a second outbreak surged through the community. On December 30, schools were reopened a third time with precautions implemented by Dr. Guilford such as setting a quarantine period of ten days after a child was sick with the flu to prevent a third outbreak.

By spring of 1919, influenza cases and deaths in Minneapolis started to drop back to average numbers. However, the flu never disappeared and different strains of influenza continue to infect people around the world today. Presently, health professionals are more equipped to combat diseases through increased medical knowledge, vaccines, and other treatments. Despite medical advances, medical professionals still don’t completely understand what made the 1918 influenza so deadly. Research on the 1918 virus continues as medical professionals seek to understand the epidemics and pandemics of the past to better protect the world in the future.

Author Bio: Hannah Dyson is a research assistant at the Hennepin History Museum. A graduate of Augsburg University, she is passionate about Minnesota and American history and plans to pursue a graduate degree in museum studies.

Sources

“Are To Wear Masks On Trip To The Camp.” The Daily People’s Press. October 17, 1918. https://newspapers.mnhs.org/jsp/PsImageViewer.jsp?doc_id=5f69c51e-37c1-4b61-87f8-d953db38d341%2Fmnhi0031%2F1I7PNR5B%2F18101701.

Brown, Curt. Minnesota 1918: When Flu, Fire, and War Ravaged the State. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2018.

“Churches Are Divided on Reopening Sunday.” Minneapolis Morning Tribune. October 19, 1918. https://newspapers.mnhs.org/jsp/PsImageViewer.jsp?doc_id=addabf07-f848-43e3-a488-2782562f220d%2Fmnhi0005%2F1DFC5G5B%2F18101901.

“Clash Over School Order Due Monday.” Minneapolis Morning Tribune. October 20, 1918. https://newspapers.mnhs.org/jsp/PsImageViewer.jsp?doc_id=addabf07-f848-43e3-a488-2782562f220d/mnhi0005/1DFC5G5B/18102001.

“Draft Boards Tackle Problem of Epidemic.” Minneapolis Morning Tribune. October 19, 1918. https://newspapers.mnhs.org/jsp/PsImageViewer.jsp?doc_id=addabf07-f848-43e3-a488-2782562f220d%2Fmnhi0005%2F1DFC5G5B%2F18101901.

“First Aid in Influenza Prevention.” Minneapolis Morning Tribune. October 22, 1918. https://newspapers.mnhs.org/jsp/PsImageViewer.jsp?doc_id=addabf07-f848-43e3-a488-2782562f220d/mnhi0005/1DFC5G5B/18102201.

“Guilford Wins Fight to Keep Schools Shut.” Minneapolis Morning Tribune. October 22, 1918. https://newspapers.mnhs.org/jsp/PsImageViewer.jsp?doc_id=addabf07-f848-43e3-a488-2782562f220d/mnhi0005/1DFC5G5B/18102201.

“Schools Reopen Tomorrow After Seven-Week Ban.” Minneapolis Morning Tribune. December 29, 1918. https://newspapers.mnhs.org/jsp/PsImageViewer.jsp?doc_id=addabf07-f848-43e3-a488-2782562f220d%2Fmnhi0005%2F1DFC5G5B%2F18122901.