by Susan Marks-Kerst

This article was originally published in Hennepin History Magazine, Spring 1999, Vol. 58, No. 2

General Mills touted Betty Crocker’s homemaking expertise in this Gold Medal Flour booklet in 1925. Photo credit: General Mills, courtesy of Jeremy Gale

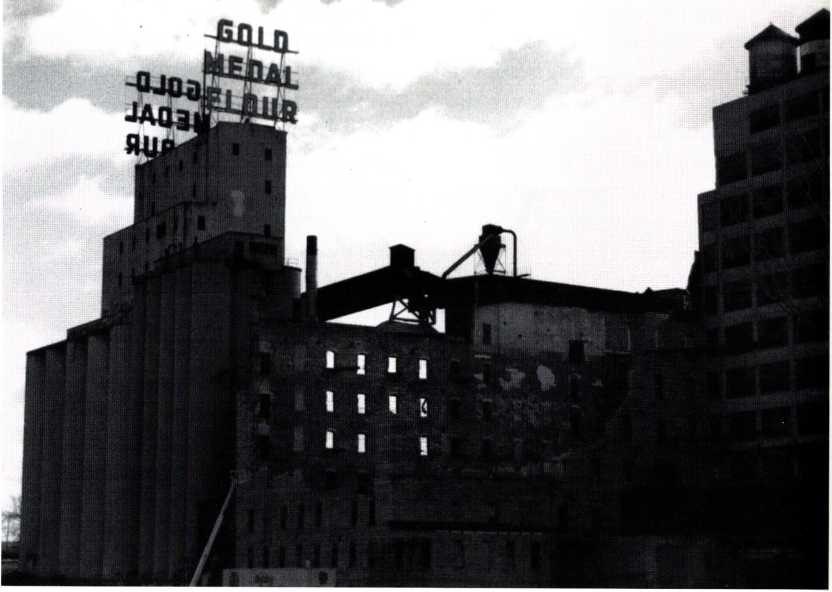

Among the ruins of the old mill district in downtown Minneapolis are the crumbling reminders of a once-booming flour industry that put Minnesota on the map. Lately, a resurgent energy has seized the former milling district. As Minneapolis searches for its roots, plans are underway for extensive renovations. Current plans include the development of Mill Ruins Park, with connecting trails and upscale private housing along the riverbank. Also, the Minnesota Historical Society plans an impressive 50,000 square-foot milling museum inside the fire-damaged Washburn “A” Mill, overlooking St. Anthony Falls. The mill once belonged to the Washburn Crosby Company, forerunner to General Mills Incorporated and the original home of Gold Medal Flour, WCCO, Wheaties, and national phenomenon Betty Crocker.

General Mills’ trademark homemaker, Betty Crocker, made her way into homes across the nation, becoming a permanent fixture in America’s collective kitchen. Despite her humble beginnings on the shores of the Mississippi River, Betty rose to national fame. The fictitious Betty Crocker and her supporting staff influenced the way America shopped, cooked, ate, and served meals. Through her cooking schools, radio shows, print advertisements, cookbooks, television programs, and commercials, she nurtured and shaped the American homemaker. Betty Crocker spoke to women in a tone that was encouraging and inspirational. Her message always remained the same to each and every homemaker: “Yes, you can do it, and I can help you.” Betty and her staff were innovative, clever, practical, and reassuring. Her longevity is testimony and tribute to her impact on society.

Behind the success of Betty is one of the most remarkable and innovative advertising campaigns in American history. In the modern era of the 1920s, characterized by uncertainty, Betty played the role of surrogate mother and grandmother to generations of homemakers. Most advertisers skillfully manipulated female customers by persuading them to buy things they did not need. In the early 20th century, advertisers played upon social taboos, insecurities, and reinforced stereotypical gender roles to sell products. While Betty’s ad-makers undoubtedly also contributed to the stereotypical image of woman as homemaker, they also transcended common advertising practices by using Betty as a service that was valued by homemakers. The strategic advertising of Betty Crocker set her campaign apart from other ad campaigns and catapulted her to icon status.

Women and the modern era

When Betty Crocker was introduced in 1921, America was embarking on a dramatic new era of consumerism. World War I was over and new technological developments dominated national advertisements. Magazines that had been published in black-and-white, such as The Saturday Evening Post and Ladies ’ Home Journal, were printed now in vibrant color. Visually stunning ads sprang from the pages of magazines, proclaiming that the new modern age had arrived! Luxury items such as automobiles, golf clubs, radios, kitchen appliances, color- coordinated bath towels and an array of personal toiletries became immensely popular and affordable to middle-class consumers. This wave of new technology swept through urban America and with it a renewal of materialism reminiscent of the Industrial Revolution.

The early 1920s also marked a new era for advertising. For the first time in American history, advertising was considered a major industry. Advertising could not have flourished without the female population, in particular that of the middle class. Women were the primary purchasing agents for their families. Advertising journals attributed 80 to 85 percent of all consumer spending to women.1 Accordingly, advertisers focused on women, paying close attention to their spending habits. Copywriters prided themselves on knowing the vast female market and pitched almost all ads towards them. The challenge for ad-makers, however, was how to capitalize on the ambiguous new American woman.

The predictability of the Victorian era had been shattered by the dislocating effects of rapid urbanization, industrialization, and ultimately a world war. Gender roles changed quickly for many young women. They were leaving their families in rural areas and moving to large urban centers to find work or attend college.

As America moved from an agrarian society to an urban society, employment and education opportunities became more varied for women. Caucasian, non-immigrant women often found the best paying jobs because of their educational background and because of office employers’ preferences and politics. Recent immigrants and minority women had fewer educational opportunities and found less-desirable positions in restaurants, shops, factories, and domestic service. While opportunity was disparate, more women enrolled in colleges and held paying jobs than they had previously. Public spheres once considered men’s territory now were occupied by both women and men.

Despite the changing roles of women and the perceived break from traditional roles, the common objective of marriage and children prevailed for the majority of women. Society expected that middle-class women would quit their jobs or schooling once they married. This practice left women in a vulnerable and insecure position at home and in society. Years spent in college and long work hours left many women unprepared for the cult of domesticity. Women were expected to become full-time homemakers in modern new homes without the training required to run a successful household.

Traditionally, women learned homemaking from their mothers, who, in turn, had learned from theirs. Extended families often lived in the same households or communities where women could rely on one another for solving homemaking quandaries. In the 20th century, however, most new brides lived away from their families and could no longer count on support and guidance on domestic matters. Even if a mother lived near her daughter, she could not counsel her on home appliances that she did not own herself.

The remains of the Washburn Crosbry “A”Mill in 1999. The original home of the Betty Crocker Home Service department was within this milling complex.

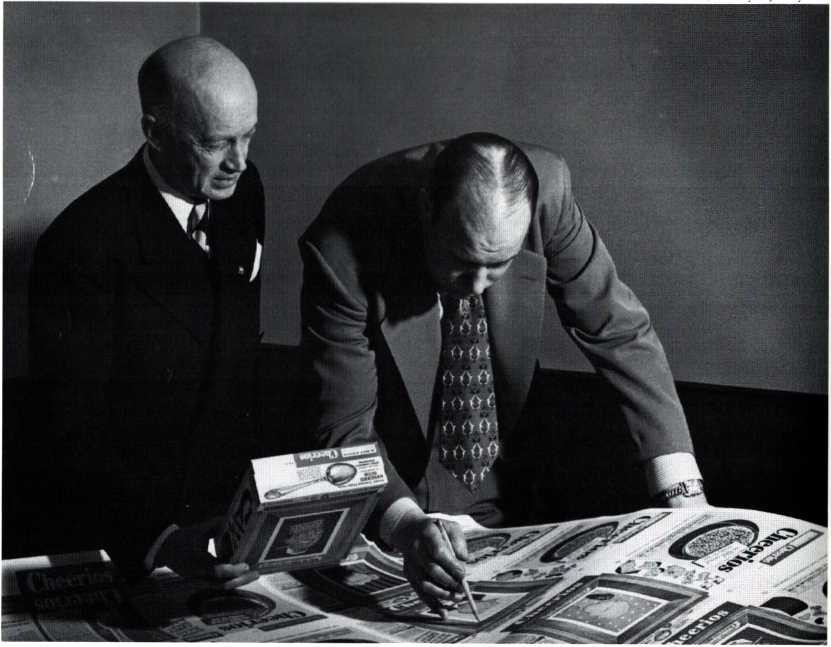

Sam Gale (left) working on a 1950s ad campaign with another executive of General Mills. Gale was by then a vice president.

All-electric kitchens were replacing iceboxes and wood-burning stoves. Running water was not a luxury but a necessity in urban America. And washers and dryers were the latest must-have gadgets for urbanites. Left to her own devices, the homemaker tended to feel inexperienced and undereducated in modern ways. Companies such as Washburn Crosby jumped at the opportunity to “educate” women on the proper way to run a modern household. According to advertising historian Jackson Lears: Domestic scientists and processed-food advertisers, addressing middle-class women who were increasingly isolated from kin and communal food ways, sought to reassure their audience by providing them with a sense of control, a new set of rules.2

Companies repeatedly designed fictitious “friends” to help the consumer with questions while plugging their own products. The success of these advertising campaigns was measured by consumer response, personal letters, coupon returns, and, of course, increased sales. Betty Crocker was among the first of these “friends” to appear and gain national recognition. She was also the only “friend” to last 78 years. Betty was not, however, an overnight success.

Betty in 1936

Photo credit: General Mills

The Washburn Crosby Company

The Betty Crocker legacy is due in part to the highly insightful in-house advertising team and home service staff that worked for the Washburn Crosby Company, the forerunner of General Mills. In the early 1920s the Washburn Crosby Company was one of the giants in the milling industry. The Washburn Crosby Company, like most flour milling companies, concentrated its advertising efforts on trade journals geared towards commercial bakers, but it also realized the untapped purchasing potential of women consumers. Historically, women were responsible for meal preparation, and new opportunities for women did little to change this tradition. The company knew that homemakers had questions about new products, new technology, and new recipes.

From the first printing of The Gold Medal Cookbook in 1903, the company could not keep up with the thousands of requests for copies. Meanwhile, the Washburn Crosby Company decided on a unique approach to connecting with their customers. It developed a strategy to directly influence potential buyers by organizing cooking demonstrations at churches and schools in Minnesota and Wisconsin. Women were invited to participate by asking baking and cooking questions of a knowledgeable Gold Medal staff. Not surprisingly, the response from customers was overwhelmingly enthusiastic. The Washburn Crosby Company attempted to fill the role of mother and grandmother expertise left empty by new technology and advancements. Demonstration attendance swelled, and requests for the company cookbook continued to skyrocket. Clearly, the Washburn Crosby Company had arrived at a new way of marketing its products, combining the age-old method of selling directly to the customer with educational components that empowered its customers. The invention of Betty Crocker embodied and personified this successful education-style relationship with consumers.

Betty is born, 1921

Behind the creative genius of Betty Crocker were many talented individuals employed by Washburn Crosby. One in particular, Samuel Gale, is credited as the driving force behind Betty. Gale was connected with homemakers because of the early direct contact he had with them at cooking demonstrations. He knew their questions and concerns about cooking and baking, and he empathized with their confusion. He understood from the hundreds of letters the company received each week that the modern age of homemaking had left many ill-prepared for their responsibilities. He took it upon himself and his small staff to reply to each letter personally, but he never felt right about signing his own name.3 As letters increase each week, his task became increasingly difficult. One occurrence in particular launched an unprecedented turn of events.

One Gold Medal flour ad featured a jigsaw puzzle on the back of a national magazine. The solved puzzle depicted a scenic village with happy little villagers carrying sacks of Gold Medal Flour. The prize for completing the puzzle was a pincushion resembling a miniature sack of Gold Medal Flour. Washburn Crosby was wholly unprepared for the onslaught of 30,000 responses to the puzzle that poured in. The company also was shocked and panicked by the hundreds of personal letters asking baking questions. It considered the avalanche of mail an emergency, and Gale was appointed to handle the crisis. The directors accepted a suggestion that they invent a friendly woman to act as a figurehead for the Home Service staff. Her name, rather than his, could be used on correspondence.

Betty Crocker’s surname was chosen in honor of William Crocker, a recently retired and well-loved director of the Washburn Crosby Company. Betty was chosen because it sounded light, cheery, wholesome, and folksy.4 For three years she was Betty “in name only” for correspondence and company literature. Betty Crocker represented the Gold Medal Home Service Staff, which became the General Mills Home Service Department when the Washburn Crosby Company consolidated in 1928. According to General Mills historian James Gray: The function of General Mills’ Home Service Department has been to convince the buyer that she was being introduced, through literature, to “tangible ways of using the product more effectively in carrying out her basic job.” The modern housewife was susceptible to such suggestions for two reasons:

- The advanced education many of her kind had received made them all sympathetic to the new approach (planning a meal with reference to proper dietary balance; measuring in calories).

- As a busy college student she had not had time to serve the apprenticeship of the stove that had given her mother and grandmother training.5

The acceptance of Betty Crocker as valuable to the homemaker was slow. Establishing Betty as the authority in domestic realms was not an easy task. Advertising is inherently competitive, and customer loyalty is not won overnight. Betty’s ad-makers had to persuade homemakers that she was truly on their side and not deceiving them like many other advertisements.

Advertising in the modern era

It has been said that advertisements reflect society at large. Advertisements of the 1920s, however, were decidedly less a reflection of society and more a reflection of a consumer culture. Most companies simply wanted to “move merchandise” and would use any means to do so. Industry leaders were well aware of the insecurities of many women in modern society and tried to manipulate them to create new markets. Advertisers tended to view women as consumers who made emotional purchases based on fear and inferiority complexes.6

For example, a 1925 Listerine magazine advertisement shows a young, beautiful woman looking crestfallen and alone at home. The eye-catching headline reads, “Often a bridesmaid but never a bride.” The text goes on: Edna’s case was really a pathetic one. Like every woman, her primary ambition was to marry. Most of the girls in her set were married—or about to be. Yet not one possessed more grace or charm or loveliness than she. And as her birthdays crept gradually toward that tragic thirty-mark, marriage seemed farther from her life than ever. She was often a bridesmaid but never a bride. Why was her life so miserable? She had breath so bad that no one would marry her or suggest that she use mouthwash. Listerine’s ad campaigns revolved around “fear advertising” and “whisper copy” and fostered enough anxieties to change people’s behavior. According to advertising historian Juliann Sivulka, “The (Listerine) campaign proved so successful that people’s behavior changed. The morning mouthwash became as popular as the morning shower.”

That the majority of consumers believed mouth odor would prevent marriage and potential happiness is doubtful. Nevertheless, this advertising style tapped into a genuine fear held by the public. No one wanted to be judged on on a basis of offensive personal odor. Instead of responding to consumer demand, advertisers in the 1920s were trying to create it. Moreover, these advertisements repeatedly reinforced the misconception that women were living in a society that revolved around clean homes and fresh appearances, with dire consequences for nonconformity from an unforgiving society. Within their own field, advertisers proudly admitted that they did not reflect an accurate and respectful view of society. Many were not concerned with truth as long as merchandise sold. Some ad-makers justified their lies by claiming it was for the betterment of society. John Benson, president of the American Association of Advertising Agencies, confessed in 1927: To tell the naked truth might make no appeal. It may be necessary to fool people for their own good. Doctors and even preachers know that and practice it. Average intelligence is surprisingly low. It is so much more effectively guided by its subconscious impulses and instinct than by reason.8

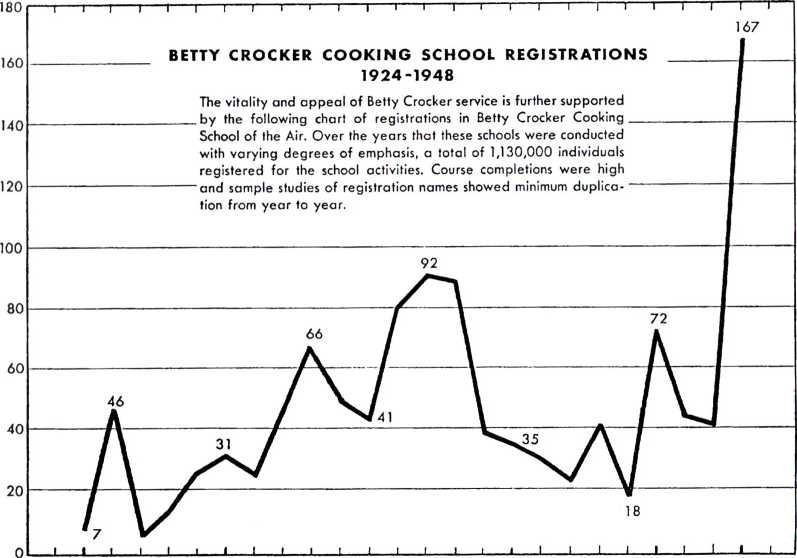

Both women and men came under fire from the advertising community. Manipulating the public and selling products was not enough; some added insult to injury. According to a successful advertising agency, Ruthrauff and Ryan: The great bulk of people are stupid. After all, men and women in the mass apt to have incredible [sic\ shallow brain-pans. In infancy they are attracted to bright colors, glitter and noise. And in adulthood they retain a surprising similar set of reactions.9 Undoubtedly the Ruthrauff and Ryan staff considered itself anything but the “great bulk of people.” In the often hostile and degrading advertising climate of the 1920s, Betty Crocker was a refreshing change with her down-to-earth homemaking appeal. Betty was solicitous, and she softened the male-corporate image. As her popularity grew from print ads and personal letters, the public demanded more advice from Betty. In an effort to reach and service more homemakers, the Washburn Crosby Company established Minneapolis-based Betty Crocker Cooking Schools throughout the Midwest. The school was immensely popular with local women. Soon the company found itself unable to accommodate the large number of registrants. A new medium solved the dilemma.

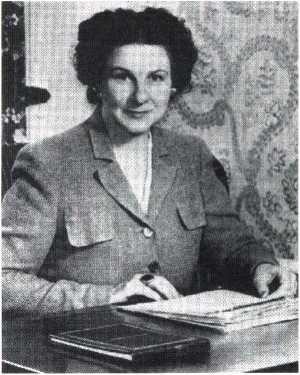

Marjorie Husted scripted and was the voice of Betty Crocker in Minneapolis.

Kilter radio

Radio was a novelty in the 1920s, but it was gaining popularity and acceptance, especially among the middle classes. In 1926 radio reached 20 percent of all American families. Two years later, radio reached 30 percent and continued to rise.10 Radio waves were the wave of the future, and advertisers knew it. Most found it tantalizing yet perplexing to penetrate the intimacy of the family circle in the privacy of their own homes.11 Initially, only the elite owned radios, and advertisers were reticent to resort to crass emotional appeals, but as the medium grew popularity and affordability, advertisers targeted its growing market. Radio advertisers generally moved from responsible advertising towards a fantasy-sell. According to advertising historian Roland Marchand: “People seemed to want escapist fantasy, a feeling of personal identification with fictitious characters, celebrities, even more than they wanted products.”12 Radio advertising had to be much more entertaining and engaging than print advertising. If the listener was not satisfied, intrigued or entertained, the radio could be switched off.

The Washburn Crosby Company boldly entered the world of radio by purchasing a failing St. Paul radio station. It changed the call letters from WTAG to WCCO to reflect the company’s initials. By 1924, Betty hit the airwaves with “The Betty Crocker School of the Air.” A female voice announced that Betty would be dropping in each week for a visit and a chat about cooking and homemaking.13 The show was a smashing success from the start. Women within broadcast distance of WCCO were tuning in, cooking, and sending Betty hundreds of lerters each week. Within one year the show expanded to 13 regional stations. The show was so popular that the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) added the cooking show to its 1927 national lineup. Betty’s on-air cooking show was not only the first ever of its kind, but it was also the longest running. In the show’s 27-year history more than a million listeners graduated from the on-air cooking show.14

In the first year of the show, several Washburn Crosby employees supplied the voice of the on-air Minnesota Betty. Among the first were Marjorie Husted, director of the Betty Crocker staff, and Blanche Ingersoll, who later was sent to Buffalo to train the actress playing Betty for the New York show. Betty’s tone was sensible, friendly, chatty, and offhanded.15 Women felt comfortable with her style, and they could relate to her easily. Ingersoll encouraged her trainee to adopt the same on-air personality for consistency and maximum effect. The outcome was an unprecedented success, and the Buffalo show proved even more popular than the one in Minneapolis. Letters poured in by the tens of thousands.16 Although different women played the on-air voice of Betty in different regions, the overwhelming response was the same. Homemakers found her show helpful and useful in their everyday lives.

Betty and America’s troubled times

In 1928, the Washburn Crosby Company consolidated with other mills to form General Mills Incorporated, which soon became the largest milling company in the world. At the same time, the company was riding high off the surprise national success of Betty Crocker. During this period of great economic growth for General Mills, about 4,000 letters addressed to Betty Crocker arrived daily.17 General Mills fully embraced the selling power of Betty Crocker and began a pattern of using her influence with homemakers in a variety of new ways.

Betty Crocker has been without question a genius of adaptability. As the nation sunk deeper into the Great Depression in the 1930s, she expanded her service to the nation. Undoubtedly, the men and women behind Betty Crocker were moved by the thousands of letters that poured into General Mills with pleas for Betty’s help.18 Homemakers worried about budgeting and preparing meals without sacrificing the nutritional needs of their families. The Home Service Department answered the call with a free booklet from Betty that addressed budgeting food on depression-era wages, balancing nutrition, and maximizing relief foods. The booklet was a saving grace for many Americans, and its sound advice won national recognition among nutritionists and social workers.19 Incidentally, General Mills was one of the “golden eight” corporations that never failed to earn and pay a regular dividend on common stock without reduction during the Great Depression.20 Betty appeared as a friend to her public in need. She must have been a refreshing change from the increasingly hard-sell advertising techniques of the Great Depression and World War II. Advertisers preyed on the nation’s collective rising fears and insecurities.

Betty Crocker helped homemakers through the rationing during World War II with the recipes and hints in this booklet.

On this page of the booklet shown , Betty told how to stretch the milk supply

For example, Union Central Life Insurance Company, like other such firms, ran guilt-evoking ads that pictured sad-faced boys who did not stand a chance of making it in the world because their fathers did not buy them life insurance. The message was clear that parents could “rescue the American dream” only by spending their hard-earned money in the throes of the Great Depression.21

Because of her care-taking role, Betty’s popularity soared in the early 1940s. (General Mills executives decided to confirm what they already knew about Betty and her influence. A company-sponsored survey showed that Betty Crocker was known to nine of ten American homemakers.22 A couple of years later, in April 1945, Fortune magazine claimed Betty was the second best-known woman in America, second only to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.23 From that publication on, Betty Crocker was touted as the “First Lady of Food.” Betty’s continued influence on the nation was not lost on the U.S. government.

In 1945, the Office of War Information enlisted the help of Betty and her staff. At its request, the Home Service Department produced a series of Betty Crocker war broadcasts. The program, entitled “Your Nation’s Rations,” aired on NBC radio for four months. The programs were geared toward helping homemakers make the most of rationed food on a budget. The Home Service Department spoke through Betty, making it clear that the nutrition of American families should not be compromised even in turbulent times. Almost seven million free copies of a Betty Crocker wartime booklet, Your Share, were distributed across the nation. True to the Betty Crocker “friend” style, the booklet offered advice on cooking, shopping, shortcuts, and time-and-money- saving techniques. Five additional Betty Crocker wartime publications followed. One in particular—Thru Highway of Good Nutrition—won national recognition from the American Red Cross for outstanding service in the nation’s best interest.

Queen of the Kitchen

Betty’s influence and popularity did not go unnoticed by companies and their advertisers. A host of Betty-type domes- tic authority spokeswomen burst on the scene. Advertisers cashed in on copycat campaigns across the nation. According to historian Karal Ann Marling: Betty’s success spawned a whole sisterhood of look-alike household experts: Mary Lee Taylor of Pet Milk; Aunt Jenny, the “Spry” shortening lady; Jane Ashley (Karo syrup and Lint starch); Mary Lynn Woods (Fleisch- mann’s yeast); Kay Kellogg (Kellogg’s cereals); Martha Logan (Swift meats); Anne Marshal (Campbell soups) and Ann Pillsbury from Minneapolis-based Pillsbury Flour, General Mill’s chief competitor and rival.24

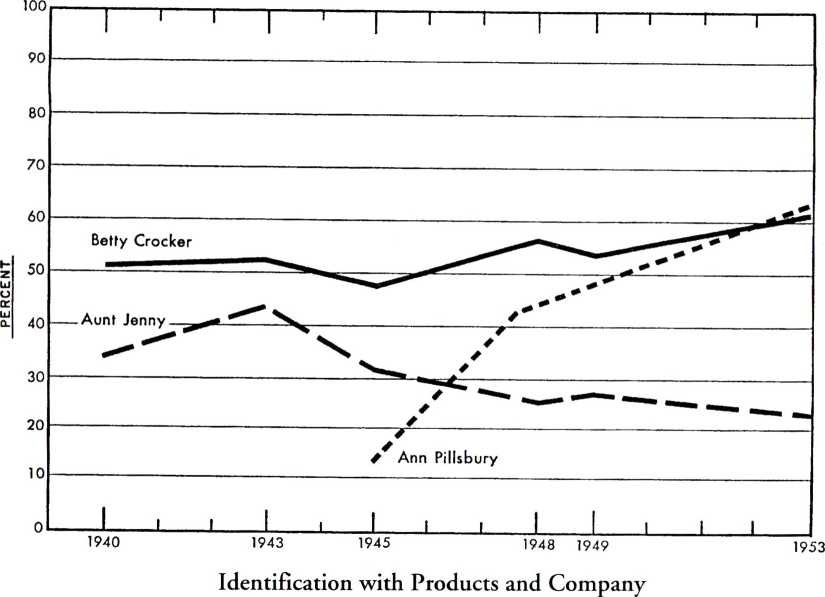

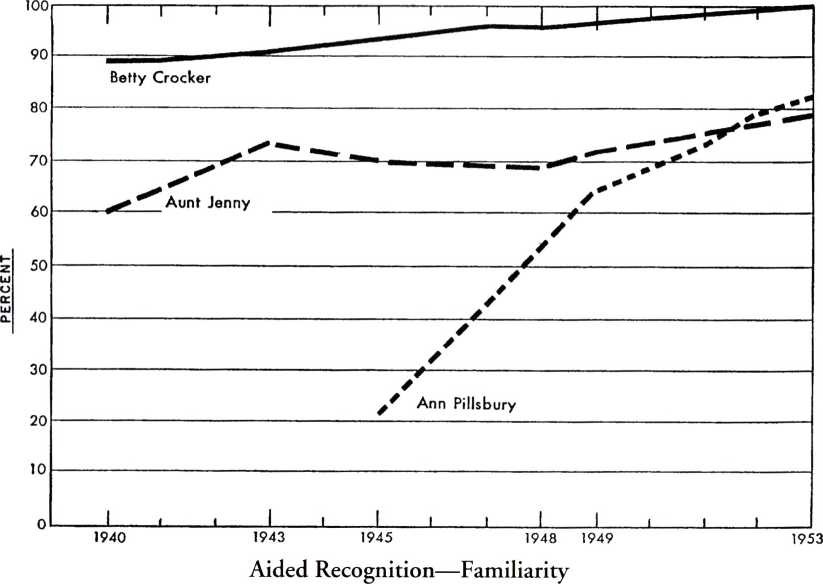

Of all the fictitious spokeswomen, Ann Pillsbury and Aunt Jenny worried General Mills the most. In a 1954 General Mills interoffice packet, The Betty Crocker History, the directors shared survey information among executives. Their biggest concern was that other fictitious spokeswomen would gain momentum and edge out Betty as the queen of the kitchen. According to the survey results, the market research team discovered that between 1940 and 1953 the name Betty Crocker was recognized more than 90 percent of the time compared to Aunt Jenny, who averaged 60 to 70 percent. Ann Pillsbury was not introduced until 1945, and her name recognition rose steadily throughout the year, surpassing Aunt Jenny but not Betty in recognition. The most troubling survey results for General Mills came from the survey about name association with company. Between 1940 and 1953 Betty was correctly identified with General Mills, the leader, until Ann Pillsbury passed her in 1953. Of the three, Aunt Jenny remained least successful in identifying with product and company. 25

In the end, General Mills had nothing to worry about. Today Ann Pillsbury and Aunt Jenny do not invoke even vague recognition in American reminiscences. Other spokeswomen may have been helpful to homemakers, but overall loyalties remained with Betty Crocker. Perhaps it is because her approach to selling and education was nonthreatening and truly helpful. Homemakers felt she could be trusted like a mother or grandmother, even if she was not real. Betty had been around longer than most domestic spokeswomen and had established herself as the authority in the kitchen. Nevertheless, Betty Crocker was in the arena of big business.

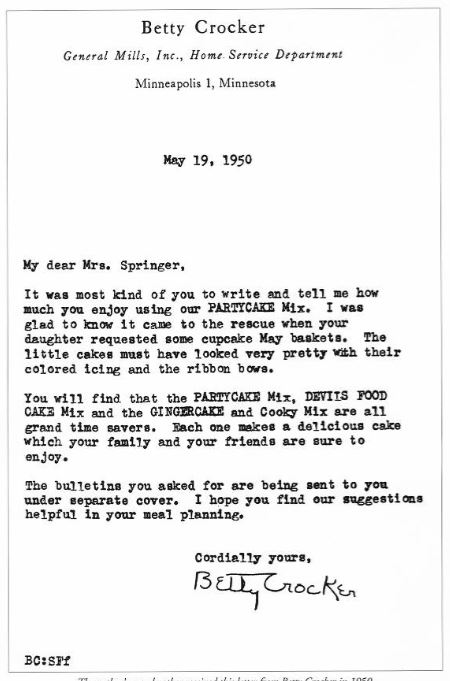

The author’s grandmother received this letter from Betty Crocker in 1950.

There is no doubt that the bottom line for General Mills and all other for-profit companies is to make money. Advertisers and food companies have always known the enormous purchasing power of women and the potential to create a larger market. In contrast with other companies, however, the advertisements that used the image or name of Betty Crocker showed integrity and refinement in an unscrupulous advertising era. In fact, General Mills’ in- house advertising department established three principles to guide its advertising efforts:

- Our advertising shall be truthful, informative and educational.

- Our advertising shall render the maximum of helpful service.

- Our advertising shall, insofar as possible, seek to expand markets rather than merely to take business away from competitors.26

Whether or not one believes General Mills has lived up to these ideals, it is certain that Betty pitched her products in a tone that was helpful to homemakers rather than scaring them into purchases based on fear and insecurities. Clearly, General Mills capitalized on Betty Crocker but not at the expense of the customer. Every company chooses its advertising path based on the potential for the best short-or long-term results. Some businesses judge advertising results based solely on bottom-line sales and enjoyed good short-term profits. Businesses such as General Mills, however, placed a high value on customer satisfaction along with high sales. General Mills was willing to make economic sacrifices to perpetuate the good reputation of Betty Crocker by implementing programs such as free nutritional booklets during the depression and World War II. In the decades following the war, General Mills offered community and school educational programs and hundreds of college scholarships. For General Mills, any product with the trademark name Betty Crocker was synonymous with good customer relations. General Mills’ goal was to reap the rewards of long-term profits that are fueled by repeated customer satisfaction.

Conclusion

Betty was born into a new modern era and an often-hostile advertising atmosphere in the 1920s. She was one of the first fictitious spokeswomen to take homemakers seriously and treat them with respect. The men and women who made up the collective spirit of Betty Crocker were real heroes to a nation that needed assistance and advice during difficult times. Whether it was a new bride without proper training in a modern kitchen or a family that was in danger of malnutrition during the Great Depression, Betty Crocker was instrumental in helping homemakers to cope and families to thrive. During World War II, Betty reassured the nation’s homemakers on the airwaves that they were not alone, and that if everyone did her part, working together they could help win the war. Perhaps Betty’s script was just telling people what they wanted to hear. Or, perhaps during the panic and uncertainty of wartime, reassuring words from a mother figure were not only wanted but needed.

Today, Betty’s success is measured predominantly by the sales of her grocery products and cookbooks. But it is also measured by the personal letters, phone calls, and e-mails that pour in and are personally answered each day. All the years that the Washburn Crosby Company and General Mills devoted to community service have paid off in customer loyalty. Other fictitious spokeswomen failed to survive in an environment where Betty reigned supreme. Her legacy has lived on as the roles of woman have changed. Her role changed too, evolving over seven decades. Throughout the years, she has shown that respect and decency pave the path towards longevity. Millions of women have written her letters, listened to her programs, enrolled in her cooking school and purchased her products and cookbooks. In doing so, women have sent the message that Betty has given them exactly what they needed— advice, education, empowerment. The First Lady of Food continues to serve her public, playing surrogate mother to new generations, proving that American homemakers still need Betty Crocker.

Betty in 1955

Betty in 1965

Betty in 1968

Betty in 1972

Betty in 1980

Betty in 1986

Betty in 1996

References

- Roland Marchand, Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity 1920-1940 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), 66.

- Jackson Lears, Fables of Abundance: A Cultural History of Advertising in America (New York: Basic Books, 1994), 184.

- James Gray, Business without Boundary: The Story of General Mills (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1954), 173.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 178.

- Marchand, Advertising the American Dream, 19.

- Juliann Sivulka, Soap, Sex, and Cigarettes: A Cultural History of American Advertising (Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing, 1998), 160.

- Marchand, Advertising the American Dream, 85.

- Ibid., 67.

- Ibid., 87.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 115.

- The Story of Betty Crocker, General Mills Promotional Document, 1998.

- Ibid.

- Gray, Business without Boundary, 177.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 178.

- The Story of Betty Crocker.

- Ibid.

- James Gray, “General Mills—An Idea In Action,” General Mills Horizons (for stockholders), Spring 1953 (25th Anniversary Issue): 6.

- Marchand, Advertising the American Dream, 131-32.

- Gray, Business without Boundary, 173.

- Ibid.

- Karal Ann Marling, As Seen on TV: The Visual Culture of Everyday Life in the 1950s (Cambridge: Harvard Press, 1994), 206.

- The History of Betty Crocker, General Mills Internal Document, 1954.

- General Mills Annual Report, 1963

The author thanks Suzanne Chinnock, Jeremy Gale, J. D. Crandall, and David Stevens for their time, effort, and advice. Thanks also to staff members at General Mills, the Minnesota Historical Society, and Hennepin History Museum for helping with research for this article.

NOTE: Betty Crocker is a registered trademark of General Mills, used here with permission.

Susan Marks-Kerst is a graduate student in history and American studies at the University of Minnesota. If you have personal stories about Betty Crocker and are willing to share them, please write Susan in care of the Hennepin History Museum.