Samantha Majhor. Photo by Dr. Kasey Keeler.

by Michele Pollard

Ȟaȟá Wakpádaŋ Bassett Creek Oral History Project

Since the summer of 2020, Hennepin History Museum archive has seen an increase in oral history donations. Perhaps there has never been a better time to check the pulse of one’s community and really find out what people are thinking. Oral histories are valuable resources for communities, families, and individuals. They have a way of making history come to life, adding color and nuance to an otherwise black and white event that might have only been a date on a page.

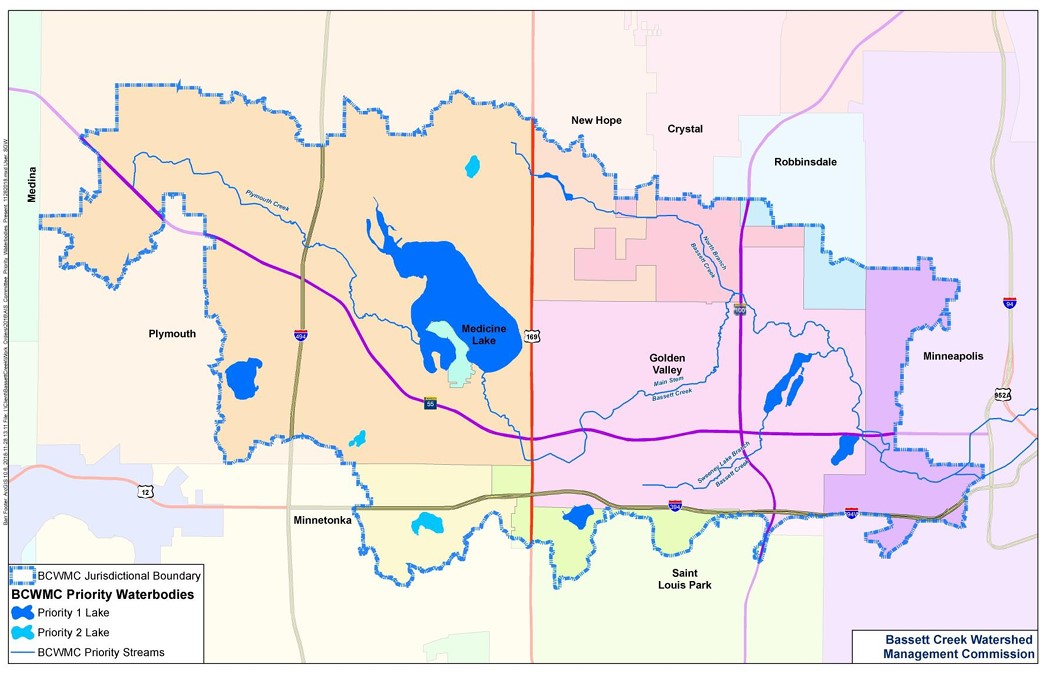

One oral history project we received earlier this year was the Ȟaȟá Wakpádaŋ / Bassett Creek Oral History Project. In 2021, Valley Community Presbyterian Church (VCPC) in Golden Valley, sought to act on the land acknowledgment they had worked on for almost a year. The project’s narratives address lived experiences in the Ȟaȟá Wakpádaŋ watershed, including Golden Valley and other Minneapolis suburbs and help fill in the gaps with respect to suburban life for American Indian people in the Ȟaȟá Wakpádaŋ / Bassett Creek watershed.

Dr. Kasey Keeler. Photo by Larry Johnson.

Dr. Kasey Keeler, a professor from the University of Wisconsin, interviewed fourteen American Indian people from the West Metro whose tribal backgrounds include Dakota, Anishinaabe, Ho-Chunk, Assiniboine, Lakota, Odowa, Ponca, and Zuni.

Keeler, who is an enrolled tribal member of the Toulumne Band of Me-Wuk Indians and a descendant of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, grew up in Crystal.

The project was funded in part through the Minnesota Historical and Cultural Heritage Grant Program, with additional funding and support from VCPC and the University of Wisconsin Center for Community and Nonprofit Studies. Read more about the events and projects around the VCPC land acknowledgment at https:// www.valleychurch.net. The following is an excerpt from the Ȟaȟá Wakpádaŋ / Bassett Creek Oral History Project interview of Samantha Majhor by Kasey Keeler:

KK: So, if I’m hearing this correctly, your family came to the Bassett Creek area to work for Belgarde Properties, which is a Native company? The family is Turtle Mountain Ojibwe? And it’s headquartered here in the Twin Cities?

SM: Yes.

KK: Wow.

SM: The patriarch who started the company, Charles Belgarde, passed a couple of years ago, and now his sons and daughters own the company, particularly his son, Ken Belgarde, runs the company. My mom has worked with them for… I remember she had her twenty-fifth-year anniversary not too long ago, but it’s been more than twenty-five years now.

KK: Wow, this is so exciting. I want to learn more about Belgarde Properties, but this also shows me that your mom must really especially like her job if she’s been there for twenty-five years and has been able to advance.

SM: She loves it. She just has an amazing work ethic. But also, I think it’s because the company was sort of family oriented. She came in as maybe the least paying, lowest rung on the ladder and worked her way up. They’re a company that really promoted from within. And for the time, a young woman in what must have been the early 1990s, and at that point she was a single mom, to have a company that was supportive of her and really gave my sister and I opportunities. They had at that time several apartment buildings across the Twin Cities. The one that we ended up at, within this Minnetonka-Plymouth area, it put us in a really great school district that I don’t think we would have otherwise been in. It really shaped our lives.

KK: That’s wonderful, and actually leads to the next question. So where did you attend school in this region? And when you were in K[indergarten] through twelve schooling, did you attend or were you involved in an Indian Education program?

SM: The first one I went to in this region or area… I think they all ended up being in the Wayzata School District. I went to Sunset Hill [Elementary], I went to East Junior High, and then I went to the Wayzata High School, which is a little bit further out, sort of moving west, even more into the suburbs and away from the city. And what was the other part of the question?

KK: Did you participate in an Indian Education Program?

KK: Did you participate in an Indian Education Program?

SM: I did not. So, in my family, my dad is enrolled at Fort Peck in Montana. I am not enrolled. And the thing is, like many Native families, there was a lot of disconnect. We had early deaths in my family. We do have the boarding school history in my family, so a lot of our history and connection to Fort Peck or just our ancestry was severed in a lot of ways. My grandfather was sent to boarding school out in Oregon, so far away from where he was born, and he died very young. So I would say growing up, my family connection and knowledge to our Native ancestry was slim. But I had an uncle, my dad’s older brother, who became the family historian. And he connected with a lot of relatives that my dad and his brothers didn’t know about growing up, connected to folks who were still out in Oregon by Chemawa Boarding School, and we learned more and more about our history. And I think as the oldest grandchild I inherited that interest and the family knowledge and have expanded on it in just the work that I do. In my specialties in Native American literature, I was able to take Dakota language when I studied at the University of Minnesota and have learned so much more that explains the absence of knowledge in my family. So, I really understand now what I didn’t understand growing up in the Minnetonka-Plymouth-Golden Valley area, where I knew I was Native. I had been told that in my family. I knew my grandpa was Native, but I never met him. He passed away young. I grew up in a place, I would say a space where the Native community, we’re writ large on place names in Minnesota and certain parts of history, but a lot of it is hidden, especially in these spaces outside of the Twin Cities.

KK: Right, absolutely. Growing up did you know any other Native families? I know you mentioned the Belgarde family that your parents worked for, but beyond that?

SM: Beyond that, I really didn’t. Even in school, I can’t remember anyone identifying as Native or talking about it a lot. And I think like many students still in American education, you learn a very shallow bit of Native history and Native people are almost exclusively historicized. So not in a present tense sense. Belgarde was a connection as far as knowing Native people. I would also say, I spent a lot of time at my grandma’s house in the Black Hills. And so it was interesting growing up, sort of in this very, I will say, white suburban space, and then having summers and vacations when I would go and spend a lot of time in Rapid City and the surrounding areas and I remember feeling there… Because I take after my dad. I have darker eyes and darker hair and sometimes, you never know how people are going to read you. But sometimes I get the question like, “What are you?” So I know I’m a little bit of a mystery as far as how people read me. I think in some, certainly in some circles, I’m very white passing. And then in other circles, there’s this question of like, “What are you? Are you Native? Are you Latina?” So, I don’t know. But I grew up with my mom, who is mostly Dutch and Norwegian in heritage, blonde haired, blue eyed. My sister was blonde haired, blue eyed, so I kind of stood out. And when I would go to Rapid City, I would see people who looked more like me. And so that was big. You know, Rapid City was a space where I felt a little bit more connected to the Native community. And when I would come home, to Minnesota and these suburbs, I always felt a little different.

KK: So, as a Native person, particularly as somebody who identifies as Dakota, when you think about Bassett Creek or the Ȟaȟá Wakpádaŋ watershed, how do you relate to this region as a Native person, if at all?

SM: I think, again, it’s like my family history. I now know so much more and make so many more connections, just because of my course of study and the work I’ve done to sort of reclaim a lot that was lost in these assimilative programs. One of the things that I think about growing up and behind the apartment buildings where I lived, we were friends with a little group of young girls in the neighborhood. And there were always these marshy areas behind our neighborhood that we would go and sort of have little play clubs and things like that. And so there was this little bit of connection to these waterways that run through these suburban spaces.

But much of the suburban space, I mean, it’s commercialized. I lived right by Ridgedale Mall, which was, at that time, one of the biggest malls, and when we were teenagers, we were there all the time. And I think everything in both suburban and urban spaces orients us away from a lot of these waterways and natural resources that surround us. So, it’s like you almost have to kind of sneak away, like your children, kind of taking the off the beaten path in order to connect with them. I mean, we have fabulous parks in Minnesota. But even that, if you’re driving, if you’re just moving around the space, we are continually oriented away from noticing this part of the world around us. Now I’ve done a lot of work thinking about the Mississippi River watershed, and so when I think about the Bassett Creek watershed and that space that I grew up in, I think about how invisible it was to me and how important it is when we do think about it, and that we need to think about it. That it is connected to this big network that’s basically, if you look at the watershed of the Mississippi [River], it’s the lungs of this continent. And so it’s that dichotomy of it being so invisible in the way we live in that space, but so significant as far as how it connects to this huge system. It’s interesting to think about now, because now I’m aware of it. But growing up, I wasn’t.

KK: I hear so many similarities to my own experience, Sam. Growing up in the suburbs, particularly Coon Rapids as a Native person, and realizing there is some sort of connection. But as a young Native person who is red or white passing, it’s something you don’t really think back upon until you’re a little bit older, particularly in our fields of study. As adults, we are able to more clearly reflect upon the significance of that.

So, kind of on the flip side then, as a Native person growing up in a very Dakota place, but that is also a very white place, how did growing up in a predominantly white suburb influence how you have thought of your identity both past and present?

SM: Yeah. Well, like I said before, growing up, it was this sense of always being a little bit different, but not having this part of my identity really recognized. I remember being really young and having a particular teacher, and we must have been doing some type of Native American unit. This is funny to me, where we were thinking about Native American oral stories. And then we were asked to write a story emulating Native storytelling. And I wrote this story, and in my mind, if I were to put it into a region, it would be like, Southwest Native American, because I learned about the weaving that they do in the Southwest. And so, I totally ripped off Cinderella and put it into this Native setting. Like, it’s so kind of bizarre now. But I had told my teacher, “Well, I’m Native.” And so, I think for her it lent this authenticity to it, but I was totally ripping off Cinderella, and just giving it this Native vibe. It’s so interesting to look back on that moment and then think about what were the other students writing, too, in this kind of an assignment. But it’s like, there are those little moments where I was trying to connect to my heritage, but without guidance and without knowledge. It remained a mystery to me in so many ways. Those small connections when I would go to Rapid City and just see more, and my grandma really worked hard to take us to museums and did her best to take us to powwows, [and] try and connect us in the ways that she could as a non-Native person, but it was a real mystery. And then I was trying to find it in literature. I was an English major, took Native classes every opportunity I could get, which wasn’t often.

I would say it was really getting into Dakota language that transformed things for me, and at the same time, I was able to learn more about my own family history and connect it with the history of Minnesota and where my relatives were at the time of, for instance, the 1862 Dakota War. Why did I have family… How did they go from Minnesota to Standing Rock [Reservation]? It was tracing that and putting those puzzle pieces together, but learning the language.

So again, I graduated from Wayzata. In our senior yearbook, it has a whole front page about the word “Wayzata,” which is based on a Dakota word Waziyata, which means north or northward. And that’s probably one of the first Dakota words I learned because it was in our high school yearbook. But later on, learning the language, you just realize that in this space Dakota language marks the land in so many ways, and no one [or] so few people know that they’re already speaking Dakota language, and that these Dakota place names, they describe the land. So, [it’s] unlike what you see in a lot of Western tradition where places are named after people, okay? So, I think we were talking about Bassett Creek. Bassett was someone who had settled. They’re a significant person. Well, this is very common in the Western tradition.

In Dakota tradition, and many Native traditions as far as place names, it is a description of the place itself. And I think that’s really significant in shedding light on the way that we look at place, at landscape, at environment, and our relationships to it in a very different way. For Ȟaȟá Wakpádaŋ you have “little river” or “little creek” [as the English translation for “wakpádaŋ”], I would say, so Bassett Creek makes sense. Ȟaȟá means with “little falls” or like a churning of water, or sort of disturbed water or bubbling falls, you might call it. It describes that place rather than naming it after somebody. And when we think about these little things in the language, when you start noticing how our grammar works, and how we name places, how we connect places and describe them, that you really get the cultural philosophy and that relationship to place. So Waziyata, “northward.” Minnetonka/Mni Tanka, “big water,” so connected to the lake there. All of these things describe the Dakota view of the place, and then oftentimes is in connection to [Dakota knowledge]. You could go on and expand upon, what are these places in memory? What seasons were they visited and connected to in different ways? How do people live there? Our language carries that knowledge.

————————————-

All the transcripts can be accessed on the MN Collections platform in the Hennepin History Museum collection.

There’s also a Ȟaȟá Wakpádaŋ / Bassett Creek Oral History Project podcast with content from these interviews on Spotify and Youtube.

BARB SOMMER is a local author who has also been an oral historian for more than 30 years. She and co-author Mary Kay Quinlan created The Oral History Manual to guide those interested in conducting oral histories. Sommer and Quinlan have recently completed the book’s third edition. In it, they provide guidelines for projects of different scale, and offer a framework for planning, budgeting, and processing recorded data, taking the reader from zero to oral historian in just over 150 pages.