Brought to Light: The University of Minnesota’s heritage of slavery

by Christopher P. Lehman

This article was originally published in Hennepin History Magazine, Spring-Summer 2016, Vol. 75, No. 2.

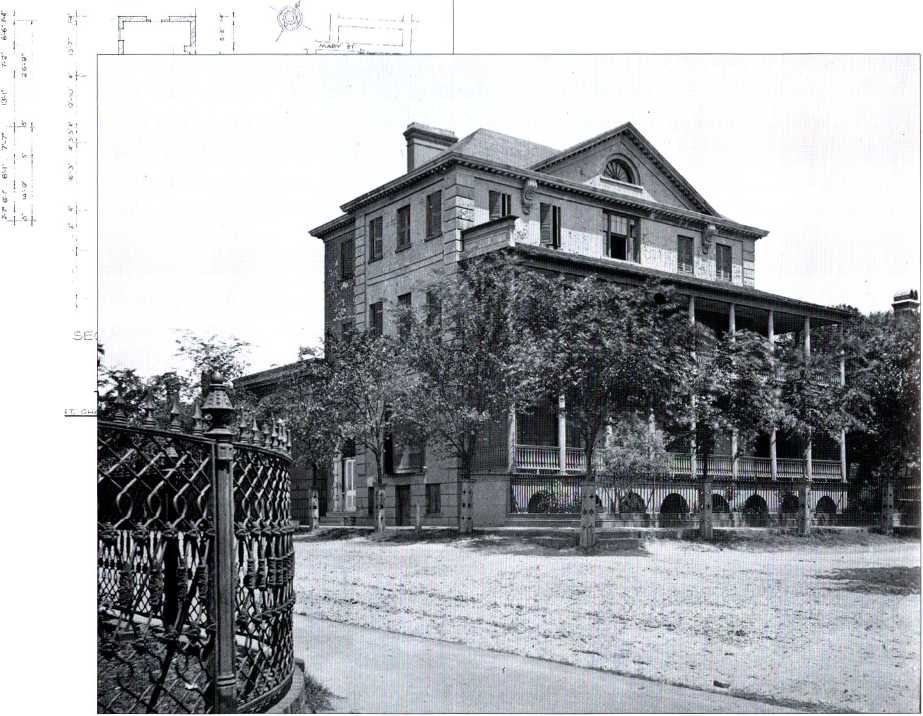

The grand, stately William Aiken House of Charleston, South Carolina, is an unofficial and extremely distant part of the campus of the University of Minnesota. Capital earned by the labor of hundreds of African American slaves on William Aiken Jr.’s plantation comprised a significant portion of the university’s finances in the late 1850s and early 1860s. Plantation owner Aiken noticed the university in an impoverished and dormant state during a visit to Minnesota in 1857, and he immediately lent thousands of dollars to the institution. At that time Minnesotans expressed their gratitude for Aiken’s support, but since the War Between the States pitted Minnesota against South Carolina, writers have omitted record of his contribution from their histories of the university.

Nevertheless, Aiken’s loan was a rare act of cross-sectional cooperation between the South and the North during a time of increasing national discord over the extension of slavery into fledgling states in infancy like Minnesota. Also, Aiken’s gift shows that a university in the Northwest was reliant on wealth from a southern plantation’s unfree labor, not unlike the Ivy League schools of the colonial era and the southern antebellum schools.1 From the early 1850s, southerners had come to Minnesota for business, recreation, or both. Advancements in steamboat travel enabled vessels to travel between Minnesota and Louisiana during the spring and summer months, when the Mississippi River was free flowing. Wealthy southerners with political connections invested in large portions of land in Minnesota. Buying land while on vacation and returning to the South in the fall with real estate deeds in hand, these men became absentee land- owners. Kentucky’s Sen. John Breckinridge and Tennessee state senator William Stokes were among them. Some investors, such as Harwood Iglehart of Maryland, chose instead to live permanently in Minnesota while retaining ownership of their slaves in their home states, though these were few and far between.2

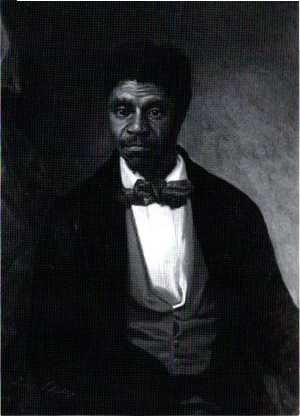

Dred Scott (1795-1858). The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in his case freed plantation owners to travel north without giving up their slaves.

After March 1857 southerners had even more incentive to travel to Minnesota. That month the U.S. Supreme Court’s verdict in Dred Scott v. Sandford legalized slavery in all territories, and Minnesota was still about 14 months short of statehood at the time. Newspaper reporters took note of an immediate rise that summer in the number of slaveholding sojourners to the Northwest, and they called attention to people who elected to stay permanently in Minnesota with their slaves. One slaveholding migrant in Stillwater specifically claimed that Dred Scott legitimized his actions.3

In the early summer of 1857, William Aiken Jr. of Charleston, South Carolina, was part of that post-Dred Scott southern influx to Minnesota. He had just completed nearly 20 years of public service—in offices ranging from South Carolina’s legislature and governorship to the U.S. House of Representatives— and suddenly had the time to travel at length. Like other tourists of means, he lodged at the Fuller House, an opulent hotel in St. Paul. From there he took a short trip to visit the Falls of St. Anthony. The falls were a popular, cooling tourist attraction for southerners suffering from summer heat. As a result, the location proved ideal for entrepreneurs to capitalize on its popularity.4 The University of Minnesota was one enterprise benefiting from the location of the falls, though the educational institution was not much to look at in 1857. It had open for some time. Construction of the sole building on campus cost more money than the university’s facilitators possessed, and the extended period of construction exacerbated the institution’s debt. The building was not even completed before the university opened in 1851, and it remained unfinished in 1857.’’

When Aiken saw the school, he immediately took pity on it. He advanced between $ 15,000 and $20,000 of his own money to the institution, and he purchased $8,000 in university bonds. It was the largest sum of money given by an individual to the university to that time. Moreover, through his loan, Aiken became the school’s principal  benefactor.6 As a rich planter, Aiken could afford such generosity. He held more than 700 slaves on his vast plantation. He had a reputation among Charleston’s slaves as a master who was not abusive, but he profited handsomely from their labor.

benefactor.6 As a rich planter, Aiken could afford such generosity. He held more than 700 slaves on his vast plantation. He had a reputation among Charleston’s slaves as a master who was not abusive, but he profited handsomely from their labor.

He spent $13,000 yearly to maintain his plantation but annually sold $25,000 worth of goods produced by the slaves. The slaves took care of more than 200 livestock animals and grew 2,000 bushels of corn and 4,000 bushels of sweet

Aiken visited the Falls of St. Anthony (upper left in 1855), about the time E. Whitefield sketched the drawing “from Cheever’s Tower.”

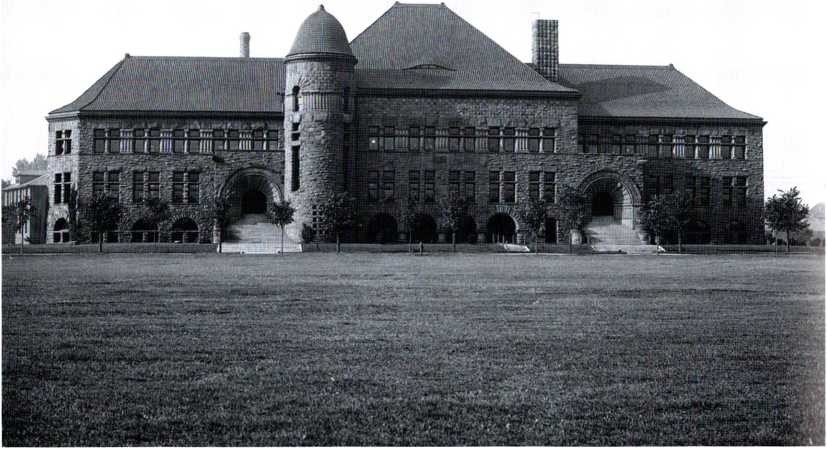

potatoes annually. The master quartered his slaves in plain, wooden houses, reserving an enormous Gothic Revival mansion for himself and his family.” Aiken’s donation helped to expand and resurrect the university. Builders added a fourth floor to the lone campus building in late 1857, and a local newspaper grandly predicted: “This edifice will be one of the most magnificent granite structures in the whole north west.” The school reopened in 1858. The New York Herald saw Aiken’s interest in northwestern investment as a gesture of intersectional goodwill. A writer for the newspaper expressed hope that such purchases between the North and the South would decrease feelings of sectionalism or “dissolution excitement,” as the periodical put it.8

Meanwhile, Aiken’s investment proved a short-term solution to the university’s problems, for it gave the university only a brief respite from dormancy. Because it did not receive enough funding from tuition fees to remain open, the institution operated for just six months in 1858 before closing again. Further, the donor was the victim of unlucky timing. His loan predated national financial calamity—the Panic of 1857—by just a couple of months. The economic recession began the next fall and lasted well into 1859, putting potential for the university’s reopening in jeopardy. As a result, Aiken’s loan was jeopardized, too.10

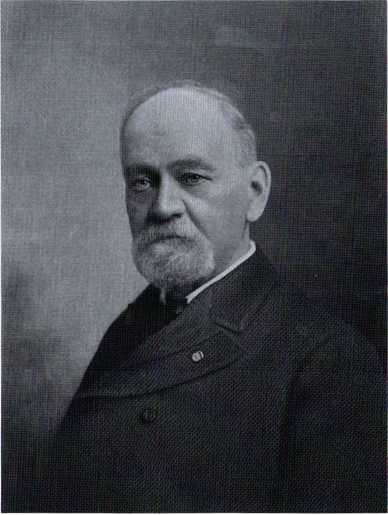

The country’s emergence from the economic panic did not help the school; in fact, it made embarrassing national news for hemorrhaging money via construction. The completion of one wing of the campus building cost $49,000, but two-thirds of the edifice was yet unfinished. “This costly structure is going to ruin, no care being taken of the premises,” complained one reporter, “all the doors being wide open, and the snow has drifted into the building and melts on warm days through the floors.” Aiken’s hometown newspaper called the facility “a melancholy ruin.”11 The university remained in Aiken’s debt well into the 1860s, but that durable financial cross-sectional connection could not prohibit war from erupting between the North and the South. Americans had been bitterly divided over slavery since the Kansas- Nebraska Act’s nullification in 1854 of the federal government’s three-decade prohibition of the “peculiar institution” in northern territories. At about the time Mitchell’s article appeared, Pillsbury initiated the erasure of Aiken from the university’s history. He facilitated the board’s report to the governor’s office, recalling the misfortunes of the school’s first decade and the triumph of its latest reopening. The report credits the commission for the university’s success without praising it so boldly as did Mitchell. Still, Pillsbury and the rest of the board did not even mention Aiken in their discussion of the university’s early years.14

“John S. Pillsbury initiated the erasure of Aiken from the university’s history.”

After the 1860s, those telling the story of the beginnings of the University of Minnesota focused exclusively on the facility’s financial woes and of its rescue by Pillsbury and the commission. “Saved by John S. Pillsbury” was the heading Willis West chose when writing about the school’s salvation. John B. Gilfillan dubbed Pillsbury “the most devoted friend and generous giver the University has had.” E. B. Johnson’s Dictionary of the University of Minnesota gave Pillsbury the prestigious title “Father of the University.” Upon Aiken’s death in 1887, Minnesota’s newspapers paid tribute to his political career but said nothing of his philanthropy to the state’s university.15

The slaveholder remains absent in the writing of today. When the new millennium began, Stanford Lehmberg and Ann M. Pflaum devoted three pages to Pillsbury but none to Aiken in their book The University of Minnesota: 1945-2000. Within the past two years, books by Chaim M. Rosenberg and Iric Nathanson have identified only Pillsbury as a school savior. In addition, the website for the university’s archive yields no results from a search for Aiken’s name.16

The omission of Aiken removes not only a central donor from the school’s history but also the crucial role of slave labor in the facility’s survival. If unfree African Americans had not generated the planter’s wealth, he would not have possessed the funds to assist the institution. Moreover, despite the university’s woeful condition upon Pillsbury s arrival in 1863, Aiken’s do nation (his loan was never repaid) helped improve it to the point at which Pillsbury and his fellow regents could still save the school. The University of Minnesota lives today thanks in no small part to hundreds of slaves on a plantation in Charleston.

References

- See Craig Steven Wilder, Ebony and Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities (New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), for a detailed study of colonial-era American colleges and their relationships to African American slavery.

- Frank H. Heck, Proud Kentuckian: John C. Breckinridge, 1821-1875 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1976), 50-51; Christopher P. Lehman, “The Slaveholders in Lowry’s Addition,” Crossings 41, no. 6 (Dec. 2015-Jan. 2016): 14; Christopher P. Lehman, “The Slaveholders of Payne-Phalen,” Ramsey County History 50, no. 4 (Winter 2016): 23- 24; U. S. Census, 2nd Ward, St. Paul, Ramsey County, MN, p. 145; U. S. Slave Schedule 1860, Annapolis, Anne Arundel County, MD, p. 4; Anne Arundel County Manumission Record: 1844-1866, 832, p. 198. See also Steven James Keillor, Grand Excursion: Antebellum America Discovers the Upper Mississippi (Alton, MN: Afton Historical Society, 2004), for detailed information on the importance of the steamboat to the Northwest.

- “Slavery in Minnesota,” Bradford Reporter, June 25, 1857, p. 2; “Our Minnesota Correspondence,” New York Herald, July 16, 1857, p. 2.

- “Our Minnesota Correspondence,” New York Herald, July 4, 1857, p. 8; William D. Green, A Peculiar Imbalance: The Fall and Rise of Racial Equality in Early Minnesota (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2007), 91.

- B. Johnson, Dictionary of the University of Minnesota (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1908), 9-12.

- Columbus Crisis, 9, 1862, p. 84; Rlantor- ville Express, Sept. 10 1857, p. 3; Third Annual Report of the Board of Regents ofthe State University to the Legislature of Minnesota (St. Paul: Wm. R. Marshall, 1863), 7; W. H. Mitchell, “The State University,” Minnesota Teacher and Journal of Education 2, no. 5 (Jan. 1869): 164-.

- S. Slave Schedule 1850, St.John’s Parish, Charleston, SC, pp. 8-18; Henryjames, Notes of a Son and Brother: A Critical Edition (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2011), 312; Maurie D. Mclnnis, The Politics of Taste in Antebellum Charleston (University of North Carolina, 2005), 208-209.

- MantorvilleExpress, 10,1857, p. 3; Willis M. West, “The University of Minnesota,” in The History of Education in Minnesota, John N. Greer, ed. (Washington: GPO, 1902), 96; “Our Minnesota Correspondence,” New York Herald, Jul. 16, 1857, p. 2.

- “What Does It Mean,” New Orleans Daily Crescent, 27, 1857, p. 5; “Where They Invest,” Freemans Champion, Aug. 13,1857, p. 2.

- B. Johnson, Dictionary of the University of Minnesota, 13; Willis M. West, “The University of Minnesota,” 96; John B. Gilfillan, An Historical Sketch of the University of Minnesota (State Historical Society of Minnesota, 1905), 21-22; James L. Huston, The Panic of 1857and the Comingof the Civil War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 1987), 262; Charles W. Calominis and Larry Schwei- kart, “The Panic of 1857: Origins, Transmission, and Containment)”Journal of Economic History 5, No. 4 (Dec. 1991): 808-810.

- Baltimore Daily Exchange, 30, 1859, p. 1; Evansville Daily Journal, Apr. 11, 1859, p. 3; Charleston Mercury, May 4, 1859, p.2.

- Columbus Crisis, 9, 1862, p. 84; Theodore Christian Blegen, Minnesota: A History of the State (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1963), 251.

- Willis M. West, “The University of Minnesota,” 98; W. H. Mitchell, “The State University,” 164-66.

- The Annual Report of the Board oj Regents of the University of Minnesota to the Governor of Minnesota for the Year 1868 (St Paul: Press Printing, 1869), 6-7.

- Willis M. West, “The University of Minnesota,” 98; John B. Gilfillan, An Historical Sketch of the University of Rlinnesota, 41, 169; “Ex-Gov. Aiken Dead,” Paul Daily Globe, Sept. 8, 1887, p. 4; St. Paul Western Appeal, Sept. 17, 1887, p. 2; Mower County Transcript, Sept. 14, 1887, p. 6.

- Stanford Lehmberg and Ann M. Pflaum, The University of Minnesota: 1945-2000 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001), 414; Chaim M. Rosenberg, Yankee Colonies across America: Cities upon the Hills (Lanham, MD: Lexington, 2015), 99; Iric Nathanson, The Rlinnesota Riverfront (Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2014), 62.

Christopher P. Lehman is a professor of ethnic studies at St. Cloud Slate University. He is the author of Slavery’s Reach: Southern Slaveholders in the North Star State (Minnesota Historical Society, 2019) and Slavery in the Upper Mississippi Valley (McFarland, 2011).