Sarah Harrison Knight: Broader and Grander Work

by Mary Hawker Bakeman

This article was originally published in Hennepin History, Fall 1993, Vol. 52, No. 4

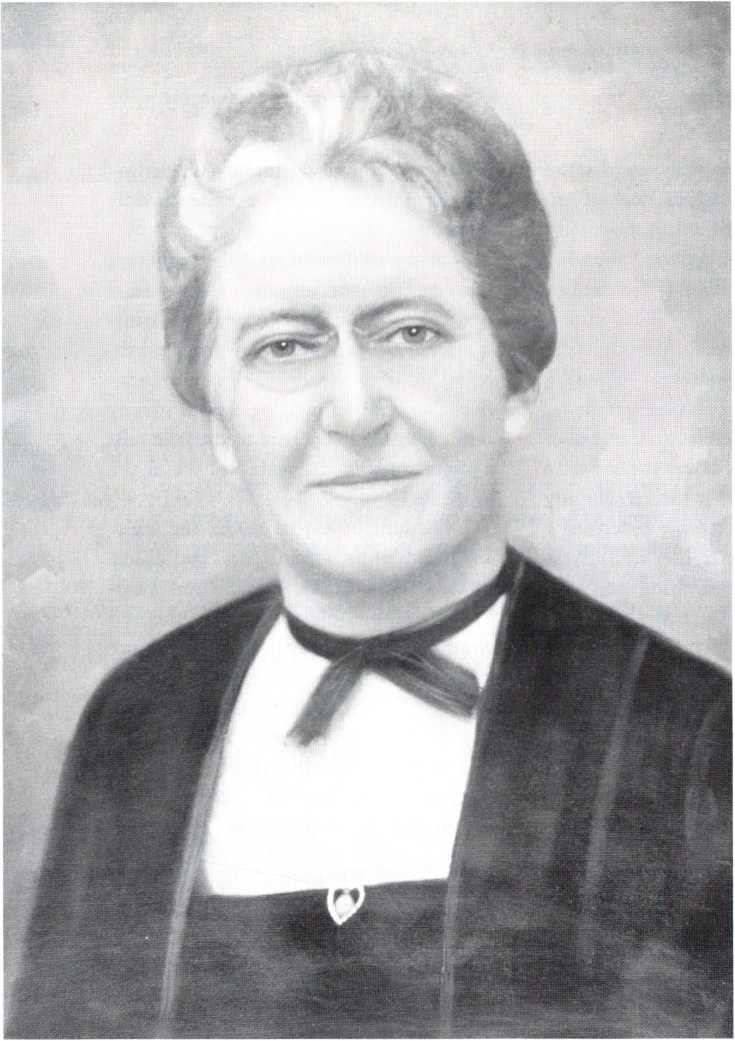

Sarah Harrison Knight

Courtesy of Methodist Hospital

A century ago, the Methodists of Minneapolis gave their city a new hospital dedicated to providing health care to the burgeoning population—especially the urban poor. Asbury Hospital, one of several hospitals growing out of organized religion’s recognition of health care issues, became reality under the strong guidance of Sarah Harrison Knight. It still exists today—though with a new name (Methodist Hospital) and in a new location (St. Louis Park, a Minneapolis suburb) within Hennepin County.1

A young widow and the daughter of strong pioneering Methodists, Sarah Harrison Knight did what her family had done: she educated herself, she observed and learned from others around her, she conceived a practical plan of action, and she recruited others to help convert her dream to reality. She was a leader when women were not encouraged to be leaders, and she devoted her own talents, money, energy and self to improving conditions for others less fortunate than she.

Her family was wealthy as well as prominent in business circles and in the work of the Methodist Episcopal Church. She could have purchased any luxury she wanted, and she could have avoided the social problems around her. But like her family, she believed that the church, through its members, bore a great social responsibility.

Her comments made in 1895 still apply: “Now, the question is, are we accomplishing our work? It is evident that in a large measure we are, but in the opinion of many we have come to a time when we, as a Church, must decide whether we are to content ourselves to remain as we are, or to take up a still broader and grander work. A great field and a responsible future lies before us. Are we willing to go forward and occupy this field and assume these responsibilities?

“This does not mean that every one should found a college, build a church, give large sums of money, or any money; but every one, be he a member a month old, or twenty years old, in church life, should do something. Most of us have thought if we could not do some great thing, we could do nothing, but God does not look at it that way.”2 Sarah challenged herself, other members of her family, and her friends to take up “broader and grander work.” She knew no other way.

Sarah Harrison was born in Belleville, St. Clair County, Illinois, on October 30, 1849. She was the fourth child of Thomas Asbury Harrison and his wife, Rebecca Green Harrison. Sarah learned about personal and social responsibility early in her life. Her paternal grandparents, Reverend Thomas and Margaret Galbraith Harrison, had moved to Illinois from North Carolina in 1805, shortly after their marriage, because of their hatred for slavery. Among the early settlers in St. Clair County, they had to clear the land to farm it. Thomas’s name appears in the minutes of the First Quarterly Conference of the Belleville Church in 1836 as a “Local Elder,” and he preached twice a week in that area for many years. (In the 1850s, the Harrisonville Mission was part of the Lebanon District of the Southern Illinois Conference.)3

Thomas and Margaret Harrison had nine children, whom they raised to be devout Methodists and taught to care for others.4 Methodist camp meetings and revivals were frequently held in the area, and the Harrison family was likely well acquainted with the Methodist clergy. One son was given “McKendree” as a middle name, and another “Asbury,” doubtless in honor of Bishop William McKendree, the first U.S.-born Methodist bishop, and Francis Asbury, a contemporary of John Wesley who set up the itinerant ministry in the United States. One daughter, Anna, married Dr. Sylvanus M. C. Goheen, a medical missionary to Africa and a prominent contributor to the Methodist Episcopal (M.E.) Church, on December 10, 1843, in St. Clair County.5

Integrity in business ranked high with the Harrison family as well. In addition to his farming and preaching, Reverend Harrison established and operated a flour-milling business in Belleville, installing the first steam engine in Illinois. As the business grew, he included his family in its operation. The steady growth of the business required the construction of a new mill in 1836; it was lost to fire in 1843 and rebuilt in 1844. Regardless of the mill, the business was built on making a quality product, and the flour was well respected by the community. Sarah learned through her contact with the family business that success came with a Christian life and hard work and not from taking advantage of others.

In 1859, Reverend Harrison, with two of his sons and his three widowed daughters (William M., Hugh G., Anna, Olive, and Elizabeth) and their families, took a steamboat from Illinois to Minnesota via the Mississippi River. The next year, another son, Thomas Asbury Harrison (called Asbury, he was Sarah’s father), sold his mill interest in Belleville and traveled to Minneapolis with his family.6 Sarah was 11 years old at the time. The State of Minnesota was just two years old.

The members of Sarah’s family were not prepared for Minnesota winters, and they grew homesick for southern Illinois. Sarah remembered the first winter at their home at Fourth Avenue South and Seventh Street well: “Day after day it was 10, 20 and sometimes 40 degrees below zero, with the wind blowing a gale all the time, and our house built according to Southern ideas of architecture. The cold would be inconceivable to anyone who had not experienced such weather. Many a time I woke up in the morning with the bed covering frozen stiff from our breath.”

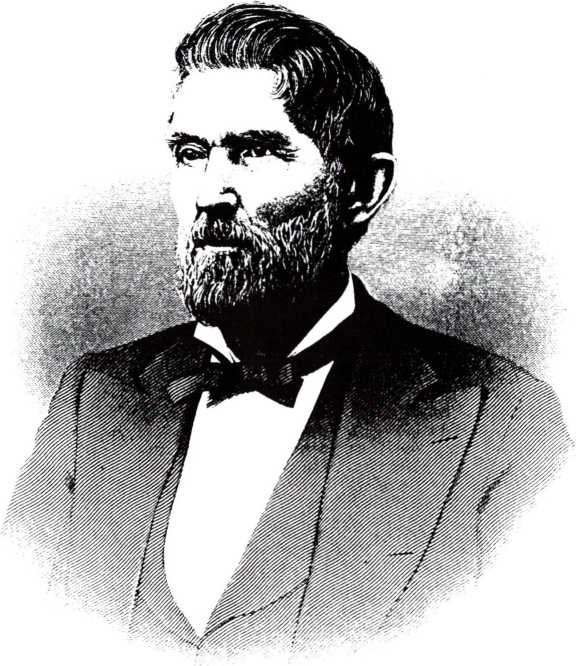

Although the occupation of each is listed as “Gentleman” on the 1860 U.S. Census for Minneapolis, Asbury and his brother Hugh were bankers.8 Financially conservative, Sarah’s father carefully considered all his business decisions, then worked hard to achieve his objectives. But moral principles and caring for other people were important to him. He was a strong supporter of Hamline University, a Methodist school in St. Paul, and he endowed professorships in the names of his wife and his eldest daughter, Caroline. He served on the Minneapolis School Board. And when he couldn’t serve as a soldier, he responded to President Abraham Lincoln’s request that businessmen help pay for the Civil War, without asking for notes in return. Isaac Atwater described him as possessing “unflinching integrity in all relations of life, a sound judgment and an indomitable will. Added to these was kindness of heart and a cheerful spirit . . . with the repose of strength … In his family he was ever loving and patient.”9 Sarah shared those characteristics.

Thomas Asbury Harrison was Sarah’s father, named for Francis Asbury, who set up the itinerant Methodist ministry in the United States. (Engraving from Isaac Atwater, History of the City of Minneapolis, 1893, in collection of Minnesota Historical Society)

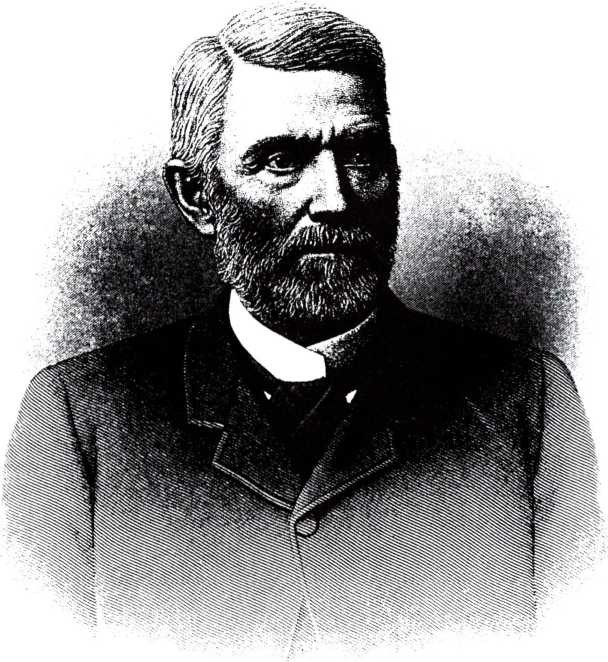

Hugh G. Harrison, Sarah’s uncle, worked, as did her father, as a banker in Minneapolis. Hugh later became mayor of the city. (Engraving from Isaac Atwater, History of the City of Minneapolis, 1893, in collection of Minnesota Historical Society)

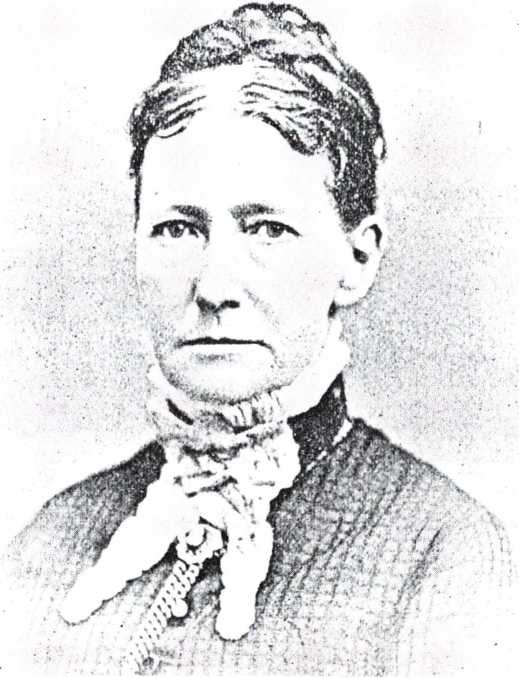

Sarah’s mother, Rebecca Green Harrison, for whom she later named the Rebecca M. Harrison Deaconess Home (Illustration from John Wesley Hill, Twin City Methodism, 1895, collection of the Minnesota Historical Society)

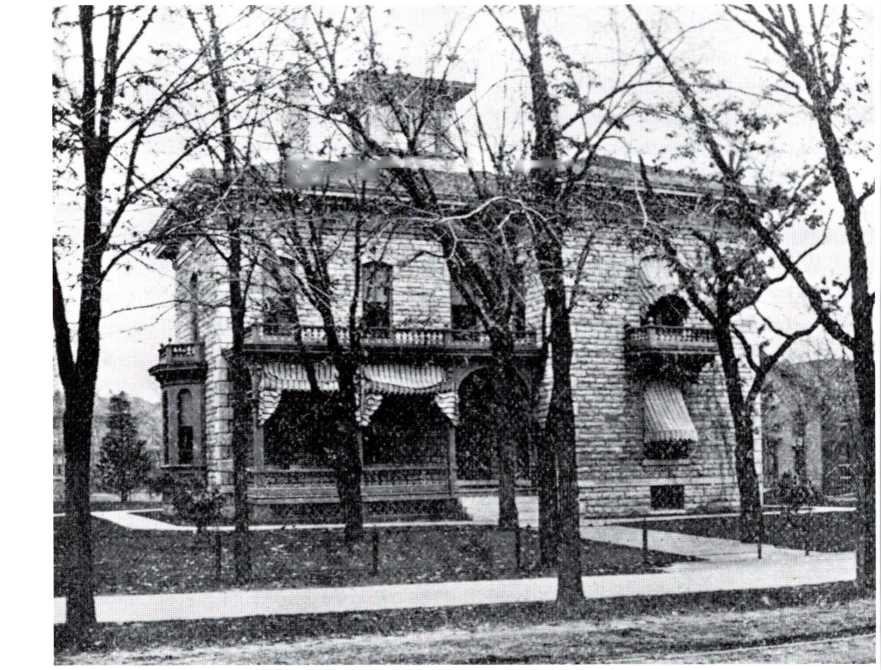

Sarah Harrison Knight’s residence after marriage was not far from her parents’ home (Illustration from John Wesley Hill, Twin City Methodism, 1895, collection of Minnesota Historical Society)

Sarah participated in church activities with her family and watched her parents, aunts, and uncles involve themselves and others in the church and Sunday School as they built the Methodist presence in Minneapolis.

The entire Harrison family was involved in fundraising for the church. During the Civil War, when land was needed to build what was to become the Centenary M.E. Church, Sarah’s aunt, Anna Harrison Goheen, led the women of the church in raising money to pay for it. Pledges ranged from 15 to 50 cents a month, with a goal of 100 dollars. After collecting for quite a while, Anna went to her banker brothers and took advantage of the gold advance, doubling their money.10

Sarah also learned from her aunt Anna how to work within groups to accomplish a higher goal. When a schism developed in the Centenary M.E. Church in 1875, the Harrison family was among those who helped establish the Hennepin Avenue M.E. Church. Anna took on the organization and operation of the Sunday School, with one children’s class and 13 adult classes. From the beginning, the importance of adequate training for the teachers was recognized. Evening sessions were typically scheduled once a month. When complaints were received after a particularly intense schedule, Anna said, “Remember you can make a crooked wall out of straight bricks,” implying that good Sunday School programs require more than good Christians.11 Sarah’s work amplified the work she observed in her activist family.

In 1870, Sarah Harrison married James Melvin Knight (born March 16, 1841, in Paris, Oxford County, Maine), son of Daniel and Abigail Evans Knight, who had arrived in Minneapolis in 1867 from Maine.12 The young couple moved to Stillwater, in Washington County, Minnesota, where Mel (as she called him) helped organize the public school system.13 He soon asked Sarah to fill in for a teacher who was ill, and with the books he provided, she taught for most of one school term. When the other teacher recovered, the class petitioned Superintendent Knight to let her continue to teach there.14 The Knights remained in Stillwater for three years, then returned to Minneapolis to establish a hardware business in partnership with others in the Harrison family. Their only child, Edith,15 was born November 1, 1877. Sarah was a mother of the times, keeping house and taking care of her daughter. In 1882, J. M. Knight contracted tuberculosis; he died in Minneapolis on August 5, 1883, leaving Sarah with a young child. Sarah didn’t have much time to grieve her loss. Life was further shattered when her beloved mother, Rebecca M. Green Harrison, died on February 13, 1884. Her father contracted typhomalarial fever the next year, on a trip through the South. He never fully recovered, and he died on October 27, 1887.16

Sarah must have been devastated. She transferred her church membership to the Hennepin Avenue M.E. Church from the Centenary M.E. Church, joining the rest of the Harrisons. She then took her daughter and traveled, drawing on her inheritance in an attempt to escape the pain of her personal losses. She carried her husband’s Bible and her Methodist hymnal with her as they visited Europe, the Holy Land, and even Imperial Russia. In London, on the evening of October 27, 1888, the anniversary of her father’s death, Sarah was preparing to say her evening prayers when the 58th chapter of Isaiah caught her eye: “Pour out thy soul to the hungry.” She returned to Minneapolis, determined to heed that message and devote her effort to the task.17

The upheaval in Sarah’s personal life and her new resolve paralleled the awakening of a social consciousness in the church. A tide of immigrants had swept into the American cities, including Minneapolis. Believing that America was a golden land of opportunity, they often were not prepared for the reality. Drunkenness, hunger, homelessness, and other social ills grew out of their poverty. In response to their problems, church members were encouraged to consider evangelism efforts as home mission work. According to the September 1913 Hospital and Home Messenger, “Deaconess work is a broader movement and offers a larger service to the church and humanity than most of us seem aware…It reaches out in every direction, where the heart of the Master goes and seeks to lift up the downtrodden and oppressed, correcting unwholesome moral and industrial conditions; teaches those in lower strata of society the truer meaning life, and offers comfort and aid to those who need the consolation of the gospel and of Christian sympathy.

“In the words of our discipline, the deaconess ‘is to minister to the poor, visit the sick, pray with the dying, care for the orphan, seek the wandering, comfort the sorrowing, save the sinning, and ever be ready to take up any other duty for which willing hands cannot otherwise be found.’” Deaconesses often found themselves visiting the poverty-stricken families of alcoholics to listen, offer support, and even help clean their houses. Several institutions were established to help prepare them for this work beyond the training provided by the communities in which they lived. The Chicago Training School for City, Home and Foreign Missions, established by Lucy Rider Meyer in 1885, had a considerable impact on developments in Minnesota.18

By 1888, the Hennepin Avenue Methodist congregation was sponsoring the Northwestern Deaconess Home of the Methodist Episcopal Church. The congregation installed Caroline F. Rotes (a graduate of the Chicago Training School) as superintendent, but the program faltered in March 1891.19 Sarah very soon determined to revive the deaconess movement, which she felt embodied the message from Isaiah, in Minneapolis. She had inherited from her father the family home,20 near the residence she shared with her immediate family. On August 12, 1891, she invited the leading figures of Twin Cities Methodism to the spacious home at Fourth Avenue and Eighth Street in Minneapolis to offer it as a residence for deaconesses; she also pledged her financial support. With that encouragement, the Rebecca M. Harrison Deaconess Home (named for her mother) was incorporated on the following day.21

The general purpose of the corporation was “to organize, promote and maintain the work of deaconesses as provided for by the discipline of the church … its plan of operations is to provide a home for such deaconesses, to give necessary instruction, maintenance and assistance to those who shall be engaged in such work, or preparing therefore, and so far as practicable to develop and maintain the work of such deaconesses in the various forms of Christian charity and benevolence.”22 The bylaws dictated that seven members of the home’s board be from the Hennepin Avenue M.E. Church (one was Sarah), and another four from other Minneapolis Methodist churches. Again, Caroline Rotes was named superintendent.

Although the deaconesses attracted hundreds of supporters, Sarah was not satisfied. She remembered the work she saw on her visits to hospitals in Europe and elsewhere. With the deaconesses, she took on a new challenge: health care for Minneapolis’s poor and indigent population. The timing was perfect. The three-year-old Minnesota College Hospital, a forerunner of the University of Minnesota’s hospital and medical school, was moving, and its building was available. On September 1, 1892, Sarah and the deaconesses opened Asbury Hospital, which Sarah named for her father.23 Sarah recruited Hamline University professor and fellow Hennepin Avenue Methodist Dr. Frederick Alanson Dunsmoor as the first chief of the medical staff. His reputation in surgery and gynecology brought other outstanding physicians to practice at Asbury.24

The first Asbury Hospital, at Sixth Street and Ninth Avenue South in Minneapolis (Photo courtesy of Methodist Hospital)

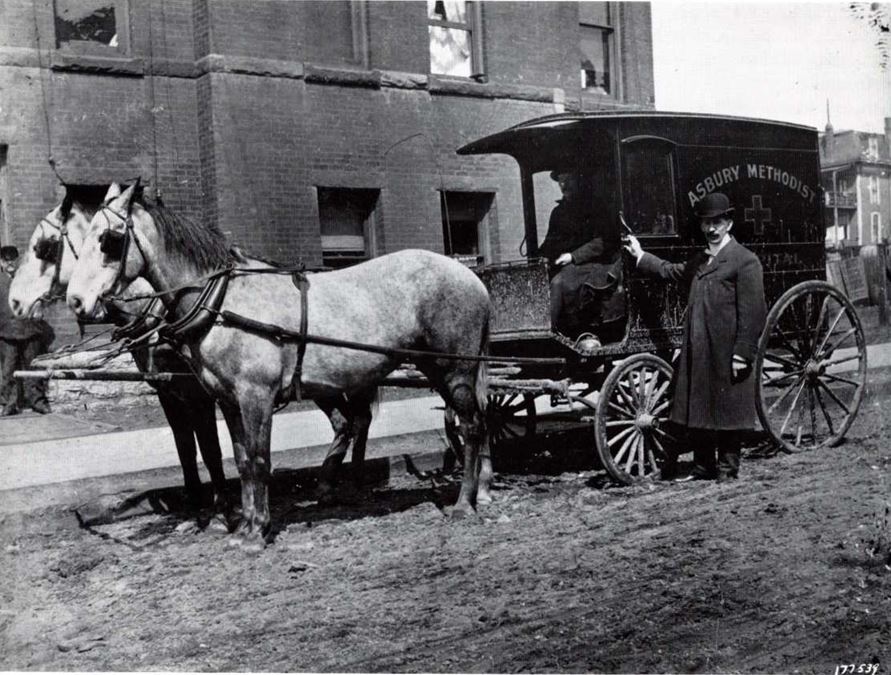

The Asbury Hospital Free Ambulance, an 1893 donation, carried patients to and from their homes, to other hospitals, or to the depot. (Photo courtesy of Methodist Hospital)

Sarah Harrison Knight donated land for a new hospital at the edge of Elliot Park, below in 1904. (L. D. Sweet photo, courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society)

Staffed by Minneapolis deaconesses, nine nurses, and Sarah as superintendent, the 34-bed hospital had a free dispensary for patients unable to pay for doctors and medicine. Sarah enlisted practical support from her church family: the Hennepin Avenue M.E. Sunday School contributed a free, horse-drawn ambulance to make the rounds of Minneapolis neighborhoods and bring patients to the hospital. A school of nursing was established shortly after the hospital was opened, with nine women in the first class. The Hospital and Home Messenger informed Minnesota Methodists of this work and of the food, blankets, other supplies, and cash donations received from Methodists all over the state.

A fire in 1895 almost destroyed the hospital and Sarah’s dream. But within three days, the decision was made to rehabilitate the existing building and reopen the hospital. With the patients transferred to St. Barnabas Hospital, reconstruction took four months. Again Sarah was not satisfied with the work. She wanted to build a new and larger hospital. To make the idea more appealing, she donated a site for it several blocks away, on the edge of Elliot Park. Fundraising began in all Methodist churches in Minneapolis, and the Hennepin Avenue Methodist Church pledged more than one-third of the $120,000 estimated cost. Sarah’s mother-in-law removed the first shovelful of dirt at the groundbreaking in 1900. The facility finally opened in 1906. 25

As involved as she was in the daily activities of her hospital, Sarah continued to serve in church offices as well, including the Sunday School board. She still performed the duties of a mother, encouraging her daughter Edith in her singing, dancing and artistic talents and even building her a stage in the family home. Edith, too, brought her talents to the use of the church, serving as playwright and director of several dramatic events for the Hennepin Avenue M.E. Church.

Many of Sarah’s friends, family and fellow church members were recruited to support Asbury Hospital and the Rebecca M. Harrison Deaconess Home. In 1915 she convinced her friend Harriet Arnold Tourtellotte, the widow of Dr. Joseph Tourtellotte, to donate $125,000 for the construction of the Tourtellotte Memorial Deaconess Home near the new Asbury Hospital. This building provided a home for the more than 60 deaconesses then working at the hospital. 26 (Joseph was a lifelong Baptist who had been on the staff at Asbury.)

Sarah’s aunt Anna, her niece Grace Harrison Ramsey, and the Longfellows, as well as Cyrus Morehouse, Emma Benton, Levi Stewart, J. J. Hill, Caleb Door, and Earle Brown, all prominent and wealthy citizens, became substantial contributors to Asbury Hospital and the deaconess home. In addition to her more than 30 years of leadership, Sarah personally gave more than $50,000 to Asbury Hospital (her colleagues conservatively estimated). A 1903 report to the board of directors noted: “The books do not distinguish the many times when this Princess of Givers, coming into the hospital and laying down a check—often for several hundred dollars—would say, ‘here is a little of the Lord’s money. If you have to put it down, say from a friend,’ or ‘take this patient in and send me the bill and don’t put it down to charity.’ Nor does it include $500 given for each of two years which supported two visiting deaconesses in small churches for that time.”27 years of her life here, she frequently said she would Sarah’s successor, Lydia Miller, eulogized her on the occasion of the hospital’s 60th anniversary in 1952: “During the last few like to carry on until the hospital was debt free.” And, in fact, Asbury Methodist Hospital was virtually debt free in 1927, the year before Sarah’s death.

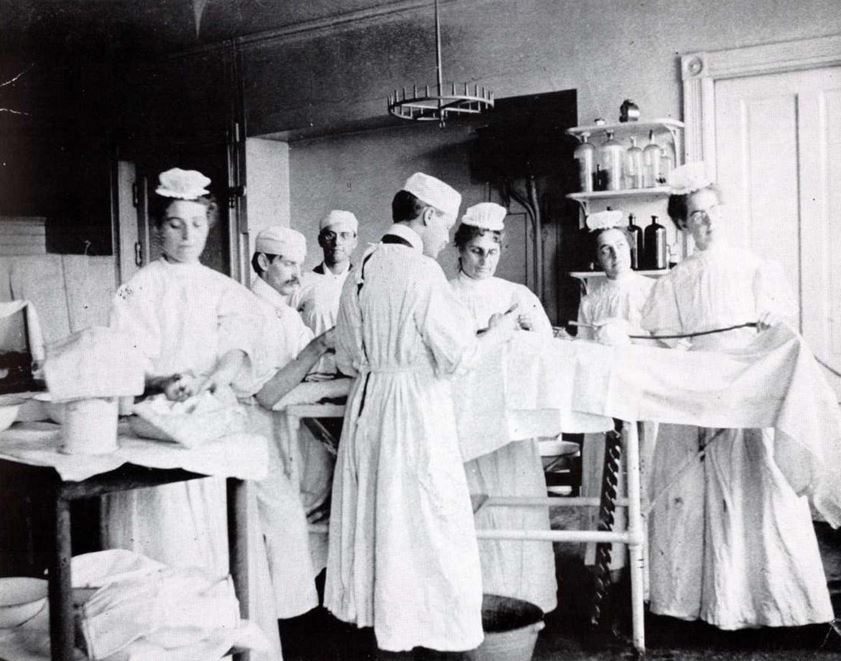

But Sarah’s legacy to the hospital and the community was more than financial—it was strong leadership. Abbott G. Fletcher, longtime general counsel and treasurer of Asbury Hospital, said in 1938: “It is impossible to give a financial history of Asbury Hospital without reference to Sarah H. Knight. She it was who had the original dream and throughout the years she struggled heroically to make the dream a reality. Always, before any of the forward steps were taken, the minutes show that for two, three or more years, Mrs. Knight had recommended the advance.”28 Perhaps a more subtle result of Sarah’s commitment and talent at Asbury Hospital was the early acceptance of female physicians and other women in leadership positions. Sarah herself took her role as superintendent of the hospital seriously, and she went to the hospital every day. She also recruited and gave positions of responsibility to other women.

After Caroline Rotes, Sybil Palmer (another graduate of the Chicago Training School) served as superintendent of deaconesses, from 1894 to 1922. Dr. Mary S. Whetstone was only the second woman doctor in Minneapolis when she arrived in 1890. She was part of the pediatric medical staff at the Asbury Hospital’s opening in 1892. Dr. Eleanor Jane Hill was named to the Asbury staff in 1907. Sarah herself was succeeded as the hospital superintendent by another woman, Lydia Miller.

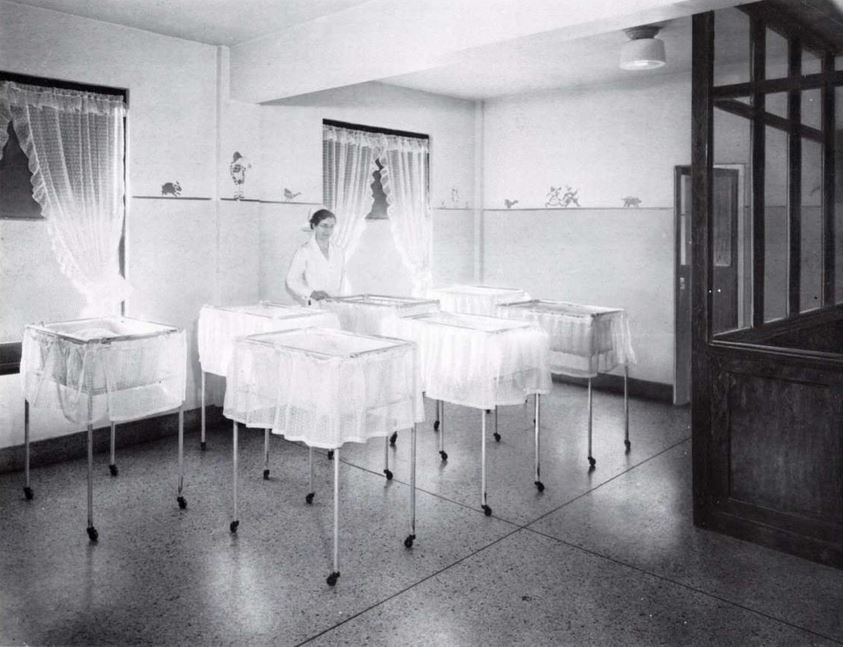

A nurse watched over infants in the Asbury Hospital nursery in 1940. (Photo courtesy of Methodist Hospital)

The Asbury staff performed surgery in the late 1890s. (Photo courtesy of Methodist Hospital)

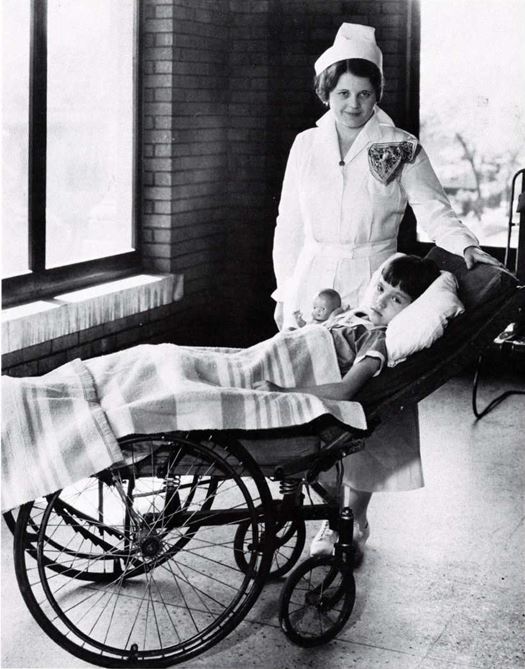

Nurse Lily Myrold (later Swanson) posed with a young patient at Asbury Hospital in about 1940. (Photo courtesy of Methodist Hospital)

Sarah died on April 4, 1928, from complications of a fall. The next month, the hospital board passed the following resolution: “Whereas, from the beginning of her great and sacred task she ventured her strong faith, courage and abilities, together with her private fortune, in the great enterprise which was fostered by an often repeated passion for an institution that would embody the spirit and perform the service of Christ, and which stands today, the creation of her genius and the embodiment of her policy and sterling character; and “Whereas, the favorable financial condition of the property, which consists of two hospitals and the Home, is the result of her Faith in God as well as her fine business sagacity, executive ability and rare spirit of initiative; and “Whereas, during the busy years of her long life, many other worthy and humanitarian efforts in this city and elsewhere were the recipients of her kindly heart, suggestive mind and open purse; “Therefore, Be it Resolved, that we hereby bear witness to her Christ like spirit, her faith in God, and her indefatigable labors for the suffering and needy for the Church of Christ, and to her sacrificial efforts in many directions; and “Be It further Resolved, that we hereby pledge ourselves as members of this Board to give our best interests to the institutions she has left in our charge, which hold such a commanding place in this city and state, by endeavoring to advance toward the high Christian ideals she so earnestly strove to realize in all her labors, and “Be it still further resolved, that we hereby express our deepest sympathy to her daughter, Mrs. George K. Belden, and to her family in their loss of such a Christian mother, and by these resolutions express to them the highest esteem in which she was held by us; and “Finally, be it resolved that a copy of these resolutions be spread upon our minutes and that another copy, inscribed in Old English and suitably framed, be presented to Mrs. Belden and family.”

After her 36 years at the head of the Hospital, Sarah Harrison Knight was finally satisfied. In her will, dated February 24, 1926, she mentioned her great interest in both Asbury Hospital and the Deaconess movement of the M.E. Church. She made no provisions for either organization, for the reason that “I feel I have given them all that I was able to contribute of my time, labor and large sums of money. I did this so that I could see for myself just how the money would be used, and I have been much pleased with the manner in which the Boards of both said organizations have managed and expended such funds.”29 She left her estate to her daughter and granddaughters.

Though Sarah was a major influence in both health care in Minneapolis and in the church, her personal story and accomplishments are not chronicled in the various published histories of Minneapolis or of the churches. Sarah joined the Hennepin Avenue Methodist Church in 1888, before the founding of the Rebecca M. Harrison Deaconess Home or of Asbury Hospital. She is not mentioned in connection with either event in their centennial histories.

Asbury Hospital was the newest hospital in Minneapolis when Isaac Atwater wrote his history of the city in 1893. Not having her foresight and unable to understand the value of her commitment, Atwater wrote: “After careful consideration of the [Dunsmoor] plan, Mrs. Knight concurred in it and donated $10,000 toward its inauguration. This sum, with what was already on hand in donations of stock from the several holders, was found to be sufficient to accomplish the transformation of the Minnesota Hospital College into the Asbury Methodist Hospital.”30

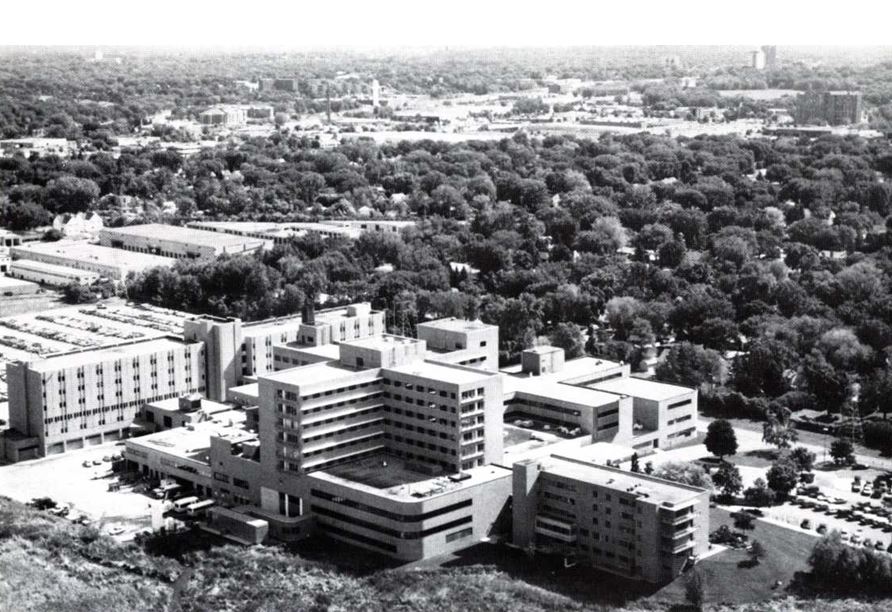

He did not value the work she did in establishing the Rebecca M. Harrison Deaconess Home or the work she was doing within the Hennepin Avenue M.E. congregation and among her social groups to support the hospital and deaconess home. The History of Minneapolis published in 1923 includes biographies of her father (who died in 1887), her husband (who died in 1883), and her son-in-law, containing information most likely collected from Sarah herself. There is no sketch of Sarah, though she is mentioned in that history as James’s wife. Neither do her obituaries provide much detail about her life or accomplishments beyond comments on her financial contributions.31 The result of her work and its caring for others was important to Sarah; the recognition that would accompany similar efforts by a male was not given her. In this silence, today’s women lose a powerful role model. She fulfilled the socially acceptable role of mother and grandmother to her daughter and grandchildren; she helped bring health care to the needy. She accepted the challenge of the Christian life as few others did, to go forward and assume the responsibilities of a “broader and grander work.” Methodist Hospital, the fruit of the small hospital founded by Sarah Harrison Knight, celebrated its centennial in 1992. By that time the 426-bed acute care hospital employed 2,500 (including 800 on a medical staff representing 57 specialties); it is recognized today as an area leader in cancer care, neurology, and rehabilitation medicine, cardiovascular services, senior care, emergency medical, and maternity care. Sarah would not be surprised.

Asbury Hospital temporarily leased its facilities to U.S. Veterans Hospital No. 68 to retire its debt in the 1920s. The entire staff turned out for this photograph in 1922. (Photo courtesy of Methodist Hospital)

Sarah Harrison Knight probably would not be surprised at the progress that Methodist Hospital, (foreground), the successor to the hospital she founded, has made in caring for patients in the area it serves. (Photo courtesy of Methodist Hospital)

References

- Information about the growth of Asbury Hospital and its transition into Methodist Hospital is from a booklet and a book celebrating the centennial of Methodist Hospital. Both were written by Bill Beck and both are entitled A Tradition of Caring. The 30-page booklet was released in December 1991, and the book (St. Louis Park, Minneosta: Methodist Hospital) in 1992. The author is grateful for the opportunity to read the manuscript before its release and to use materials from the hospital’s archives.

- During an interview in 1895 on the occasion of the twentieth anniversary of the Hennepin Avenue Methodist Episcopal Church (Minneapolis) on the current role and future of the church. Taken from Richard Bryden Dunsworth, ed., A Centennial History of Hennepin Avenue United Methodist Church 1875-1975 (Minneapolis: The Church, 1975), 142.

- Information on the development of the Methodist Church in this area can be found in Joseph Calvin Evers, The History of the Southern Illinois Conference: The Methodist Church (Nashville: The Parthenon Press, 1964); and Rev. J. D. Gillham, “The Methodist Episcopal Church,” in History of St. Clair County, Illinois (Philadelphia: Brink, McDonough, 1881).

- As with most pioneering families, the Harrisons may have had more children who were born and died between census years and for whom no vital records are available. Nine children can be documented through U.S. Census and local history narratives.

- A well-known minister who also came to Minnesota, Reverend Peter Akers married Ann Goheen on May 12, 1846, also in St. Clair County. Akers served several terms as president of McKendree College and preached often in the area.

- Isaac Atwater, ed., History of the City of Minneapolis (New York: Munsell, 1893), 493.

- Ibid.

- Isaac Atwater, ed., History of the City of Minneapolis (New York: Munsell, 1893), 493.

- Atwater, ed., History of the City of Minneapolis, 493.

- Similar stories are included in several church histories from congregations in which the Harrisons played a part. The Wesley Church, located in downtown Minneapolis, is the successor of the Centenary congregation. See History of Wesley Church: The First 125 Years and The Mother Church of Minneapolis Methodism (both Minneapolis: Wesley United Methodist Church, 1977); and Dunsworth, ed., A Centennial History of Hennepin Avenue United Methodist Church 1875-1975.

- Dunsworth, ed., A Centennial History of Hennepin Avenue United Methodist Church 1875-1975, 12.

- Their marriage license was issued in Hennepin County onjune 13, 1870

- Marion Shutter, History of Minneapolis, vol. 2 (Chicago and Minneapolis: S. T. Clarke Publishing Company, 1923), 49-50.

- Beck, A Tradition of Caring, 18.

- Edith married George Kimball Belden, son of Judge Henry and Carrie (Kimball) Belden, and they had four daughters. She died on August 26, 1964, in North Hollywood, California, and was buried with her husband near her parents at Lakewood Cemetery in Minneapolis. George Belden died on May 20, 1953.

16. Atwater, ed., History of the City of Minneapolis, 495.

17. Beck, A Tradition of Caring, 3.

18. Mary Agnes Dougherty, “The Social Gospel According to Phoebe,” from Hilah F. Thomas and Rosemary Skinner Keller, eds., Women in New Worlds (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1981), 202-03.

19. Thelma Ballinger Boeder, “Overview of Deaconess Work in the Minnesota Annual Conference, 1889-1986,” presented to the United Methodist Women of the Richfield United Methodist Church in Minneapolis, March 6, 1986.

20. Hennepin County Probate File #2531.

21. Beck, A Tradition of Caring, 11.

22. N. Farnham to Dr. Dunsmoor, on organization of deaconess homes, Methodist Hospital Archives.

23. Beck, A Tradition of Caring,

24. I. Holcombe and William H. Bingham, eds., Compendium of History and Biography of Minneapolis and Hennepin County, Minnesota (Chicago: Henry Taylor & Company, 1914).

25. The Asbury Hospital board reported to its employees in 1905: “Hospitals in the main are money losers. This is the chief reason why physicians who are ambitious to have a hospital for local needs are anxious to have a church or the community to become responsible for the finances of the institution.”

26. Beck, A Tradition of Caring,

27. , 13.

28. , 13.

29. Hennepin County Probate file #35160.

30. Atwater, ed., History of the City of Minneapolis,

31. Obituaries appeared in both the Minneapolis Tribune and Paul Dispatch on April 5, 1928.

Mary Hawker Bakeman is a genealogist and former board member and chair of the publications committee for the Minnesota Genealogical Society. She is the co-owner of Park Genealogical Books and the editor of the Minnesota Genealogical Journal. She has written and edited numerous historical articles, indexes, and guides.