Twin Cities’ black golfers have a legacy of fighting discrimination

by Tina Burnside

This article was originally published in Hennepin History Magazine, Summer 2018, Vol. 77, No. 2

Charles Rodgers started playing golf at age five in his hometown of Memphis, TN, because his mother played golf. Rodgers spent many days on the golf course playing and as a caddy. However, because of segregation, blacks were not allowed to play at white golf courses, though some courses allowed blacks to play occasionally. “They let the kids play, but not adults. They did it as a one-shot deal to try to show they weren’t prejudiced,” said Rodgers, 66, who moved to Minneapolis in the 1970s to attend graduate school at the University of Minnesota.1

Golf and the Professional Golfers Association (PGA) have had a long history of racism where African American golfers were excluded from golf courses, tournaments, and membership. From 1934 to 1961, the PGA had a “Caucasian only” clause in its bylaws that prevented blacks from membership. Even after the PGA removed the “whites only” clause, a 1990 survey revealed that at least 17 clubs, that were sites for PGA tour events, had all-white memberships.2

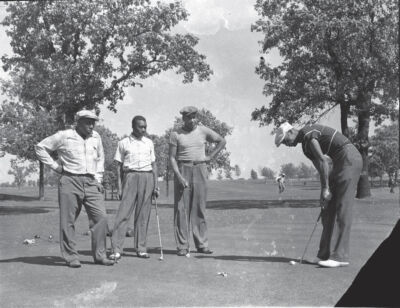

Golfers William Barry, far left; and man putting has been identified as either Jim Tucker or Wilbur Dugas. 1940s

Minnesota was not immune to the PGA’s “whites only” policy, and blacks were prohibited from competing in local golf tournaments. As a result, in 1931, Jimmie Slemmons, a Minneapolis resident, founded the Twin City Golf Club as an association of black golfers. Slemmons created the Minnesota Negro Open golf tournament in 1939 to give blacks an opportunity to play and compete. The tournament was renamed the Upper Midwest Bronze Amateur Tournament and attracted participants from around the country. Former heavyweight champion Joe Louis won the tournament in 1957.3 Slemmons, who passed away in 1983, stated in interviews that he started the club because blacks could not join golf clubs, which prevented them from establishing handicaps and competing in tournaments. He said black golfers were not explicitly told they could not join clubs but instead were given various excuses, including that membership was full. Slemmons also complained that blacks could not use the golf course club locker rooms or the clubhouses for meetings.4 The Twin City Golf Club and Upper Midwest Bronze Tournament are still in operation today.

Minneapolis golf professional Solomon Hughes was a top-rated player on the United Golfers Association (UGA) tour. Founded in the 1920s, the UGA was a national association for black golfers, and it sponsored the National Negro Open, which Hughes won in 1935. Hughes grew up in segregated Alabama and learned to play golf by caddying. In 1943, Hughes moved from Alabama to Minneapolis, but despite his status as a professional golfer, no public courses or private country clubs in Minneapolis would hire Hughes as a golf pro. He joined the Twin City Golf Club and taught golf lessons. Hughes was also a leader in integrating the Hiawatha Golf Course clubhouse. In 1948, Hughes submitted applications for himself and fellow African American golfer Ted Rhodes, who was also a top-ranked golfer, to compete in the St. Paul Open tournament, which was a PGA event sponsored by the city’s Junior Chamber of Commerce (Jaycees). The St. Paul Open rejected Hughes’ and Rhodes’ applications because they were not members of the PGA — and they could not be members because they were black. The Minneapolis Spokesman, an African American newspaper led by editor Cecil E. Newman, blasted the St. Paul Open for race discrimination. Hughes was rejected again in 1951 despite the Jaycees opposition to the PGA’s exclusionary rule. Finally, in 1952, Hughes and Rhodes were accepted to play in the St. Paul Open after the PGA faced protests led by Joe Louis in San Diego, and the PGA permitted a few black golfers to play in PGA tournaments.5

Black golfers have fought to integrate golf clubs and courses, and recently a group of black golfers rallied to stop the Minneapolis Park Board from closing the Hiawatha Golf Course. The course was scheduled to close in 2019 due to groundwater pumping, which exceeded the Department of Natural Resources (DNR) permit. Supporters organized the “Save Hiawatha 18” group, and black golfers argued that the course should remain open due to its historical significance as one of the first Minneapolis golf courses that allowed blacks to play, thus integrating its clubhouse. The Minneapolis Park Board voted to delay the course’s closing for five years.6

Rodgers said that while certain golf courses in Minnesota excluded blacks, the Hiawatha was welcoming. Rodgers recalled that at some golf courses, blacks were always looked at as “suspicious,” and they were forced to play evening tee times because the white members did not want to associate with them. Rodgers joined the Twin City Golf Club in 1980 when he went to Hiawatha Golf Course and saw a group of black golfers playing. Rodgers said the Twin City Golf Club provided a community for black golfers, and the Bronze tournament was special. “At one point, we had 5,000 people attending the tournament. It was an entire weekend of events that brought people together.”

Trophy winners at the Bronze Amateur Golf Tournament. Theodore ‘Ted’ Allen, center; James W. ‘Jimmy’ Slemmons, right. 1940s.

Dorothy Hines, 95, was also a member of the Twin City Golf Club and played in several Bronze tournaments and won some trophies. Hines said she started playing golf over 60 years ago when her son was a caddy as a teenager. “I would take him and his friends to the golf courses to caddy so they could earn extra money,” Hines said. “He encouraged me to learn to play, and I started by putting and hitting into the net in my backyard.”7

Rodgers said despite golf’s history of excluding blacks and trying to keep the sport a “white boys’ club,” blacks have excelled. But Rodgers is concerned about the waning interest of black youth in the sport. “Some kids see it as ‘dumb’ . . . chasing a white ball around the course,” Rodgers said. “But it’s a great sport at teaching patience, and there are opportunities for scholarships that can help kids go to college.” Rodgers is a golf coach at South High School in Minneapolis and teaches individual lessons at Hiawatha Golf Course. Rodgers said the Twin City Golf Club also has a junior league and tournament. Rodgers encourages youth to get involved with the First Tee of the Twin Cities golf program, which provides education and life skills through learning to play golf. In Minneapolis, Hiawatha, Columbia and Gross National golf courses have First Tee programs. “Golf allows you to make connections that you normally may not,” Rodgers said. “It can open doors and opportunities.”

References

1. Interview with Charles Rodgers, March 28, 2018.

2. Diaz, Jaime. “Racism Issue Shakes World of Golf.” New York Times, July 29, 1990.

3. Holbert, Allan. “Golf.” Minneapolis Star Tribune, July 13, 1975; “The ‘Bronze’ is back!” Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder, August 13, 2016.

4. Holbert, Allan. “Golf.” Minneapolis Star Tribune, July 13, 1975; “Jimmie Slemmons, Bronze Open golf promoter, dies at 71.” Minneapolis Star Tribune, April 26, 1983.

5. Jones, Thomas. “Caucasians Only: Solomon Hughes, the PGA, and the 1948 St. Paul Open Golf Tournament.” Minnesota History Magazine, Winter 2003–04.

6. Mahamud, Faiza. “Black golfers rally to note historical significance of Hiawatha Golf Club.” Minneapolis Star Tribune, August 16, 2017; Mahamud, Faiza. “Hiawatha Golf Club closure to be delayed at least five years.” Minneapolis Star Tribune, October 6, 2017.

7. Interview with Dorothy Hines, February 3, 2018.

Tina Burnside is a civil rights attorney and writer in Minneapolis. She is co-founder of the Minnesota African American Heritage Museum and Gallery.

Photos by John F. Glanton, courtesy of Hennepin County Library and the Children of John Glanton. John Glanton took hundreds of photographs of the African American community of Minneapolis–St. Paul in the late 1940s. See the collection online at digitalcollections.hclib.org.

Double Exposure: Images of Black Minnesota in the 1940s — The Photography of John Glanton, Hardcover, 8×10, 160 pages, 200 b&w photos, $29.95

The photographs included in this article are featured in the book Double Exposure: Images of Black Minnesota in the 1940s — The Photography of John Glanton, published by the Minnesota Historical Society Press in October 2018. A native of Minneapolis, John F. Glanton was a prolific photographer of African American life in the Twin Cities during the late 1940s and early 1950s. After serving in World War II, Glanton returned home and began taking his camera around the streets, parks, clubs, restaurants, and private homes of the city. His photos offer a rare look into the lives and lifestyles of families and individuals often left out of histories of Minnesota’s past, revealing a dynamic community at a time when the nation was entering the postwar boom but before the national civil rights movement had taken root. The images highlight black-owned businesses, athletes, the music and club scene, and weddings and other family occasions to depict the experiences of African Americans as presented through the lens of an African American photographer. Long forgotten in the garage of a family member, the photo negatives were recently rediscovered and digitized by the Special Collections of the Hennepin County Library. A selection of 200 photos are featured in the book, along with commentary that further illuminates the experiences of African Americans in postwar Minnesota.