From the Magazine: Country Life in the Suburbs: The Story of Spruce Shadows Farm

By Cynthia de Miranda

This article was originally published in Hennepin History, Spring 1999, Vol. 58, No. 2

Advertisements for Spruce Shadows Farm from Minnesota Guernsey News

Less than 50 years ago, Bloomington was a quiet place populated by working farms. Postwar development, however, catapulted the rural township into a thriving suburban city in a few short decades. Yet, in the shadow of Bloomington’s intense commercial growth, sheep still graze in the pastures of a farm that has resisted the suburbanization crowding around it. Spruce Shadows is more than a farm, however. It is one of the few surviving country estates built by prominent Twin Cities families seeking refuge from urban life. The trend began long before Spruce Shadows was established in the 1930s; it is, in fact, nearly as old as the Twin Cities themselves.

Early Suburbanites

In the 1860s, new arrivals to the Northwest frontier moved into the burgeoning commercial districts of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, both on the Mississippi River. A few made fast fortunes and within a decade began escaping the cities on weekends and in the summer, traveling by private carriage to estates they built in the country. (1)

For the head of the household, the weekend home often served as much a diversion from business as a retreat from the city: many “country gentlemen” had hobby farms and raised livestock at their estates. In fact, the farm often predated the summer home. This was the case at Lyndale Farm, established by Col. William King, a Minneapolis pioneer, politician, and newspaperman who lived with his family on Nicollet Island. King bought an expanse of land near Lakes Calhoun and Harriet in the 1870s, when Franklin Street marked the city’s southern limit and the lakes were still part of rural Richfield Township. King raised racehorses and prize-winning cattle at Lyndale Farm, and he eventually converted a bunkhouse into a summer home for his family, maintaining the Nicollet Island house as a permanent residence. A decade later, James J. Hill, Saint Paul’s famed railroad builder, established the North Oaks Stock Farm ten miles north of Saint Paul. Hill carried out experiments in livestock breeding and crop testing at North Oaks, which grew to encompass 5,000 acres. Like King’s farm, North Oaks became the Hill family’s summer home. (2)

Bloomington was another attractive option for escaping the city. The rural township spread southward from Richfield to the Minnesota River and offered dramatic views from the bluffs. Twin Cities businessmen Charles E. Wales and Marion Savage each established an impressive estate there. Both men, in keeping with the township’s agrarian character, kept livestock—Wales raised cattle and Savage trained racehorses—and both built summer homes. Waleswood included a Colonial Revival mansion complete with bowling alleys, a swimming pool, and a ballroom. Savage’s house, perched on a bluff overlooking his farm, featured a huge rounded porch. From there, he could time his horses racing on the track below. (3)

Country living remained popular with some prosperous urbanites well past the turn of the century. An example from the 1920s is Green Acres Farm in Cottage Grove, established by Saint Paul businessman Roger B. Shepard. In keeping with the country lifestyle adopted by their counterparts, the Shepards commissioned local architect Thomas Holyoke to build both their summer home and the farm’s outbuildings. Holyoke’s design for the farmstead was a conscious reflection of vernacular forms developed on working farms. With its parallel rows of connected barns and outbuildings, Green Acres recalls the traditional architecture of New England farms. (4)

A few made fast fortunes and within a decade began escaping the cities… traveling by private carriage to estates in the country.

American Country Living

The willful retreat of Twin Citians to the country was neither new nor unique. Ancient Romans kept city houses and country estates; centuries later, English nobility consciously imitated the Romans’ lifestyle as well as their architecture. In 18th-century America, Washington and Jefferson were gentleman farmers, as were 19th-century business leaders like James J. Hill. The popularity of the country lifestyle grew in the United States, and, in the first years of the 20th century, a new magazine emerged to chronicle this genteel way of life. Country Life in America pledged in its inaugural issue to “portray the artistic in rural life.” As if to justify its existence, the monthly periodical noted that, in the first two years of the 20th century, nearly half a billion dollars had been invested to develop “suburban” property outside the country’s 28 largest cities. “We believe we also have an economic and social mission,” the magazine stated. “The cities are congested; the country has room.” The eclectic range of topics covered in the magazine’s articles and advertisements-from choosing poultry and cattle breeds to selecting gowns for formal occasions-indicated that the intended audience was not the average American farming family. The magazine theorized that “the city may not satisfy the soul,” offering instead not just the country but the country complete with sculpture for the garden, antique French furniture, and great golf shirts. (5)

Historical antecedents and popular magazines may have inspired well-off Twin Citians to retreat to the country, but many who did so were not far removed from the farm in the first place. Colonel King, for instance, worked as a farmhand and wagon driver before getting into politics and the press, and James J. Hill grew up on a Canadian farm. (6)

While the gentleman farmer rarely ran the agricultural operations, he often involved himself to some degree. Such men were, in fact, seen as leaders in agricultural development. Country estates generally employed more progressive agricultural techniques or equipment than did a typical farm, mainly because the estate owner, who did not make his living from the farm, could afford to experiment. In her study of Hill’s North Oaks Farm, Garneth Peterson has noted that “leadership by such ‘gentleman farmers’ was highly significant [in Minnesota]. In the late 19th century, a period before scientific agriculture when efforts of the University to teach agriculture were held under suspicion by practicing farmers, prosperous men such as Hill and William S. King of Minneapolis, provided leadership for their less well-off contemporaries.” (7)

The former Marion Savage Home (later the Masonic Home) in Bloomington, 1927

Barns at King’s Lyndale Farm in 1881, now Dupont Avenue South and approximately 38th Street in Minneapolis

James E. Kelley, circa 1917. Minnesota Historical Society

This trend was not limited to the state. In the early 1930s, Country Life characterized the “country gentleman” as “the man behind the pure-bred industry. His support made possible the establishment of the breeds in England and their maintenance in America and elsewhere. The dairy cow owes its present unequalled state of efficiency to him.” (8)

Spruce Shadows Farm

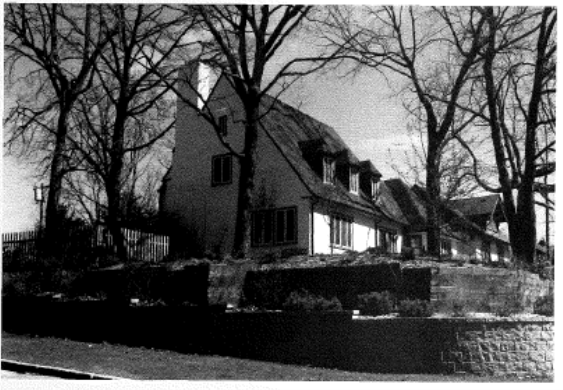

In most respects, Spruce Shadows followed the lead established by earlier Twin Cities country estates. Its stoneclad house and farm buildings show attention to architectural style, and surrounding acreage was used for progressive agricultural pursuits. One important distinction, however, was that Spruce Shadows was, from the start, a year-round home. The farm occupies a picturesque site on the north bluff of the Minnesota River. Post-and-rail fencing rings the farm fields and pastures, and a thick grove of trees shrouds the main house from view. The Colonial Revival house, clad in locally quarried limestone, overlooks the Minnesota River to the south. Impressive stone chimneys with brick trim rise from the north and west sides of the house, and similar brick detailing highlights the many windows that punctuate the south façade. A matching garage is linked to the house by a breezeway. (9)

Across a pasture southwest of the house, three barns dominate the farmyard. The smallest is a sheep barn, clad in limestone that matches the house, while the two others appear to be dairy or cattle barns. Animal pens fill the space between the two wood-dad cattle barns. Other outbuildings in the yard housed animals or stored feed or equipment. Most buildings, like the two cattle barns, are wood-framed structures with horizontal wood siding. East of the stoneclad sheep barn, however, is another building sheathed in limestone. The small, square structure, topped by a ventilator, may have been a milkhouse. The last two structures at the farm are a second house and garage. The house, smaller and simpler than the main house, features a symmetrical Cape Cod design.

The walls are covered with wood shingles painted white. Like the main house, a nearby garage is linked to the house with a short breezeway. Bloomington Township still consisted largely of farms in the first half of the 20th century. While country estates dotted the rural township at the time, only a few urban expatriates had, like the Kelleys, opted for full-time residence there. Improved roads enabled a daily commute from Bloomington to downtown Saint Paul, where James Kelley worked. (10)

Kelley came to Saint Paul from lumber camps in northern Minnesota, where he had worked for a year after completing high school in Ashland, Wisconsin. He studied at the Saint Paul College of Law (now William Mitchell College of Law), and received his degree in 1917. After two years in the army, Kelley returned to Saint Paul and began his professional career. He became a prominent attorney and businessman, maintaining a private practice with Gerhard Bundlie (who was elected mayor of the capital city in 1930) and acted as general counsel of the Hamm Brewing Company.

Throughout his professional career, Kelley was also involved with several local businesses, including United Properties, Northland Insurance, and Industrial Credit, and sat on the boards of a number of educational and charitable organizations. (11)

In 1923, James married Margaret Hamm, and the couple eventually settled into a house near Mississippi River Boulevard in Saint Paul, just a block from the river. Although their neighborhood was set apart from the city-isolated by the river and the lack of streetcar access—the Kelleys apparently wanted a more authentic version of country life than East River Road could offer. In 1932, the family purchased acreage in east Bloomington on the Minnesota River bluffs, and it had moved there permanently by 1933. (12)

At Spruce Shadows, Kelley established himself as a breeder of Guernsey cattle, selling bulls and calves from the Bloomington farm for more than 20 years. Spruce Shadows also produced prize-winning milch cows: one cow set a state record for milk production in its class in 1945. Kelley became heavily involved with the Minnesota Guernsey Association, serving as its president in the 1940s and continuing on the board of directors until the early 1950s. He advertised Spruce Shadows Farm regularly in the association’s monthly publication and hosted the Twin Cities District Parish Show in the summer of 1948. (13)

Despite his obvious interest in the workings of Spruce Shadows, Kelley did not supervise the day-to-day operations on the farm. Instead, he employed a manager and herdsman to oversee the farm and sometimes enlisted the advice of a consultant for assistance with the herd. The farm’s manager is listed as a “resident manager ” in 1956; presumably, he lived in the smaller house west of the cattle barns. The size of the herd topped 100 head of cattle by 1959, which may have been too much for the farm to accommodate. In 1958, Kelley purchased land near Stillwater and established the Kelley Land and Cattle Company. Sometime after the purchase, he apparently moved the cattle from Bloomington to the Stillwater farm, which encompassed 2,900 acres in 1997. There Kelley also raised pheasants and had a gun range for sportsmen. (14)

The variety of livestock buildings at Spruce Shadows indicates that Kelley did not restrict himself to cattle. Kelley’s obituary verifies that fact, indicating that livestock at the farm included Duroc hogs and White Holland turkeys. Kelley, in fact, is credited in the obituary as bringing White Hollands to the state. Crops grown at Spruce Shadows have included turnips, hay, corn, and soybeans; the fields currently provide pasture for sheep. The sheep barn and the combination poultry house and livestock shed have apparently been at the farm since before 1937, a good indication that the Kelleys maintained a diverse holding of livestock after establishing the farm. (15)

If the exemplary operations of a country gentleman’s farm tagged him as such, then the architecture of his farmstead provided similar clues to the true nature of the farm. “The architectural design of country estate buildings is the outstanding characteristic that distinguishes them from the purely utilitarian structures erected by the often misnamed practical farmer, ” was the informed opinion of Country Life in a 1929 article. (See below for information on Magnus Jemne, credited by the Kelley family as the architect responsible for Spruce Shadows buildings.)

Crops grown at Spruce Shadows have included turnips, hay, corn, and soybeans.

“Usually all of the buildings on an estate derive their architectural character from the main dwelling and repeat its motifs in simplified form.” (16) The striking stone cladding used in the main house and garage at Spruce Shadows Farm is in fact repeated in some of the buildings in the nearby farmyard. The house for the resident farm manager, though sheathed in wood shingles rather than stone, nevertheless echoes the Colonial Revival feeling of the main house with its simple Cape Cod styling and its similar relationship of house to garage.

As Spruce Shadows flourished through the years, so did the rural township it inhabited. The sweeping changes Bloomington underwent in the postwar decades have affected the farm’s acreage if not its buildings, and Spruce Shadows increasingly has felt the pressure of nearby development. In the 1960s, the Kelleys opted to sell some land to Control Data Corporation, which built a headquarters campus near the farm. Continued commercial and recreational development has kept the Kelleys’ acreage in demand, each year pushing the value of the farm higher. In 1980, the 1,000-acre farm carried an estimated value of more than $3 million. By 1986, after the Kelleys rejected offers directly from the developers of the Mall of America, the City of Bloomington condemned a 30-acre section of the farm to acquire it for the mall project. The Kelleys were compensated $10.4 million for the condemned parcel. (17)

More advertisements from Minnesota Guernsey News

The Kelleys’ land—both in Bloomington and at the cattle farm in Stillwater—continues to suffer threats from nearby development. Agricultural properties throughout the state face similar pressures. “Minnesota farmland is turning into homes and shopping centers at a rate of 24,000 acres a year,” the Saint Paul Pioneer Press reported in 1997. “Not surprisingly, most of the Minnesota farms biting the dust are in the seven county Twin Cities metro area. Census figures show that metro area farms declined 21 percent from 1982 to 1992, from 5,662 farms to 4,489 farms.” (18) Along with those farms are undoubtedly a few country estates established by the Twin Cities’ earliest suburbanites.

Cynthia de Miranda writes about the history of the built environment for Hess, Roise and Company, a Minneapolis based historical consulting firm with nationwide experience. She lives in Minneapolis.

The Architect: Magnus Jemne

Magnus Jemne in 1931. Minnesota Historical Society

One of the distinguishing characteristics of a gentleman farmer’s estate is the presence of an architect designed home rather than a more typical vernacular farmhouse. Spruce Shadow’s owner credits the buildings at the farm to Magnus Jemne, a Saint Paul architect who practiced throughout the first half of the 20th century.

The Davidson House at 344 Summit Avenue in Saint Paul 1998.

Jemne emigrated from Norway as a teenager around the turn of the century and attended high school in Ashland, Wisconsin. He then lived in Saint Paul for a short time, working as a draftsman in Cass Gilbert’s local architectural firm, which Gilbert established while he was in town designing and building the Minnesota State Capitol. Jemne later moved east to attend the University of Pennsylvania, where he received his architectural degree. At some point before 1916, he returned to Saint Paul and began practicing as an architect. From 1916 until 1925, he was in partnership with Thomas Holyoke, another of Gilbert’s former draftsmen.

While Jemne is best known for the highly praised 1931 Art Moderne clubhouse he designed for the Saint Paul Women’s City Club (later the Art Museum of Minnesota), his commissions generally consisted of houses for wealthy clients. Unlike the cutting-edge clubhouse, Jemne’s residential work has been described as traditional and undistinguished. He employed elements from a number of styles, including Colonial Revival, Tudor, and Arts and Crafts Bungalow. While the houses often display steeply pitched gabled or gambrel roofs with dormer windows, the architect used materials and overall massing to create variety among his designs. Jemne worked with stone, brick, wood, and stucco, sometimes combining stone with wood siding as at Spruce Shadows. Some houses are highly symmetrical (like the house at 15 Crocus Hill in Saint Paul), while others use cross gables or varied rooflines to achieve a more picturesque feeling (like Jemne’s own Saint Paul home at 212 Mount Curve Avenue). Designs dating from Jemne’s partnership with Holyoke were more elaborate, including the large Tudor manor at 344 Summit (the Davidson House); it is not known, however, to what extent Jemne was involved in the projects from that period that are generally credited to Holyoke.

Magnus Jemne designed this house at 212 Mount Curve in Saint Paul where he lived with his wife, 1998.

Supporting documentation of Jemne’s connection to the farm could not be found. Still, it seems likely that Jemne designed the stone-dad buildings at Spruce Shadows. The materials and stylistic details were certainly part of the architect’s repertoire, and the prominent Kelley family was the type of client Jemne attracted. Furthermore, in addition to the houses Jemne designed in the fashionable districts of Saint Paul, he also may have worked on the buildings at Green Acres, a summer farm in Cottage Grove built for Roger Shepard and generally credited to Holyoke. The farmstead, built in 1920, mimicked the “continuous architecture” style of New England farms, with rows of attached barns and outbuildings. Stylistic details such as wood-shingled gabled roofs, wood-shake siding, and a domed cupola lend a Colonial Revival appearance to the buildings. In addition, there are two detached outbuildings: a “stylish and well-built” poultry house and a gableroof barn.

Sources: Northwest Architectural Archives, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities; interview with the current property owner by Charlene Roise, June 30, 1994, Bloomington; Linda Mack, “Deco Downtown Stepping Stones: A Star Tribune Architectural Walking Tour,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, November 5, 1990; and Mike Clifford, Saint Paul Heritage Preservation Commission, “Minnesota Museum of Art/Saint Paul Women’s City Club Site Nomination Form,” July 27, 1978.

References

1. Judith Martin and David Lanegran, Where We Live: The Residential Districts of Minneapolis and Saint Paul (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1983), 3-4.

2. Penny A. Petersen, “Colonel William S. King and the Lyndale Farm,” Lake Area News, February 1991, 34-35; and Garneth 0. Peterson, “The James J. Hill North Oaks Stock Farm: James J. Hill and Agricultural Diversification in the Northwest,” 1996, prepared by Landscape Research for the Hill Farm Historical Society, 2, 15.

3. “Bloomington Historical Sites,” Hennepin County History, Spring 1970, 27; Scott Donaldson, The Making of a Suburb: An Intellectual History of Bloomington, Minnesota (Bloomington, Minn.: Bloomington Historical Society, 1964), 39; Charlene K. Roise, John Lauber, and Cynthia de Miranda, “Minnesota Public Radio Tower Project: Cultural Resource Evaluations of Dan Patch Race Track Site and Minnesota Masonic Home,” prepared by Hess, Roise and Company for System G, Saint Paul, April 1995; and “AM. Country Club Has One of the Most Beautiful Views in the Village,” Bloomington Sun, August 9, 1958.

4. Inventory form, “Green Acres,” State Historic Preservation Office files, Saint Paul.

5. “What This Magazine Stands For,” Country Life in America, November 1901, 24- 25.

6. Penny Petersen, 33-35; Albro Martin, James J Hill and the Opening of the Northwest (New York: Oxford University Press, 1976), 7-12.

7. Garneth Peterson, 3; Robert Hoffman, “The Country Gentleman Today,” Country Life, January 1932, 65.

8. Hoffman, 65.

9. Here and two paragraphs following: Information about structures at the farm was obtained from a brief site survey and interview with the current property owner, both conducted by Charlene K. Roise in 1994. Aerial photographs of Bloomington, available at the Borchert Map Library at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities, show the farm between 1937 and 1980.

10. Charlene K. Roise, Shawn P. Rounds, and Cynthia de Miranda, “Minneapolis-Saint Paul Airport Reconnaissance/IntensiveLevel Survey (for Long-Term Comprehensive Plan Alternative Environmental Document): The Built Environment (SHPO #94-0681),” prepared by Hess, Roise and Company for the Metropolitan Airports Commission and HNTB, Inc., Minneapolis, August 1995, 54.

11. “James E. Kelley, 93, a St. Paul Attorney and Businessman, Died Thursday at His Home in Bloomington, “Star Tribune, October 27,.1989.

12. “Kelley Died Thursday”; Polk’s St. Paul City Directory 1933 (Saint Paul: R. L. Polk and Company of Minnesota, 1933), 611 and 594.

13. Scattered issues of the Minnesota Guernsey News are available in the periodical stacks at the Central Library on the Saint Paul campus of the University of Minnesota Twin Cities. See “Spruce Shadows Cow Sets New State Record,” June 1945, and “T-C Parish Show Outstanding,” August 1948.

14. Advertisements for Spruce Shadows Farm appeared regularly in Minnesota Guernsey News and generally listed Kelley as owner along with the names of the current manager, herdsman, and consultant. Advertisements included other facts about the farm, such as the size of the herd, etc. For information on the Stillwater farm, see “Twin Cities’ Biggest Farm May Go From Raising Cows to Selling Lots,” Saint Paul Pioneer Press, May 12, 1997, lA.

15. “Kelley Died Thursday”; Paul Gustafson, “Savvy Farmer’s Patience May Reap Him Fortune,” Minneapolis Star, July 24, 1980; and Dave Beal, “Waiting for the Megamall Boom,” Saint Paul Pioneer Press, January 14, 1991, BS.

16. Stanley Taylor, “Developing the Country Estate,” Country Life, March 1929, 68-70.

17. Beal, BS; Gustafson, 3.

18. “Twin Cities’ Biggest Farm May Go,” lA.